Over the past few years, as discussions around mental health and emotional labor have broadened and deepened, so, too, have rebuttals against it.

Taking issue with the language of emotional labor, which takes note of how people of color in world societies are weighed down by systems of oppression and yet still expected to over-perform, are those who don't have to do it (that is, white people, especially those protected and upheld by POC-opposing systems of privilege.)

But the heavy lifting of emotional labor, of constantly correcting the ills of racism, homophobia, transphobia, classism, sexism, and all other forms of discrimination, is exhausting. And being led to believe that, as a marginalized person in any society, it's your duty to right the wrongs of a system determined to fail you, means emotional labor is also traumatizing. Each attempt to make the world a little safer can be like unearthing ancestral wounds that have never fully healed. If you're white and reading this, ask your POC friends, assuming you have more than one. In America, people of color know this particular exhaustion intimately, and come into contact with it on a daily basis. There is often little room or respite away from it.

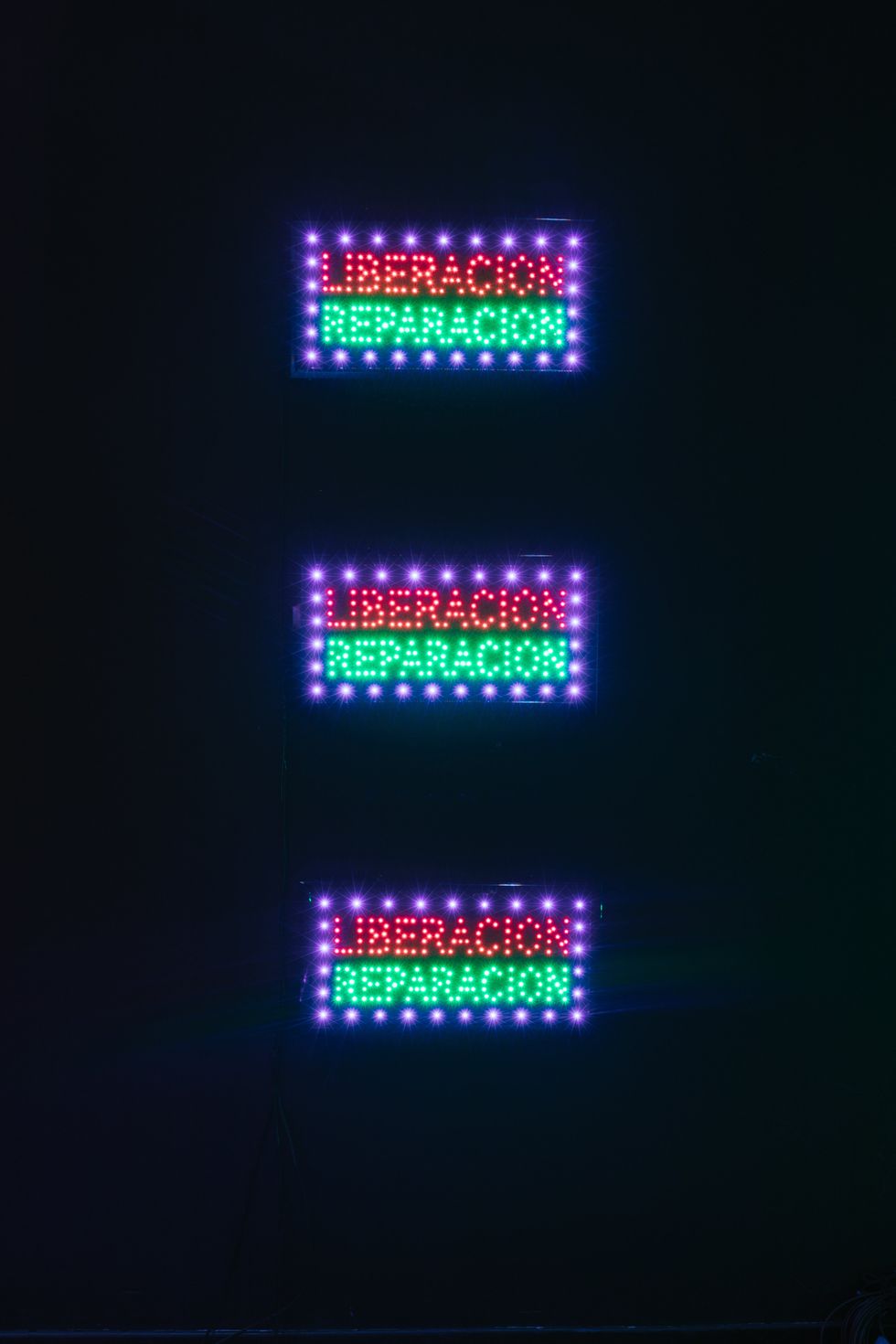

Photo: Da Ping Luo

Because vacations are expensive and not always accessible, enter multi-media artists and activists niv Acosta and Fannie Sosa (who prefers to be called Sosa), who, after realizing the toll their own labor was taking on them and their loved ones while in Berlin, decided to create a luxurious, comfortable space in which people of color could just rest. "Ultimately, it's really the white man's worst nightmare to have a fully rested negro who is fully self-possessed," Acosta tells PAPER. "[In order] to literally have the legendary clapback which we all need, we need rest."

Good, quality rest is not a luxury commonly afforded to people of color, as recent studies have shown that the distribution of rest is determined by race and class, with people of color regularly getting less hours of sleep a night than their typically wealthier white counterparts. Acosta and Sosa are addressing this phenomenon with their current exhibition, called "Black Power Naps," which so far they've presented in Madrid during a five-month residency. In New York, Black Power Naps has been up since January 9, with two "activating" performances by Choir of the Slain (part X), and until January 31 at Performance Space New York. The exhibition's genesis is predicated on the belief that lack of sleep for people of color is also related to factors that other studies support, such as socio-economic status, lower education levels, and even being unmarried is linked to poorer sleep habits.

Photo: Da Ping Luo

Additionally, the artists see it as a continued form of state sanctioned punishment born from the ongoing legacy of slavery, and if you take into account American texts from the antebellum South, this is true: it was common knowledge that slaves worked in harsh conditions on plantations — by force, threat of humiliation, and to receive basic necessities of food, water, shelter, and clothing — from "can see in the daytime until can't see at night." And still, the constant work hustle continues. In a press release detailing Black Power Naps, it is noted that "our culture has required that people of color present themselves as extraordinary performers, athletes, or entertainers in order to exist in the public realm."

So to address the need to rest, and thus, restore and take back the power of POC existence, Black Power Naps is outfitted with six approaches within the interactive installation to promote a restful body. According to a press releasing detailing the space: there is a circular bed with silk sheets, cushions, and a canopy called the Black Power Base; the Polycrastination Station hosts a suspended vanity and illuminated ceiling mirror, inviting visitors to lay down in order to gaze at one's own reflection; the Atlantic Reconciliation Station features a body-adjusting water bed; the Oxygenation Swing is lined with floating hammocks and silent fans designed for better air circulation, which promotes better sleep; the Pelvic Floor trampoline is surrounded by vibrating bass subwoofers; and the Black Bean Bed is a pool filled with black beans, weighted blankets and cushions, with hanging fresh herbs and a space canopy blanket. That space was created using techniques said to soothe various symptoms of anxiety.

Doesn't that all sound so nice? PAPER caught up with Acosta and Sosa to discuss why rest for people of color is radical, the barriers they've encountered, and expansion of the project.

PAPER: How did this project first come about?

Acosta: It was born basically in a room full of Negroes in Berlin. I was facilitating a two-day structural racism training for cultural producers, and so at the end of two days we had done so much work of like, unpacking structural racism and the context and the history and pedagogy, all this stuff, and we were exhausted. So, somebody was like, "I wish we could go to my house right now and just have a cuddle party." I just looked around and I said, "Black power naps," really loud. Then I called Sosa, I think that same day, and told them about the idea. From there basically, Sosa and I have been envisioning this as a space, as a conversation, as a methodology. As many things. But yeah, the physical installation and incarnation of this work started four years ago.

Sosa: It just was born out of communicating a lot around what institutions of culture in Europe were making us exhausted — from microaggressions to macro things, a lot of them run with the expectation that you're supposed to be super grateful to even be there in the first place. So we thought, Let's take a nap on these bitches, how can we make these bitches pay for our napping?

What were some difficulties that you both faced when you decided to actually put things in motion?

Acosta: So much of how cultural work intersects with reality, it's often the white institutions' job to economize struggle, if that makes sense. If Black folks are really at the frontiers of creating content and pedagogies and vernacular, then we're certainly out here on the frontier of literally so many things when we're talking about putting the words "Black" and "power" in one sentence. Even when the context is sleep, often we're met with a lot of like, "Well, where's the empirical data? I need proof that this needs to be a part of the reparations ask, I need this to also be benefiting my institution." It is often the task of a Black artist to be engaging the community, whereas whiter artists are not necessarily asked to do this. So we're constantly faced with this conundrum to activate the local Black community, and we travel a lot. We go to different places. I'm from New York City, Sosa's from Buenos Aires. A lot of the cities we're in, we don't know anybody. So paired with a history of our own individual practices and what the white institution asks of us to engage the community, and now with this project where we're saying, "Now you have to open your doors for free, essentially pay Black people to sleep, and be OK with it, and also create a permanence." Right? Because we're not just there for one week, we're there for three, four weeks. In Madrid we were there for six weeks. I think the greatest challenge is honestly the vernacular, it's the words. When you say "Black Power Naps" to any white institutional leader, they're like, "Oookay." You know? In terms of press and all of that, I'll be really real, we're struggling to have people even publish about the work.

Choir of the Slain (part X) performs at Black Power Naps.

Photo: Maria Baranova

It's as if there’s something about the work that makes people uncomfortable and touches a nerve, where they feel like they can't approach it.

Acosta: I mean, ultimately, it's really the white man's worst nightmare to have a fully rested Negro who is fully self-possessed, to literally have the legendary clapback which we all need, and in order to do that, we need rest. We need that patience and rest. That's really at the core of this project. Beyond the issues of being able to present this work or having people just not want to align themselves with something so radical, in a sense, is so a part of the conversation as well.

"Quality sleep is really only given to white, rich people." —niv Acosta

Have you gotten heat since launching this? And can you talk about the racialized divide between the quality of sleep for Black people and POC versus white people?

Acosta: There's literally commentary on the VICE post, white men are like, "You'll never replace us." That's literally verbatim one commenter on the post on VICE. People are like, "I'm mad that these devices are geared towards only one race, white people need rest as well." Meanwhile, of course, at the seat of our research is all of this empirical data about how sleep is literally only important to the wealthy. Quality sleep is really only given to white, rich people. We're talking about sleep technologies. We're living in hyper-capitalism, right, which is hyper-toxic masc. It is really decentralizing the body. So we're talking about people who are perfecting sleep, people who are training on how to go in and out of REM cycles like a pro. We're talking about the President of the United States, these people literally teach themselves how to go in and out of REM within a half hour so that they can just take naps throughout the day and still be running a country. That is also a level of access and privilege that Black folks need to. In order to engage with the capitalist society that we're in, we need to be able to also engage with the technologies that are developing to essentially help us survive this shit, which is to be able to sleep well and live longer lives.

Choir of the Slain (part X) performs at Black Power Naps.

Photo: Maria Baranova

What about the successes so far?

Sosa: The response that we've gotten from the community is amazing, I'm actually surprised. The events were sold out within days. We have an event on Saturday, we put out the tickets yesterday. There's only four left [at press time]. Clearly it's popping, but again [as niv was saying], somehow that isn't reflected by the press, you know? And I feel like when we did it in Madrid, it was like a similar feel. We ended up having to go out to our social media saying, "Yo, we need some more press about this, what's going on?"

So would you love it if people did Black Power Naps in their city?

Acosta: Ultimately, yes. It would be amazing to be able to translate the tools and the technology that we're developing not just these objects that we have here, but actually develop new and more streamlined sleeping technologies. We're talking to people in Toronto and Montreal right now, trying to keep it on this side, just be opportunistic about it being over here.

Sosa: Well, honey, we need help with that. To be really real, the full tea is that an installation like this is actually quite expensive and we do exist to make it free, and so as of now, we haven't any plans and we're trying to change that. But we'd love to bring it back to Europe next. Bring it back, actually.

What other events do you have coming while the exhibition is still up?

Sosa: A pajama party. We're also thinking about meetings, organizing. All of that is kind of a civic space to like, gather and scheme and scam. We're going to have a birthday party and a play party.

Acosta: We have a dinner like, opulence and delicacies with this really awesome chef who's going to make like sleep-themed foods. I'm going to be DJing a set from bed on Saturday. We're also doing two screenings, one of Shakedown, Leilah Weinraub's film, and Happy Birthday, Marsha! by Sasha Wortzel and Tourmaline Gossett. And then we're doing a DJ set after that, and it's my little baby cousin's birthday also, so we're going to have a Hulk cake. I'm so excited, it's like a dream bedroom, to be honest. To be able to throw a rager in your dream bedroom is actually like, goals. Goals as fuck.

For more info on Black Power Naps, follow niv Acosta at @nivacosta, and follow Sosa at @fanniesosalove.

Lead image via Instagram