LGBTQ

Coming Out Is Hard, Even When It's Not

A personal essay by Khalid El Khatib on cultures of closets and cynicism, and how "coming out" is a never-ending process.

Text By Khalid El Khatib

20 June 2017

A personal essay by Khalid El Khatib on cultures of closets and cynicism, and how "coming out" is a never-ending process.

In Tokyo, the best sushi restaurants are unassuming. They're either unmarked—tucked into subway stations and back alleys—or they don't accept reservations in English, let alone from tourists. To eat well, really well, you have to know locals.

So my first and recent work trip to Japan allotted the best of both worlds: a couple of free days on the weekend to go out and explore, and the luxury of having local colleagues to take me to an authentic sushi dinner.

We sat at the counter of an unassuming restaurant tucked between a strip mall and a gas station and down a flight of stairs.

Early conversation focused on work.

"What did you do before advertising?" My female Japanese colleague asked from a few seats away.

As she finished asking, the chef put a plate in front of me with a shrimp, head-on, a small squid, and another piece of seafood I didn't recognize.

"Lots of things," I tried to piece together a thoughtful answer while using my chopsticks to maneuver off the shrimp's head. "Mostly advertising or communications-focused work. A brief stint in real estate—before the market crashed in 2007."

And as the shrimp's head fell to my plate, "Before that retail, lots of retail."

My colleague's eyes lit up.

"Where? Tell me where! I love to shop."

"Well, in high school I worked at shoe store in my hometown. In college, I sold shoes at Nordstrom during a couple of summers and over the holidays." She clapped her hands together.

"And when I first moved to New York, while I was figuring out what I wanted to do, I worked at the Ralph Lauren in Bloomingdale's."

She asked how it was. I explained that the pay (entirely commission-based) was pretty good, but I ended up losing most of it to my employee discount.

"What was the discount?" Her level of excitement indicated I might still have access to it.

"Like twenty or thirty percent."

"Did you use that fact on all the girls? To get dates."

It wasn't uncommon in Asia for people to think I was straight—mostly superficially, girls dressed as maids blowing kisses to lure me into a café, hotel attendees assuming a female colleague might be my wife. To experience the assumption by someone I'd spent the whole day with was jarring.

"Dates? Yeah," I smiled at her.

I smiled to the colleague sitting next to me, who's from China, and I've become close with over the past couple of years. She smiled back, a little quizzically, her eyes asking why I hadn't clarified my response.

I lifted the shrimp to my mouth. I swallowed.

Alone in my hotel room later that night I wondered why I didn't say anything, and I thought to moments recent and not so recent, but all after I came out, where I either hesitated, dodged, or misled a stranger about my sexuality.

Years ago, in my early twenties, I spoke to teenagers at the Iowa high school I graduated from about writing. I was vague about the outlets I wrote for—mostly gay men's magazines. My talk was followed by a Q&A. Did I get to meet any celebrities? Mostly drag queens and male models, I didn't answer.

Last Christmas, I bumped into a neighbor I hadn't seen in two decades at the grocery store. His son was in my Boy Scout troop. He shared that his son was expecting a second child. Was I married? Did I have a kid? No? Why not?

My cab driver on a two-hour drive back from JFK in traffic, after a trip to Miami: Man, he shook his head, the girls there are beautiful—those Miami tits. How many did you go home with? None. I put my headphones on.

These stories are a wild juxtaposition to my every day life in New York: writing articles like this, wearing cut-off tees, dating men…

A month after Asia, I was in Los Angeles and grabbed a drink with my ex-boyfriend, Scott. I wore a periwinkle t-shirt and faded skinny jeans; he wore a moth-eaten boat neck t-shirt. The roof we met on overlooked half of LA, and while I angled to take a pic of the view and a waiter poured our rose, Scott realized the handsome waiter was his friend's ex. In that moment, we couldn't have been gayer.

After the waiter walked away, as we glowed in gayness, I mentioned to Scott that I might be writing this piece, to get his take on it.

"I think about this a lot. We're sort of conditioned to be uncomfortable with being out." Scott came out around the same time as me, gradually, starting his late teens. "We spent so long denying it—to other people and ourselves. We grew up forming these elaborates ruses like girlfriends, or playing high school football. It's weird, but also not weird that there's a pit in your stomach—no matter how small—through so many 'coming out conversations' today."

A few weeks later, Scott texted me from a business trip to a satellite office of the start-up he works at: Meeting all these people in the office here, I recognize I come out so much easier to the women than the men. That lingering closet instinct thing.

It's true. My primary care doctor is gay. When he's not in, I'm made to see a covering physician and if anything remotely related to my sexuality comes up, I gulp. I get my haircut by straight guy and it was at least three months (and four haircuts) before the dating conversations mentioned dudes. And then there's the pervasive issue of the overly chatty Uber drivers who ask more questions about my dating life than my mom.

I wonder, maybe this sense of discomfort is a daddy issue—being gay is chocked full of them.

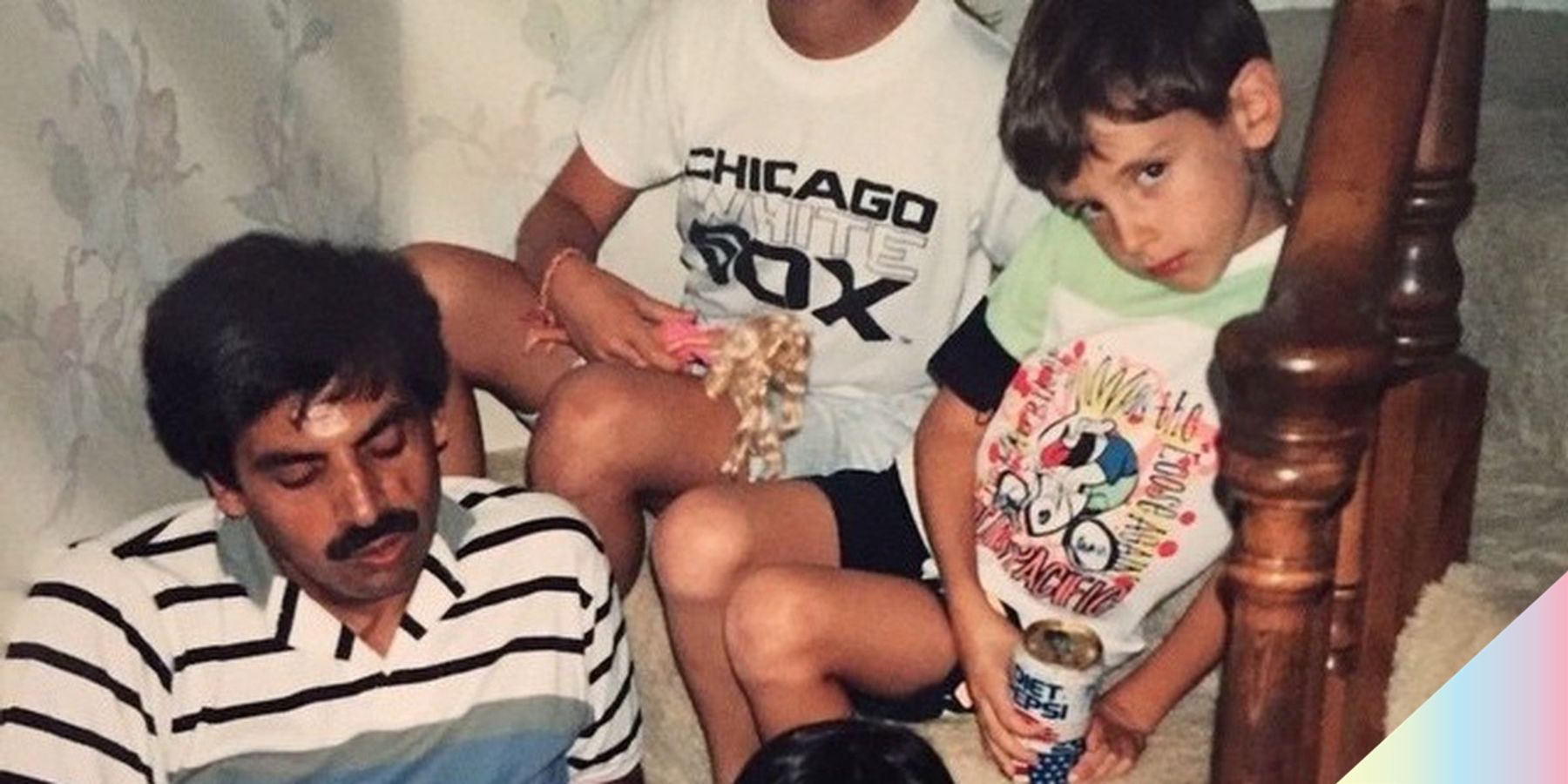

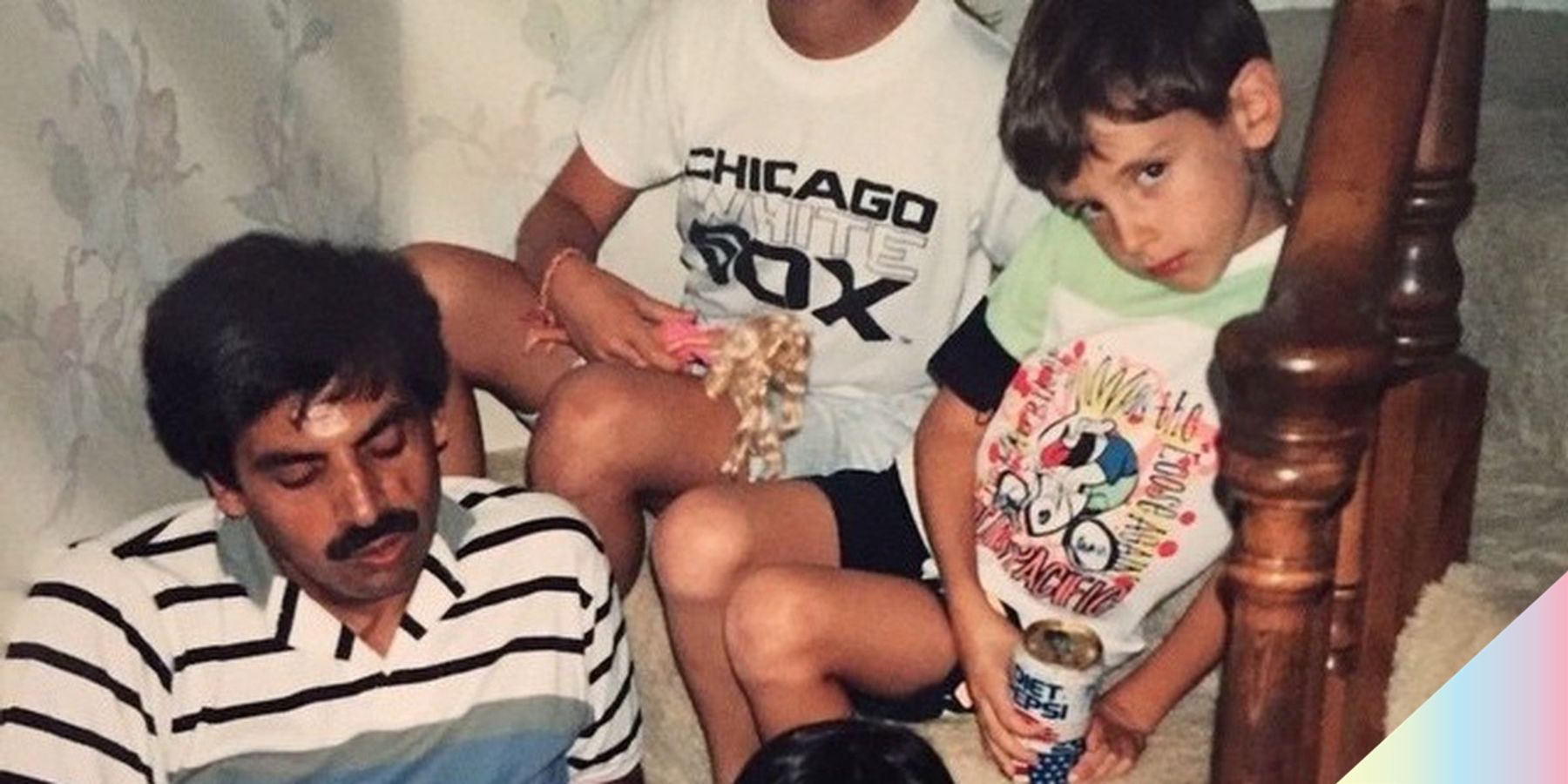

I waited to tell my dad that I was gay. I came out to friends and family when I was nineteen. I told him when I was twenty-seven.

My reason for waiting was twofold: first, and most simply, it was hard. He was born in the Middle East and he's a devout Muslim. I knew my coming out to him would disappoint him and worried, at worst, he'd disown me. But it was also an issue of maturity. I wanted to wait until I was old enough to empathize with his (likely negative) reaction to my sexuality. That's a difficult thing to articulate, so when people ask why I waited to tell him, I typically respond with, "It's complicated."

I've come out hundreds of times. I'm still coming out today—to colleagues, to drivers, to vendors, and to people as seemingly inconsequential as whomever you're seated next to on an airplane. While each conversation falls on a difficulty spectrum and most are easy, no single conversation is without nuance.

Reflecting on how hard it can be for me to "come out," and how odd it is for a thirty-something living in New York's West Village to struggle, I'm less fixated on the underlying psychology as I am by how often I diminish or belittle the significance of other people coming out.

Just last week I gchatted a friend to ask about a guy he'd been on one or two dates with.

Me: will you see him again?

Joey: no, not gonna work. he's like a late bloomer—late comer-outer. smart and funny but not dateable

Me: oh yeah. those people are always a little off.

It's no secret that casual bitchiness can come easy to many of us gays, but too often other LGBTQ people are the targets.

I went to a pretty liberal university for undergrad in the early- to mid-2000s. I rarely, if ever, felt discriminated for being gay (though there weren't many of us—at least not many who were out). In the one or two years after we graduated, an avalanche of guys we went to school with came out. Instead of respecting that it's a process, that it's not easy no matter the circumstances, my friends and I treated it as a mystery akin to that of The Virgin Suicides: what single factor forced all of them to wait?

These anecdotes are illustrative of a larger trend: there is a level of cynicism in the community around the burden of coming out. Take well-intentioned efforts that nonprofits like HRC and the Trevor Project make to encourage us to recognize National Coming Out Day. They get brands like Macy's and MetLife to tweet their support, and instead of recognizing how far corporate America's come, gay Twitter too often devolves into a debate about the efficacy of the stock photo of a rainbow they used in their tweet.

When a celebrity like Colton Haynes comes out, we too often focus on why he didn't come out sooner, how obvious it's always been that he was gay, and the language, photos, media outlets, and social networks he leveraged to announce being out. I'm not necessarily suggesting we blindly celebrate this sort of celebrity coming out, but to criticize them can place even more pressure on those who deeply closeted; it paints our community as unwelcoming and plays into stereotypes.

The reality is incredible progress has been made—gay marriage is the law of the land and corporations are more gay-friendly than ever. It also looks like we have momentum; young people are more accepting and gayer (a new study says 20% of millennials identify as LGBTQ) than any generation before them.

But progress can be dangerous when instead of catalyzing more progress it makes people comfortable. It can trick us into looking past the young people in rural communities who have never met an LGBTQ person; it can make us oblivious to terrified young (and old) people in countries like India, Iran, and Singapore where being gay is stigmatized or worse, criminalized.

Ever since the 2016 presidential election, there's been a growing movement to reject political correctness. About a week ago, when Pride month kicked off, I saw pockets on social media where LGBTQ "allies" were alleging there was no longer a stigma towards gay people, and therefore no longer a need for a month-long Pride.

The recent rise in hate crimes towards minorities, from Muslims and Jews to African-Americans and Mexicans (all populations that have grown in the U.S. in recent decades), is proof that representation and visibility has little to do with acceptance.

So if you're out, continue to be out but also revel a bit in the discomfort of brief—hopefully infrequent—moments you're in. They're a good reminder that we can't rest until everyone who is gay can be casual about being gay.