NSFW

Pot Is Hot: A Look Back At Our March 1993 Weed Issue

by David Hershkovits and Carlo McCormick / photos by Haim Ariav

20 April 2017

Happy 4/20, y'all! While state laws legalizing medicinal marijuana -- not to mention recreational marijuana -- are, in some cases, a relatively recent phenomenon, PAPER's been pro-pot legalization for decades. As far back as March 1993, we dedicated our cover story to an exploration of the growing legalization movement. Back then, we took a look at the diverse constituencies -- "rockers, rappers, Dead Heads environmentalists and AIDS patients" -- fighting for marijuana to go mainstream and the changing role weed has played in our culture over time. While we might still be years away from following in the footsteps of our neighbors to the north and introducing legislation that would make weed legal throughout the entire country, as this feature reminds us -- we've come a long way, baby.

Mary Frey on the cover of our March 1993 "Pot Is Hot" issue, shot by Haim Ariav

Hemp, cannabis hemp, muggles, pot, marijuana, Mary Jane, reefer, grass, ganja, bhang, blunt, cheeba, "the kind," dagga, herb, weed, smoke. There are many words to describe a plant we have come to know as a basically harmless recreational drug of the '60s. As hard drug casualties mounted and 12-step programs prospered in the '80s, attitudes changed and pot got a bad name. The War on Drugs raged on, and many pot smokers retreated to the closet for fear of being stigmatized in an era of urine testes and corporate orthodoxy.

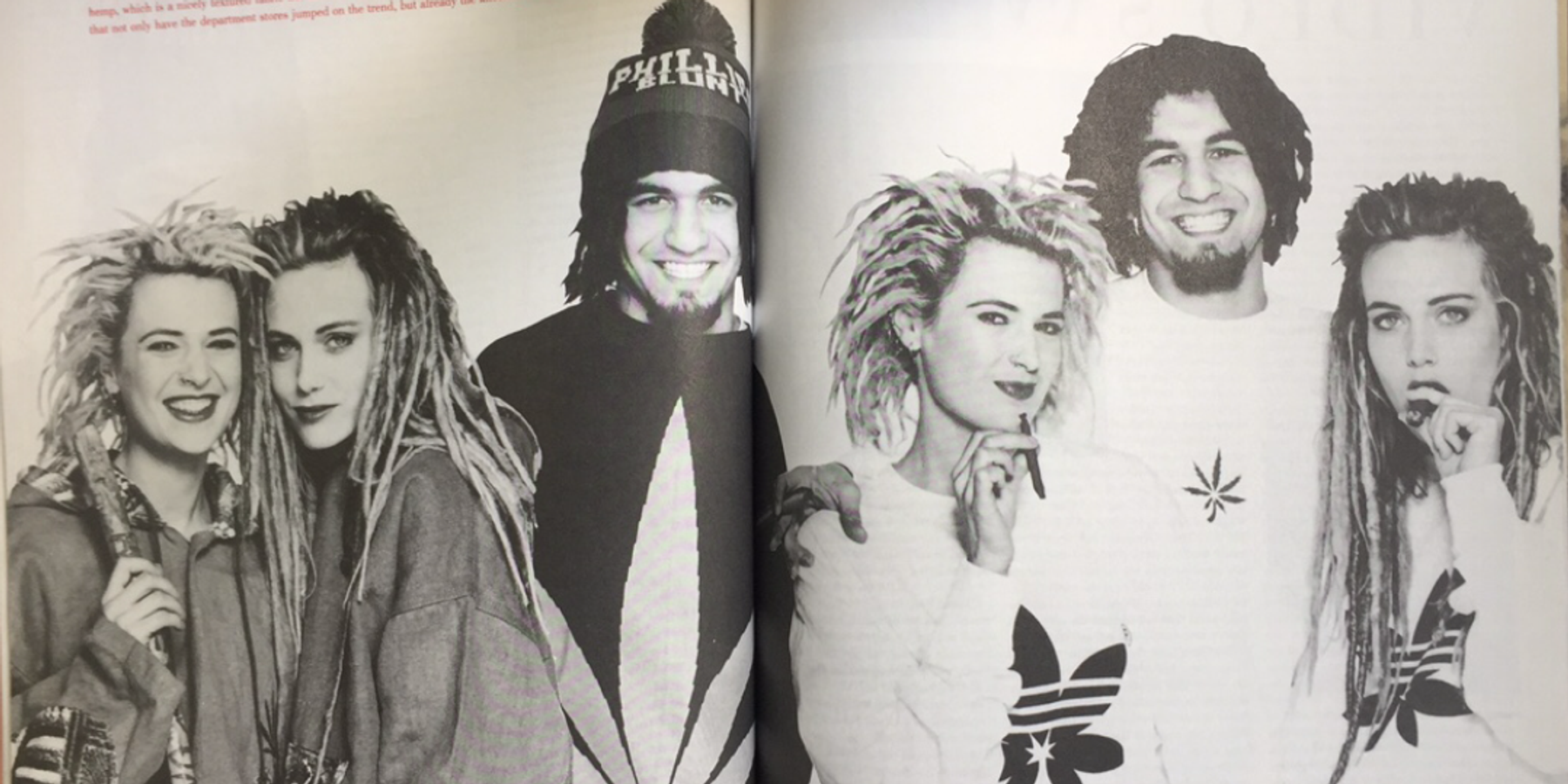

And then it happened. Little more than a year ago, T-shirts bearing the logo of the Phillies Blunt, a cheap cigar of the inner cities, started popping up with uncommon regularity. Those in the know smiled when they saw the ovoid Phillies Blunt logo because they understood the coded message: a blunt is a joint made of marijuana rolled up in the inner leaf of a Phillies. Soon Beastie Boy Adam Horowitz wore the T-shirt on MTV and B. Real of Cypress Hill -- whose hit album is littered with references to marijuana -- sported one in a video.

No longer a retro-issue, pot smoking is now cool with a new generation, looking at it through a different set of binoculars. And they are not alone. Over the past 10 years, another branch of the family tree has been rethinking its views on marijuana and coming up with some startling, revolutionary ideas. Out in San Fernando Valley, California, Jack Herer and Capt. Ed had founded an organization called HEMP (Help End Marijuana Prohibition), focusing on educating the public on the wonders of the plant -- and its medicinal, agricultural, economic and environmental potential. More importantly, he published The Emperor Wears No Clothes: The Authoritative Historical Record of the Cannabis Plant, Marijuana Prohibition & How Hemp Can Still Save the World, a book that has become an underground classic, photocopied and passed along head-to-head. With The Emperor as its rallying point, the dormant movement was revived and suddenly politically correct again. Pro-pot people were now hemp activists out to change the world.

And why not? We'd seen it happen once before when a coalition of leftists, pot heads and common citizens marched to stop the Vietnam War. In its day, that seemed as unlikely a possibility as the legalization of hemp must appear today. But dig it. We used to be afraid of the Communists. And whatever happened to the Berlin Wall?

The AIDS epidemic has also added pressure on the government to approve marijuana for medical use. Smoking marijuana can stimulate the appetites of AIDS patients. It is known to relieve the symptoms of cancer treatments like chemotherapy as well as multiple sclerosis and glaucoma.

To find out how rockers, rappers, Dead Heads, environmentalists and AIDS patients are coming together to save the world, we went to High Times magazine and met with Editor in Chief Steve Hager. Like the culture it covered, HT was mired in the past, but with the arrival of Hager in 1987, its fortunes changed as it began to focus on the budding hemp movement. "I think the big turnaround came when we got hold of Jack Herer's book. It blew my mind," says Hager. "After our issue came out with Jerry Garcia on the cover and an excerpt of the book inside, that was it. The Dead Head underground spread the story everywhere. And it totally changed a lot of people's perspective on the plant."

What they found when they read The Emperor was a wealth of information about hemp that had been buried by history and by powerful corporate interests. Their reaction was similar to Herer's when he made his powerful discovery. "When I joined the movement, the prime reason was I smoked pot and I wanted it legal. Then I met some kids -- this was back in 1973 -- who told me that hemp used to be paper, fiber, used to sew rugs... Along about 1974 my partner Capt. Ed and I had a vision -- we were stoned at the time -- and we said, you know it really grows better than any other plant. It grows the biggest and the best with the least amount of chemicals. And it's the only plant on earth that leaves the ground healthier for having grown there. I just had to say that to myself 700 or 800 times. And once we had come up with that conclusion, we came up with others."

The Emperor is an eye-opener, possibly even one of those rare works -- like Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, Rachel Carson's Silent Spring, The Pentagon Papers -- that will change the way people and the government think and act. Recently, Herer's found a new audience for his views in Hollywood. "There are three or four screenplays being written on hemp right now. I've been spending more time at Beverly Hills and Bel-Air parties explaining this to people in the last three months than I did in the last 17 years."

He's telling them how hemp was widely available until 50 years ago when it was outlawed, how it was used medicinally in many parts of the world until the turn of this century and how young entrepreneurs are now buying up as much hemp as they can get their hands on. He'd tell of DuPont's interest in outlawing hemp in favor of cotton so they could sell pesticides that protected the plant and ruined the environment; and of the Jim Crow origins of the anti-marijuana laws.

But no amount of cajoling, arguing, convincing or rationalizing could have brought people around if it wasn't for the War on Drugs. Larry Sloman, editor of High Times from 1979-84, and author of the seminal book Reefer Madness, saw it coming. "In the '60s pot was tied into a social movement that was about expanding one's mind, being anti-establishment and anti-war. By the time I left no one wanted to know anymore. They were just using pot to get blotto."

What woke these people up was the War on Drugs. Penalties for dealing became harsher, driving prices up and many low-level dealers out of the business. It got to the point where it was easier to buy crack on the corner than pot. Over at HT they were feeling the effects of the war as well and steering their readers toward new ways of attaining the weed. "We said stop buying drugs from criminals. Let's just grow it ourselves," says Hager.

High Times' growing constituency now includes not only rockers like the Black Crowes, but rappers B. Real of Cypress Hill and Redman -- who appeared on the magazine's cover extolling the virtues of hemp and showing off their blunt-rolling abilities. To many in the inner cities, blunts have become a natural-high drug-of-choice, replacing harder options whose devastation can be clearly tracked throughout the neighborhood. As clearly as rap is anti-hard drugs, it is pro-pot. For every anti-drug anthem by KRS-1 or Public Enemy, there's also songs like Redman's "How to Roll a Blunt," Cypress Hill's "Stoned is the Way of the Walk," Tone Loc's "Mean Green" and Goldmoney's "W-E-E-D."

Over at NORML, the oldest advocacy group for the legalization of marijuana, they are feeling the vibrations. Long dormant -- and considered by Herer and others to have been a hindrance to the hemp movement -- it's waking up, says Coordinator of Special Events Dan Wooten from his Washington, D.C. office. "This year it's medical marijuana we are focusing on. We should start research immediately on this medicine and its uses. It's the humane, compassionate thing to do. We have the largest closet army of any issue. Once we get it going, the politicians are either going to have to do it -- or get out of the way."

The recent national "grass" roots marijuana movement has only just begun. Still in its formative stages, and just now coalescing, observers agree that we are seeing only the germ of a social, political and cultural movement whose full impact and size we may not know for years to come. What we have now is only an inkling of just how broad a base of support there is already for some form of legal and social acceptance of marijuana: from far-right Conservatives like William F. Buckley to the ACLU to Clinton's nominee for surgeon general Dr. Jocelyn Elders; from fashion to rap to rock 'n' roll, there's a vast structural framework already in place capable of mobilizing a massive voice for change.

PAPER columnist Steven Blush, publisher of Seconds magazine and writer for HT, was among the early few to spot the scope of such an alliance between rock, rap, youth culture and pot. "I began to notice that musicians across-the-board were talking about smoking, about the ecological and health benefits. Pot appealed to everyone for different reasons, including leftist alternative rockers like Nirvana, who are attracted to the p.c. hemp politics, rock bands that just like to get stoned and rappers like Cypress Hill who bring in an Afro-Earth sensibility." A major event in this burgeoning movement was a panel Blush organized and moderated at the New Music Seminar last summer, "Pot in Pop: Let's Be Blunt," which included Cypress Hill's B. Real, Dave Windorf of Monster Magnet, Rude Boy from Urban Dance Squad, Rum-DMC/De La Soul manager Mike Scott, Sub Pop's reluctant champion of Seattle grunge rock Bruce Pavitt and representatives from HT and NORML. "Everyone came to laugh at a bunch of stoners," explains Blush. "We were all stoned, but it turned out everyone had plenty to say and did so in a relatively intelligent fashion." These talented and successful figures know how to express themselves, and they're the ones people actually listen to.

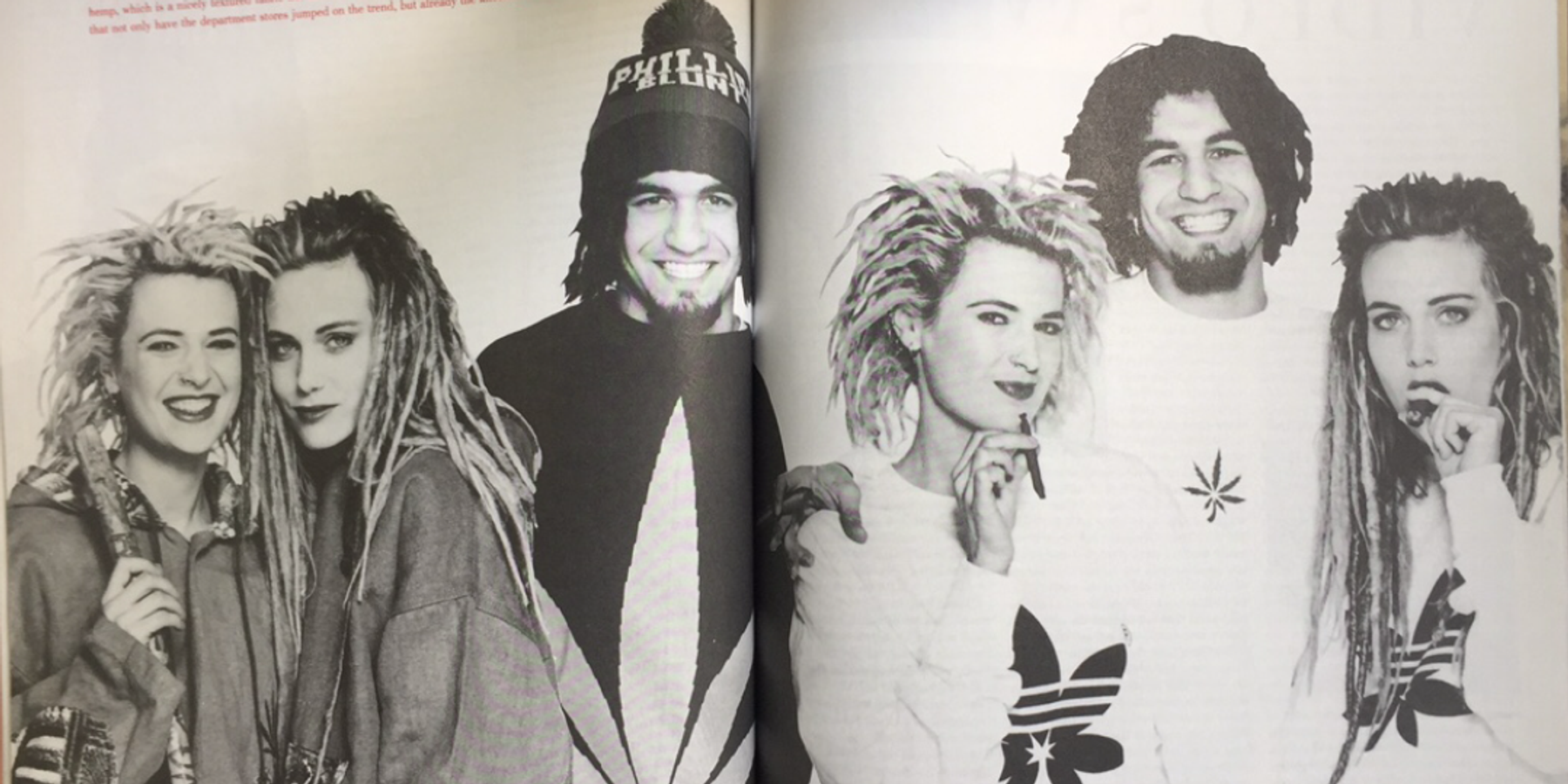

For all the appeal of pot culture's current array of spokesmen, a great deal of their success in reaching an audience has to be attributed to the fact that the audience was already there. Jack Herer, who opened the eyes of so many to the promise of pot and the ongoing conspiracy against it; Willie Nelson, the first real megastar to publicly endorse marijuana and come out of the proverbial closet as a user (even admitting to having smoked it at the White House while a guest of President Carter); Cypress Hill, The Beastie Boys, Gangstarr, De La Soul, Tone Loc, Sinead O'Connor, Black Crowes, Nirvana, Jane's Addiction, Slayer, Tad, Primus and the Butthole Surfers; clothing designers like GAT, GFS, Weedwear, 555 Soul, who's helped to make pot fashionable -- all have helped promote a pro-pot message to their respective audiences.

GFS (an acronym for its three creative founders Gerb, Futura and Stash) formed their street-hip fashion/design company, Not From Concentrate, in late '91 and produced one of their first T-shirts, Phillies Blunt, in January 1992. GFS started out by just giving the shirts to their friends in the know, including Beastie Boy Ad Rock and B. Real of Cypress Hill. Soon these bands started wearing their shirts onstage, in magazine fashion shoots and on TV, where they not only talked about their music and their careers but about pot itself. Next thing you know Phillies Blunt was everywhere -- on the media and on the streets. "It totally changed our lives," Futura admits, pleased but a bit overwhelmed by all the attention. "We were sitting around in the summer of '91 listening to the Cypress Hill record and it was like, 'Yeah, we support that shit.' They really kicked the doors open."

How big has this national cheeba fever gotten? That so many, including our current President and Vice President, have at one time smoked dope is ammunition on some level for pot activists and proponents, but it's not really indicative of this magical plant's rising status within the youth culture. The potency of today's marijuana movement is one that could have only come about socially after pot was totally reinvented as a cultural term. Marijuana as a contemporary signifier bears little resemblance to its previous incarnations as a hippie icon. Pot today is no longer an Aquarian Age plant of Flower Power; It is the fin de siecle peace symbol for the '90s appropriated in the subcultural discourse of sharp, smart, chic fashion; a sociopolitical flag around which urban hip-hop society rallies for a more benevolent, positive and peaceful escape; and an end-of-the-millennium organic god-given solution to the ecological horrors now threatening our planet.

One number that does stand out is the "head" count of some 60,000 attending last spring's Third Annual Great Atlanta Pot Festival. What brought the congregation at the Atlanta Festival to such massive proportions? The answer is simple, and right on the money when it comes to understanding the renewed cachet of pot: the headlining band was the platinum-selling Black Crowes.

Paul Cornwell, Railroad Records honcho, longtime NORML executive, organizer of pot rallies and producer of the Atlanta festival, is well-aware of this pot dynamic. "A lot of big music acts have come out of the closet about smoking pot. If more straights, more organizations, more bands, begin to express their belief, and demand their rights as pot smokers, we'll continue to move forward."

For all his enthusiasm, Cornwell remains more cautionary about the rising tide of pot populism. "It was a great party, but it doesn't change the world if the people out there don't act on it, don't writer their Congressmen or jam the switchboards of their local officials with so many phone calls they'll have no choice but to listen." Busy at work lining up this year's slate, Cornwell also expressed his belief that the recent boom in hemp apparel has strong potential for adding to the momentum of the movement. "I've been trying to get the textile industry interested in hemp for years. The more hemp clothing manufactured, the more the quality will go up and the prices will go down. Hemp in everyday living has a more real feel to it. Fashion is important," says Cornwell, quickly adding, "But not if it's all at the expense of a brother or sister doing 10 to 15 years without saying a word. Let's make it fashionable to be legal."