Kelela is running late. When she finally hops on the line, she's talking to me while stepping into a taxi, but we lose connection when the vehicle drives through a tunnel. A few minutes later, she calls me back and we pick up where we left off. This back and forth process is similar to what it's felt like waiting for the arrival of her debut album, Take Me Apart, for the past few years.

In a way, Kelela sort of revolves in a future pop universe that we're incapable of tapping into. Her debut album, which finally dropped this October, orbits between the worlds of pop and R&B. One concept that Kelela really sheds light on within this project is visibility -- the idea of being seen and heard in one's truest form. To be black and a woman in America is to defy the odds that are stacked against you every single day. Instead of treating the experience of black womanhood as a heavy burden, Kelela demands that black women bask in their glow and celebrate the triumphs when they come.

While the 2015 Hallucinogen EP served as a breakup record, (at least it did for me), Take Me Apart is about giving someone permission to have every piece of you that there is to offer, but to also put you back together again. For Kelela, every aspect of the album—from the cover and the font to the tracks themselves—is very deliberate. The journey to reach this point may have taken longer than she initially anticipated, but it was ultimately worth it because she did it her way from start to finish.

I know that it's taken awhile for this album release to come about, but I honestly don't think it could have happened at a better time in terms of everything that has been going on in our country right now. After listening to it over the past few days, it's made me feel very grounded despite the fact that so many things are being turned upside down on a daily basis.

Wow, that's so cool. Thank you.

How have you been feeling lately?

I feel really good. I feel very happy to be at this part of the process. I think I just spent so much time trying to make my best thing and feeling behind and sort of inadequate on some level. It feels really good and healing to be able to reflect on it through these interviews. It's a good, healthy feeling, [I'm] really grateful to be able to do this for a living. It's really special.

It is true that in the past few years the larger context of the world has illuminated [inequality and racism] for everybody. It's shocking to see black people being killed on camera, but it is not surprising, if that makes sense. I've always felt like that is what I'm up against -- or I'm always facing a context that is that hostile, but I could never show that before and I think that's the thing that's different. White people know about it now, or white people believe us.

Being a black woman in any field has its challenges, but I feel like to be black and a woman in a creative field comes with a whole other set of obstacles that the majority people are unaware of. How do you personally go about maintaining power in this industry?

The music industry is organized in a more blatantly racist way than one might think from the outside, that's the first part. When you think about the music industry, you think about the artists. And for the most part, people of color are thinking about the output and measuring our success as people of color, as black people, in that way rather than in a, "Who's the CEO? Who's in a position of power? Who's calling the shots?" type of way.

On top of that, just learning about the actual business and trying to understand what the fuck is going on, and needing to consult white people in order to "make the best decisions." I will say white women are definitely [credited] for their craftiness and the deliberate nature with which they approach their art. They get more credit for that type of thing.

It's damn near impossible for people to acknowledge in practice and in real, everyday interactions that you have an idea of what you're doing, that you are deliberate, are putting things together in a particular type of way. Anytime that it comes to that stuff the assumption is that, "You don't know what you're doing so I have to tell you what's best for you." That is the space that I'm entering in the music industry to varying degrees, but it's a trope. Even outside the music industry, for my black women peers who are visual artists, it's the same thing. When they do their work for the first time, or become visible, there's a need to tell them what they're referencing and what they're doing.

Historically, the way that people in this country see black women's contributions—specifically with music—is that it's just pouring out of us. That we just naturally vomit up talent and cuteness, and then some guy is sitting there and making it crafty, refining it, and making it be the thing that it is. It's difficult in a few different ways—it's difficult in a really practical, just trying to make my vision a reality type of way. Like, "Stop telling me what I'm doing and stop telling me what you think is the best thing." And then there's the other part: I'm trying to do business here and my only option is to deal with white guys.

Even in the realm of music, in an urban department at a major label, it's very likely that the head of the department may not be black, which is weird. From the outside, you think that that would never be the case. You have 40 million artists that are black and the sound of everybody's music is really evoking a lot of blackness, and so that there wouldn't be a lot of black people at the table is something you don't expect.

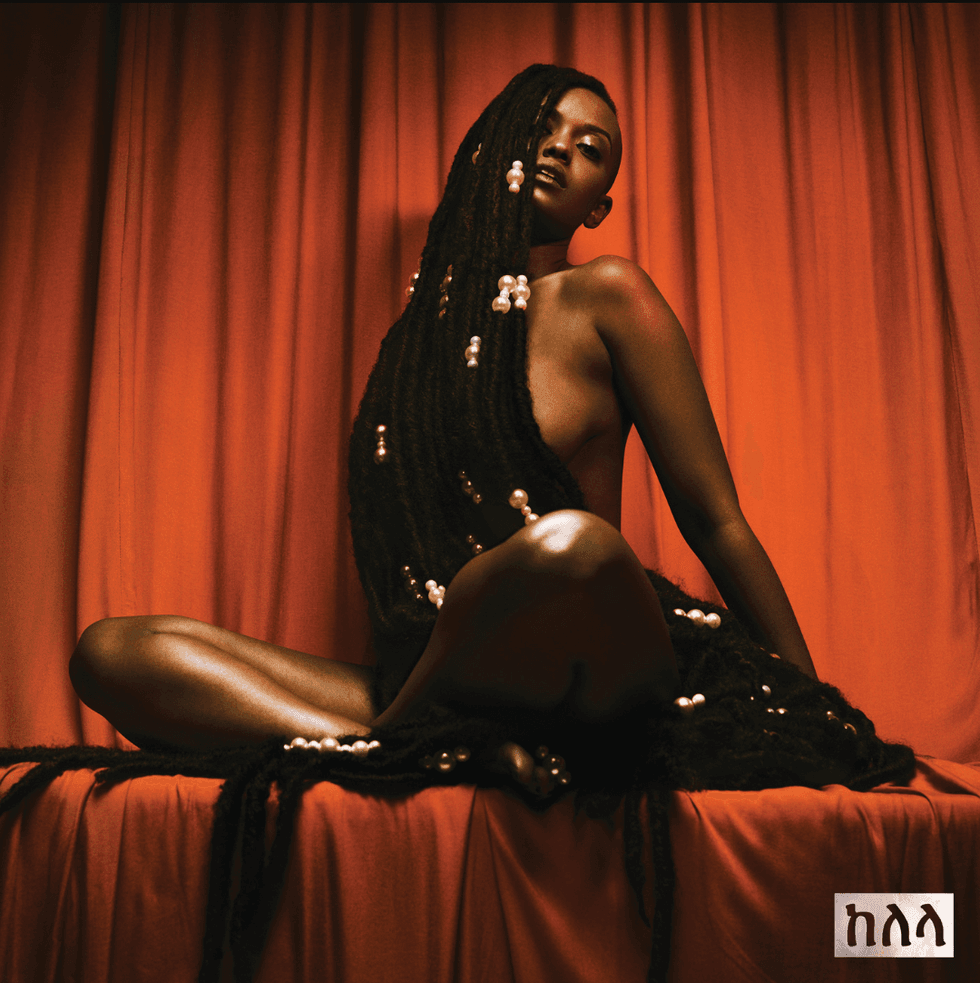

I love the cover for Take Me Apart. What made you decide on this image? Could you also explain your vision for the other photos that are included in this spread?

Thank you so much. For the cover, initially I was looking at styling options, and the problem is that the album feels cohesive, but it doesn't feel like a singular sort of approach. There are variations in the album that I couldn't quite fit into one style of clothing. Physical clothing seemed very oppressive so I kind of knew in the moment that it had to be a vulnerable image. At the top of my head, it was clear, "Well, that means I'm probably going to have to be naked," and then wanting to say something very extra and black. The intersection of that and something regal and really important-looking is the thing that I really wanted to evoke through the album cover.

The title has so many meanings. On the emotional level, there's a courage that one needs to have in order to invite someone to take them apart. It's not intuitive; nobody would willingly ask somebody to break them down, but I wanted to also say that's the type of courage that someone needs to be comfortable with that. It's being comfortably uncomfortable, and for me, that's kind of where I come from, so I wanted the image to do the same. The type of vulnerability that I'm talking about on the phone, I wanted that to translate with the imagery, so that's definitely why I went nude on the cover. The pearls take it outside of what we know.

On a general level as an artist, I don't feel adherence to any one aesthetic so it's really important to me that you see that cover and then the next thing you see is me in a blonde wig. They're all [images] that dismantle the conclusions that people draw based on my appearance. Specifically, there are so many things about black women that is code for so much. So much information is communicated through our hair. That was why I really wanted the cover and the album artwork to sit alongside a video like "LMK," because it dismantles some notions about what I am and what I'm not. The goal for me is to be everything and nothing at all. That's where it came from.

The Amharic logo in the corner is such a nice touch as well.

Thank you. I'm very wary about evoking my Ethiopianness—wary not in an, "I'm not proud" type of way, but in a way because there's so many connotations and so much information that's also communicated through what it means to be Ethiopian. When people hear the word Ethiopian, there's a lot of stuff that comes up. I wanted to really be responsible and that logo was encouraged by my friend and collaborator Mischa Notcutt. She's my right hand on the visual stuff. She was like, "I feel like you can do it." That's my name in Amharic, and it's part of me so I put it on the cover.

I didn't really know anything about Ethiopian culture until I went to college in D.C. in 2011.

Did you go to Howard?!

No, I went to American University.

I went to American University!

I know, that's something I've been wanting to chat with you about! Some of the issues that you brought up in your interview with The New York Times Magazine are still so relevant today, specifically with the black community at AU feeling alienated. It's so wild.

It's wild. It's wild for a school to be in D.C. and for black people at any university to be feeling alienated. I remember when I got there, I looked through the yearbooks from the '70s and '80s and there were so many more black students. I did this project one time for my white privilege and social justice class where I did a study on all of the brochures and propaganda that is dispensed in the school with photographs in it. I counted the number of people in photographs and then I counted the percentage of people of color depicted in those photographs and compared those numbers that are dispensed to us when we think about coming to the school.

That ratio was something like 75% of the people in those photographs are people of color. What that does is, all of us in the classroom are like, "We got duped because we thought there was going to be way more black people here!" That was what I was interested in finding out about. I found that there was a period in the '70s and the '80s when affirmative actions programs kicked in and there was a program at American University that allowed D.C. residents to get in-state tuition -- but then they got rid of it during the Reagan era. So you can see the stark difference before and after, and what that must have done to an entire generation of our parents that were able to go to school. I definitely had a big issue with that…

When I was going to school there, white liberalism hadn't been overturned in the way it is right now. In that period, I was really frustrated with the School of International Service, specifically. I took one sociology class for SIS, and essentially what I was finding problematic was there was less of a culture of implicating oneself through problems that we see in the world. Sociology and anthropology, you're kind of not allowed to be like, "That problem over there exists because people over there are like this and they're over there doing this." You're not allowed to say stuff like that, people can call you out.

But in the School of International Service, it was kind of normalized and justified by the teachers in this way. The culture was not like, "What are we doing to contribute to these issues?" It doesn't start with yourself and that's the issue I find most prevalent in that culture—diplomacy, international studies, international politics, economics—there's just less of that culture. People feel really international all of a sudden, even though their skull is still so small. That is one of the things I really wanted to eliminate, but I sort of quit before I could really do it.

Every time I go back to D.C., it feels more different to me. It's almost like a stranger in some ways because it's always changing. What was it like for you growing up in the DMV and how did living in this area shape the person you've become?

I grew up in a layered reality of being black, of being a woman, of being Ethiopian, of being so many things. The connections to jazz and my experience with innovative and experimental R&B -- before people were even saying the words "R and B," I had a relationship with that type of music through the scene that exists in D.C. It's also a very academic town, so the culture of analysis and thinking about your reality is something that I don't think is particular to D.C., but there is a culture of that there.

There's so many things, it's hard to pin down, but I would say that there's an intersectional reality that I live in and one that is pretty common in D.C. I guess [one] is second-generation Ethiopian women who feel connected to their blackness in a particular way. I can't really speak to it because I've always felt kind of alone and moving through scenes rather than being integral or really centrally part of any one.

Vulnerability is a big theme that comes across on Take Me Apart. I don't know about you, but I've always been a very sensitive person and it took me a long time to even learn how to validate my feelings and be comfortable with vulnerability. Anytime I see those "fragile handle with care" stickers on a package I feel so understood! [Laughs] When I listen to the album, it reminds of one of Jenny Holzer's Truisim pieces that reads "It is in your self-interest to find a way to be very tender."

Yes, girl. That's what I wanted to illuminate. I've always wanted to say that that's the coolest thing. It's weird because it's not the coolest thing to people. It's always been baffling to me.

It's interesting because we're still having to deal with the perception of being a "strong black woman," but with that it's viewed as weak to express emotions. I personally think that if you can allow yourself to feel, that's real strength.

There is a lot of power in that. There's so much power in that act and I think black women—especially singers—have helped so many people in the world get in touch with that vulnerability. Black people in general have, but I think that tenderness and approach that is soft and strong—strong because it's soft, and particularly strong because we're being soft and tender in a world that fucking hates us and doesn't want us to thrive. In the face of so much passive attack and trying to operate in a world that's built for white men—and now more and more built for black men—it is one of the most difficult things to be vulnerable when you are coming from that place.

It's crucial that that be part of the message. It's not just tenderness, it's tenderness coming from a black womanhood experience. When people want to feel soft and cozy and make out, a lot of times they're putting on something that is made by black people—specifically black women—so that is something I've always been interested in.

I've always appreciated the presence of intimacy in your music. What relationships have been the most impactful in your life in terms of setting a good example of what real love is?

My romantic relationships I would say have done that, and then my parents. My parents have shown me what love looks like in quite a few ways, through the love that they have for each other despite their differences. The way that they've wanted to work together to help me be my best self in the world is such a display of love and care. I think about why I would be feeling equipped and strong enough to be this vulnerable in the world. I think that is something that my parents made me feel—they made me feel comfortable so that I would be willing to throw myself out there right now.

What I write about is essentially how I do that in my romantic relationships. Through each of them, I've definitely been able to grow as a human being, and finding self-love is probably the biggest one that has come up. It's the one that I think you find out through several experiences, you require that first and then you can really properly give it to somebody else. All three of my long-term partners have really shown me that, and even people that I've had more casual interactions with have as well.

I'm looking for love I guess is the bottom line—I'm looking for it, I'm trying to find it and eventually I'll extract that shit. I will find it! [Laughs] Even in the most unloving situation, I'm going to turn it around and that's kind of what I do in the record. Trying not to fall into victimhood, so all of the lyrics are really centered around finding a way to talk about what's happening with me when I feel hurt.