So much of being queer — besides taking crouching selfies in one of Yayoi Kusama's infinity mirrors — is being in a constant state of questioning. We obsess over the things we've learned (either consciously or adopted through social cues), our wants and desires, and how we move through the world at large. It's both an embrace and rejection of stereotypes — an overlap that's perfect for writer Jen Winston to examine the many facets of her own identity, specifically her bisexuality.

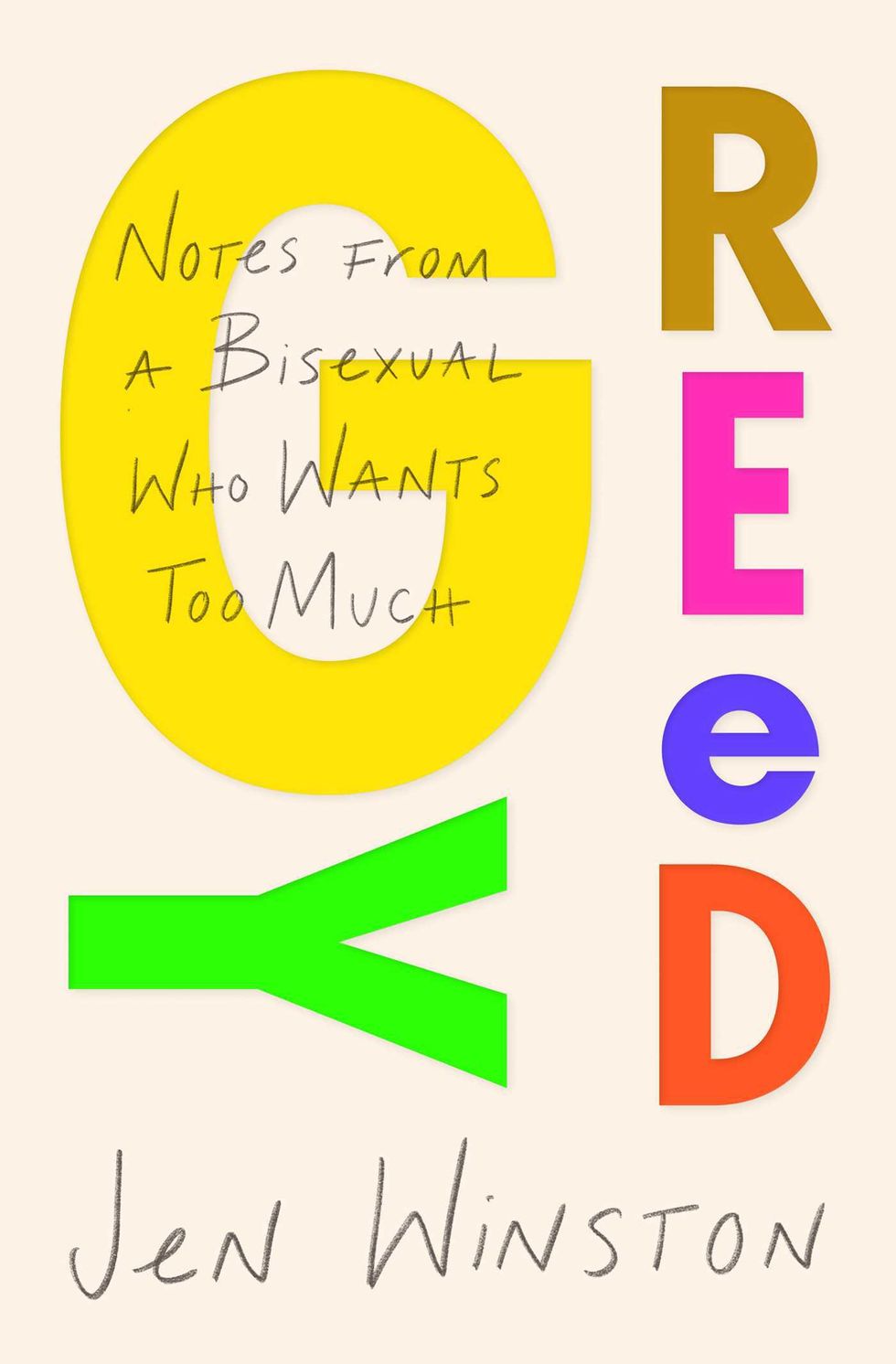

In Greedy: Notes From a Bisexual Who Wants Too Much, out now, Winston interrogates her upbringing — both inside and outside the household — and how both have shaped her process of self-discovery. Cognizant of her bisexuality from an early age, Winston has struggled to find a way to define it — and herself — on her own terms. Her debut combines memoir and queer theory, resulting in an essay collection that's at once relatable, laugh-out-loud funny and refreshingly illuminating.

Winston challenges us to think beyond the binary systems we've adopted as a result of colonial expansion into the West and other Indigenous territories around the world —yes, we go there, literally. Above all else, Greedy is unafraid of mess, vulnerability, and outgrowing the things we previously considered as absolute.

PAPER caught up with the debut author in the midst of the rapturous reception of her book to talk more about her contention with bi stereotypes, reveling in the mess that is identity and a lot more, below. Greedy: Notes from a Bisexual Who Wants Too Much is available for purchase here.

From one debut author to another, CONGRATULATIONS! Notice how I'm not ending this question with an actual question, because I know from experience the wide array of emotions you're probably cycling through. Why don't you just tell me what you want pertaining to the release of your first book?

As a bisexual Libra with ADHD, "What do you want?" is a tough question! But I'll do my best.

My main goal for this book was to make the bi label more accessible and to prove that bi people are actually allowed to be proud of it. I grew up thinking of bisexuality as a behavior (see: drunken make-outs, occasional threesomes) rather than an identity I could claim or get behind. I thought everyone was bi and in turn thought being bi wasn't "special." In a bold original take, I blame this on the media: onscreen characters rarely describe themselves as bi, but they frequently "behave" bisexuality by hooking up with multiple genders (usually wrecking a home or two along the way). "Show don't tell" is cute as a storytelling approach, but it means hardly anyone actually says "bisexual" out loud.

That's why I insisted on explicitly using the label in this book — I wanted it to feel almost too on the nose. I wrote Greedy for my younger self and that's what teen Jen needed to hear.

Your book is both a complete joy and vital not just to the conversation surrounding bisexuality, but the conversation-at-large about identity and the perpetually transitional state it's in. Did you start writing your book with these ideas in mind from the get-go, or were they fruits (sorry) you picked along the way?

No need to apologize! Bad puns are bi culture, so this actually makes me feel safe.

I came up with the title before I wrote a page. I knew I wanted to reclaim bi stereotypes because poking at them would allow me to poke at other concepts (mainly gender, but also monogamy, ableism and white supremacy). But the book's themes really crystallized for me when I encountered the work of bi theorist Shiri Eisner. Eisner wrote Bi: Notes for a Bisexual Revolution, which helped me realize that bisexuality doesn't reinforce binaries — it actually does the opposite, pushing us to find stability beyond predefined boxes and existing social norms.

Also: Eisner describes bisexual confusion as "a destabilizing agent of social change." I mean, holy shit, right? The first time I read that, I got full-body chills. Suddenly my confusion — the thing I'd always seen as my detriment — had become my superpower.

I love that you title first. I too often title first and I know from talking to other writers that we are the minority here. You tell the reader where the word "greedy" comes from in this particular context, but why did you choose it as the title from the onset?

Cheers to titling first! Maybe it's because I once wrote clickbait for a living, but I feel like titling is especially critical in the so-called "attention economy" — it tells people what to expect and why to listen. I wanted to communicate that my book was about being a horny bisexual stereotype and Greedy nailed that. The only alt I liked even half as much was, Maybe Dick. (Melville, eat your heart out.)

Greedy also worked because so much of my shame around being bisexual stemmed from the "-sexual." That's why I didn't want to come out to my parents or coworkers — I didn't want them to think of me as a slut (especially because I was one!). But now sex positivity is a huge part of my politics, so going all-in on the "greedy bisexual" trope helped me address both stigmas at the same time.

"Bisexuality doesn't reinforce binaries — it actually does the opposite, pushing us to find stability beyond predefined boxes and existing social norms."

It's evident that a lot of care and attention went into the research you've incorporated into this book. What was it like preparing and organizing all of these sources? (Subtext: please share how to be smart with me.)

My god, I wish I knew. I was not ready for the amount of research this book required and not just for the queer theory parts either. When writing, say, a personal essay set in the late '90s and wanting to make a joke about being scared, I wound up googling every horror movie from that era, then going down a rabbit hole trying to see if Bride of Chucky aged well (it didn't).

My process was a mess, so I have zero wisdom to impart. All I know is that if I ever have that many tabs open again, get me some fresh air ASAP.

There's a lot of vulnerability in these pages. How did you take care of yourself emotionally when writing them?

I thought I'd be totally fine dredging up my past sexual assaults. I figured I'd finished dealing with that trauma, but as I started writing I realized that what I'd actually done was avoid it — pushing the pain aside, so I could get back to my busy, capitalist life.

But writing slowed me down and that made everything bubble up. I had to reconcile that these experiences weren't my own fault and that was way harder than it sounds. Though the process was intense, it was also cathartic and necessary, like pulling a bullet out of a wound.

Writing about trauma is hard. For me, it's like, "Am I ready to write about this?" And then that turns into, "Will I ever be ready to write about this?" Have you experienced this? If so, what is your advice for other writers who may be asking themselves the same questions?

Absolutely have experienced this. I guess my biggest piece of advice, especially for memoirists (or anyone who creates art that reflects their own lives), is that you don't have to write about everything. You can process pain off the page and it doesn't make that hurt any less "real."

In my earlier writing, I talked about trauma with so much less complexity. I know some people will eye-roll at my use of content warnings throughout this book, but those warnings actually forced me to show up with more nuance. They took away the element of surprise, which meant I couldn't rely on a traumatic event as a plot device. I think that made the act of writing more healing because it forced me to focus on my emotions and responses more than the events themselves. But work isn't always therapeutic, don't force it.

Identity is often bookended with the word "enough," followed by a question mark. You write, "Am I queer enough?" So much of what we go through as queer people is wondering if we're enough within the identity markers we wish to adopt. How can we move from this mindset?

There's this notion in the queer community that bi people should have "proof" of our queerness — an itemized list of everyone we've ever fucked. I compare it to aspiring waitstaff in NYC who get asked for "New York restaurant experience." How do you get that without that? How do you get queer experience if you need queer experience to be let in?

Bi people — and all queer people — carry so many paradoxical expectations in our heads. The only thing that's helped me has been shifting away from queerness as an individual condition that anyone needs to "qualify for," and moving toward José Esteban Muñoz's idea of queerness as collective utopia — a vision for total liberation. That's my POV these days, and as a result, I've never felt gayer — funny how things work out.

Also, writing about sex in and of itself is An Experience: when you're writing it, you're writing as if no one is going to read it, and then you're like, "Oh, shit, wait, people are going to read this." How have you contended with these oscillating, oftentimes overwhelming, emotions?

There's a reason my book is dedicated, "To my parents, who promised they wouldn't read this." I needed to get that agreement in print before I could relax.

I actually love writing about sex — maybe too much? (A friend recently joked that they'd title their Goodreads review of my book, "We Get It, Jen — You Fuck.") It's definitely strange that people I've never met will now know how I masturbate, that I'm into Shibari and that I've been fingered with a tampon in. But in a way it's comforting? Like we've already gotten that part of the small talk out of the way.

You and I both have a history with nightlife, which was also formative for me as a queer person.

I noticed this while reading your book, too! Maybe we crossed paths in a porn-wallpapered room at a Ladyfag party long ago.

Even though we're far from the first queer people to write about nightlife, I still feel like it's not written about enough. Seedy darkrooms and gritty raves are where so much of queer culture comes alive, yet so many books seem to gloss over those experiences, or at least water them down. I always assumed that's because the public prefers their gays de-sexed and during daytime (another reason I wanted Greedy to be NSFW).

In any case, nightlife has been so pivotal for me — truly like my third parent. I wanted to create a time capsule for some of those nights because it felt like they might fade out of history otherwise; I worried that no one else would tell their stories. That said, it's hilarious that I waxed poetic about the uniqueness of 2013 Rhonda in LA because I went there a month ago and it was a full-on circuit party. You blink and things change.

In some ways, your book reminds me of Heaven by Emerson Whitney. In it they write, "Really, I can't explain myself without making a mess." And it's within this mess they operate and write. The book is about finding comfort in questions that don't necessarily have one — or any — answer(s). I feel like your book is in conversation with this one and many others at that.

When I think about the future of literature, it's folks like you and Whitney, and the many other both emerging and established writers that make me feel like the future (of books at least) is in safe hands. It's like how the kids have Lil Nas X these days.

I'm honored to be in such great queer company! I haven't read Whitney, but damn, do I love mess. [Insert Marie Kondo meme here.]

I love the mess that is bisexual confusion and also love seeing what the act of getting messy can do to art. It's not lost on me that I set out to write a book heavily grounded in language, and the process of writing said book took me into something far more nebulous, deep into the understanding that everything is unanswerable and unknowable — and therein lies the beauty. I love contradictions and it's no coincidence that queer stories are often the ones that help us sit with them — queer people tend to effortlessly hold multiple truths at once.

"Seedy darkrooms and gritty raves are where so much of queer culture comes alive, yet so many books seem to gloss over those experiences, or at least water them down."

Whitey also writes, "The word trans will change in my lifetime, it's inevitable." I'm curious: do you think the malleability of language will ever afford us a time when it will be in equilibrium with how we consider ourselves and our respective identities? Or will we always be straddling lines? I just gave myself a headache!

Honestly, I hope we never reach that equilibrium — I love words and self-expression too much. The danger comes when we see language as rigid and unchanging. Language is our tool — it works for us and not the other way around. Claim your label (if you want!) but don't let it dictate your life. Like my partner always says when I hold the leash: "Walk the dog — don't let the dog walk you."

I love this and I have to agree. I don't think we're supposed to reach that balance because we're always meant to outgrow it and/ or change with it.

Yes, the outgrowing is the best part.

What books were your North Star when writing Greedy?

So many, but when I was lost I often turned to Alexander Chee's How To Write An Autobiographical Novel. I brought that book with me every time I left the house, long after I'd finished it — it became an object for me, a talisman. I also fell in love with its physical form and I swear that for my next book I'll be rolling in style: Deckled edges, French flaps, a colophon — the whole deal.

Any more books from you on the horizon? I'm sure I'm not the only one who is thirsty for more!

This question is also a tough one because I'm still so exhausted (I wrote and published Greedy in less than a year). But much to my body and my partner's chagrin, I'm already thinking about what's next. The first option would be a big departure — it's a novel about a group of queer assassins that explores different ideologies around justice — but part of me worries I'll never finish it and will be doomed to write personal essays forever. If that's the case, my next collection will likely be about adventures in queer parenting. Stay tuned and wish me luck.

Greg Mania is the author of the memoir Born to Be Public.

Photography: Landon Speers

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web