Even cats don't get as many lives as Isaac Mizrahi. There's the fashion prodigy once named the New York Times's "hottest new designer" and featured in the 1995 documentary Unzipped. There's the costume designer who's worked on Broadway and for the Metropolitan Opera. There's the businessman who created ultra-successful lines for QVC and Target ("Some critics warned that designing clothes for Target could tarnish his image, but instead, the deal has boosted Mr. Mizrahi's career," the Wall Street Journal wrote in 2005). There's the talk show host. There's the cabaret performer with sold-out sets at Manhattan's famed Café Carlyle. There's the Project Runway: All Stars judge. The comic book writer. The memoirist.

In all his incarnations, he's been a man of many words, whose tangents aimlessly yet without fail lead back to his original thought. Mizrahi has never been afraid of voicing a strong opinion — even when said opinion isn't the popular one. Such was the case in February when Mizrahi endorsed then-Democratic presidential nominee Mike Bloomberg. The replies were scathing, with many pointing to Bloomberg's record with cutting funding for HIV/AIDS supportive housing contracts as well his stop-and-frisk policy (which he later denounced). "I was very, very surprised that people saw him in a different way, because I don't," says Mizrahi. "I don't see him as this vicious evil oligarch."

Now that Bloomberg is out, Mizrahi has moved on, with his eye still on the goal of ousting the current President. "I mean everybody has to do whatever they can," he says. "Like whoever they're supporting, whatever, but we have to come together and just move this out. We have to move this bad energy out."

Below, in a wide-ranging interview touching on his Jewish roots, a bygone gay New York and the current state of the fashion industry, Mizrahi reflects on over five decades in, out and on the periphery of the fashion industry.

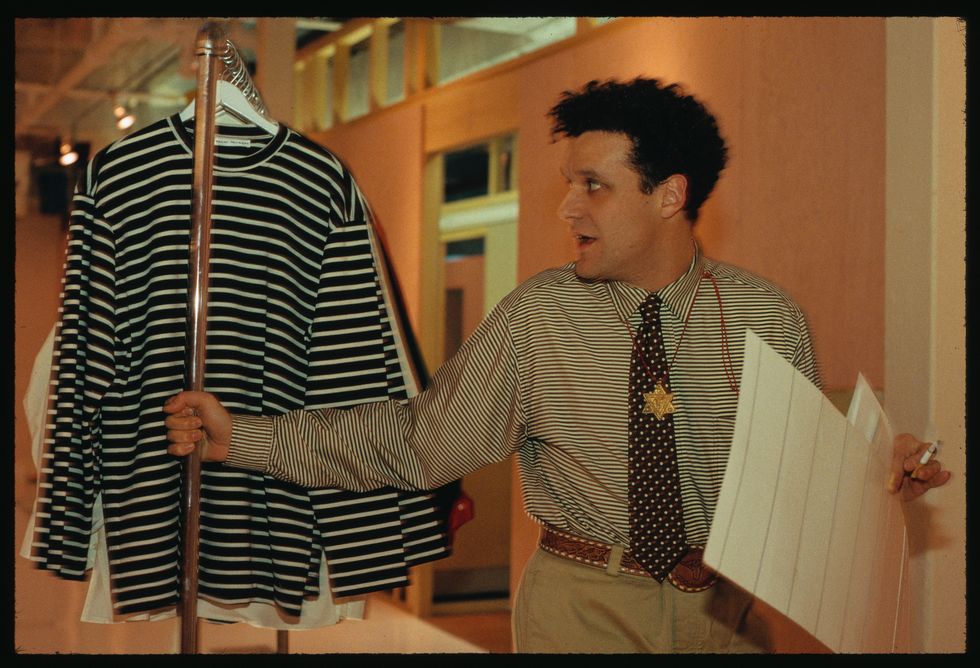

Mizrahi in 1997

I would be remiss to not express gratitude to you for speaking with me today. To say I'm a big fan would be an understatement.

This is amazing to hear. What makes you like me so much? Or rather, what about me makes you so erect at the moment?

I don't think there's any cultural figure that I've connected with more through the years in terms of sensibilities. Your style, obviously. Your Jewish identity. Your flamboyance. Your love for NYC and your pride in that. And the way you look at the world. It's always captured me. So let me start off a little meta. Do you like being interviewed?

I like therapy because you're paying someone to not ask questions and to just listen to you speak, you know? So that's really great. That's like the most fabulous thing in the world. Cause I'm a huge narcissist egomaniac. But I do like being interviewed because I learn from it. And because you know, again, it's about moi. Toujour, darling. Toujour sur moi.

You grew up in an incredibly religious Jewish household in Brooklyn. When did you first become aware of your Judaism?

When I was a kid, we were Jewish. There was no choice in the matter. I was sent to a very Orthodox Yeshiva and the shul I went to was Orthodox, I mean, it was anomalous because it was Sephardic, so low-cut dresses and high heels and big hair. It was this incredible piety, and yet flamboyance. And then in school it was rabbis that looked like rabbis, which to me is more straightforward. If you're going to be a rabbi, you've got to look it, because if you're a rabbi and you smell good and you have a big package, like what kind of bait and switch is that, you know? [Laughs] And their wives wear wigs that make them look purposely worse. I don't understand that. And you're talking to someone who loves a wig. Like, I love the wig, but not for the purpose of making yourself look worse. I used to watch non-Jews on Christmas get presents and we kind of got like shitty presents on Hanukkah. Hanukkah was like, not that glamorous. And there you had Christmas and it was just trees and Santas and Mitzi Gaynor Christmas specials and we had menorahs and the Maccabees. It just didn't feel just, it didn't feel fair. And so I resented it.

As you discuss in your memoir, I.M., growing up there was a conflict between being gay and being Jewish.

When I was a kid, like the idea was so repellent and so gross that even if they called me a fag — which they did 'til I literally puked, every day of my life, that was my fucking nickname. It was building on such a level that you just can't even imagine, but I was resilient. And I don't think that they even understood what it meant. Like I don't even think they understood that men could fuck each other. They didn't even know what they were implying. But somehow I was resilient and I was able to kind of like, default to my feelings, which could not be wrong. And I'm not sure where I got that from. It certainly wasn't from Yeshiva. But I knew that my feelings were not wrong, and that's what guided me.

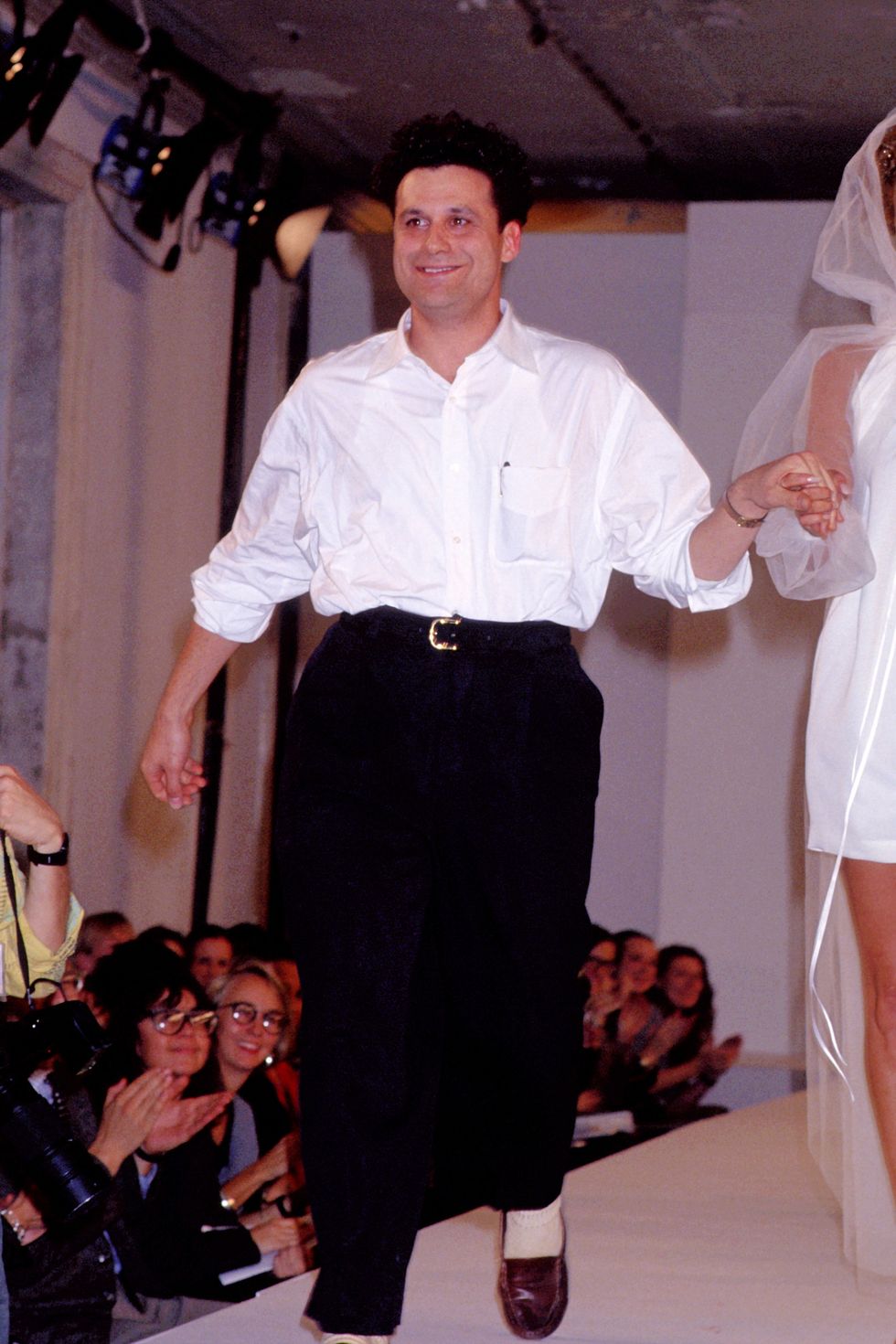

Mizrahi at NYFW circa 1991

So you're 10 years old when your father gives you a sewing machine. And it wasn't the standard gift for a 10-year-old boy at the time. How did you manifest that for yourself?

Well, he didn't give it to me darling. I bought it. I babysat this whole summer and at the end of it I went to the Singer Center when we had this place for the summer in New Jersey on the shore. I wanted my mother to come with me, but instead my father came and he knew everything about sewing machines. He identified a better sewing machine at the Singer Center, an old machine that was so beautiful. And I'm so lucky that he did that and I'm so lucky that he came with me that day. And it was a little more expensive than the machine I had wanted. I actually wanted to buy the kind of modern machine and he kicked in like twenty bucks or something so I could get it. But I bought that machine with my own money. And it wasn't to make clothes. I didn't see clothes as an art form. I saw it more as a kind of like… a daily thing, you know? That's what clothes are about. I mean I love artifice. I love, love it, you know? But I love flesh more. I love bodies more than I love fashion.

What was your relationship like with your father?

I didn't really feel the love from my father. He was a great guy and there were moments obviously, but I felt that he wished I was a different kind of a boy. And so this closeness might've been lost because I think he wanted a different kind of a son that was more interested in fixing things around the house or sports. Even though he wasn't into sports himself. But then eventually he started buying me these attachments for the sewing machine and bringing them for me. And later in my life I sort of realized, or I acknowledged, that that was him kind of like reaching back and sort of showing me some kind of love and care.

So in 1988 you make your runway debut. I spoke to a fashion historian friend ahead of today and he said, "I don't think anyone in my 40 years of fashion burst onto the scene with a first show the way Isaac did." What do you remember from that collection?

I remember that I wasn't present so much in the cultural happening of the show. Like, my head was down for the entire thing. I was looking at bows and shoe ties and the hair and the earrings, if it was set properly. And in those days you booked like twenty girls or seventeen girls and you showed like a lot of clothes and they would change their fucking clothes fast and it was really, really exciting and fun and also hard, you know, it was really hard to get a girl to look like she's been in those clothes when she literally just pulled them on and barely zipped the zipper up and changed her tights and her shoes and her hair. And now this has to be adjusted. And that.

And when I came onto the runway, I saw Veronica Webb, she came off at the end of the show before I made my bow, and she said to me, "you're the king of New York." And I said to her "stop fucking with me." Like I thought that she was being nice because I thought I was about to be destroyed. And I walked onto the runway onto this crazy standing ovation, and not just from my friends, but from everybody… from everybody in that room. But that's where I was during the whole show. I was not present in the glory. I was present in the trenches of it, you know, the scrum. I was in the scrum of it.

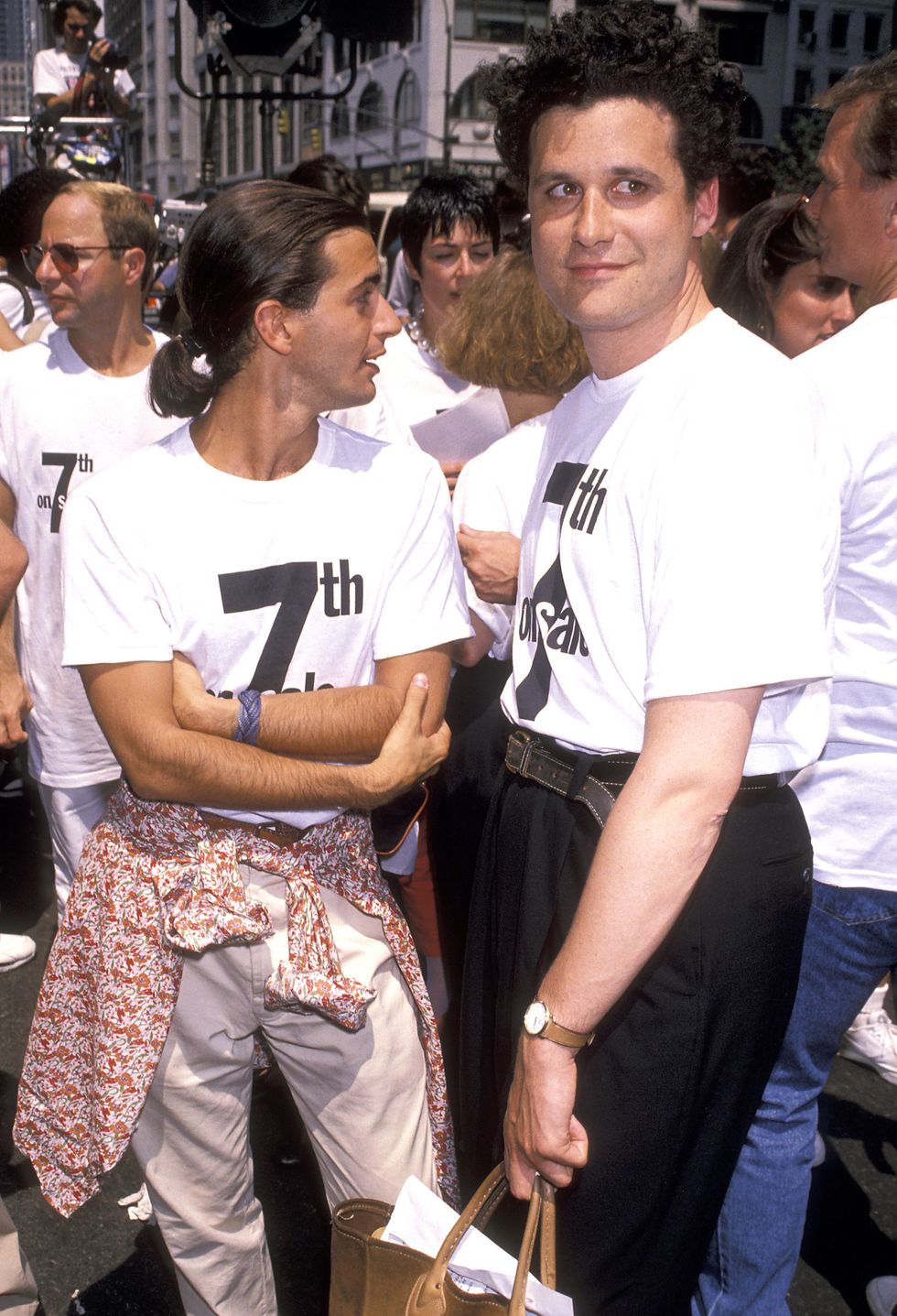

With Marc Jacobs at 7th On Sale 1990

Many credit you with really bringing to prominence the celebrity front row —

Oh really? You might be right, yeah.

Nowadays that's sort of standard fare for the runway, but it wasn't at a time. Where did that impulse first come from to invite celebrities to sit front row to fashion?

Well, you know, a lot of it just happened. And I didn't really try that hard. I've never paid anybody to sit in the front row. I mean that's a whole invention of, I don't know whose, but to me it's sick when you have to pay people to sit in your front row. What the hell? You've got to tell me what that means. Like, what does that mean?

Liza Minnelli happened to be a friend of mine, and she was interested in coming and so she came. Or Sandra [Bernhard], and Sandra brought Roseanne and Madonna would come to the show and Robert De Niro because he liked seeing the models. I mean, he didn't give a shit about my clothes. And Russell Simmons insisted on coming to my shows. And I was happy to have them 'cause it was a glamorous scene, you know? That's what it was. It was just this glamorous actual scene.

Obviously film and art history are great reference points for your work. Where do you tend to seek out inspiration?

You know, so many times I'm walking down the street and I'm like, "Oh my God, what is that?" And I will follow somebody and like obsessively stare at their shoes, which are like a pair of Adidas or something. But there's something that just happened to them, like they stepped in shit or something, and it's really beautiful to me.

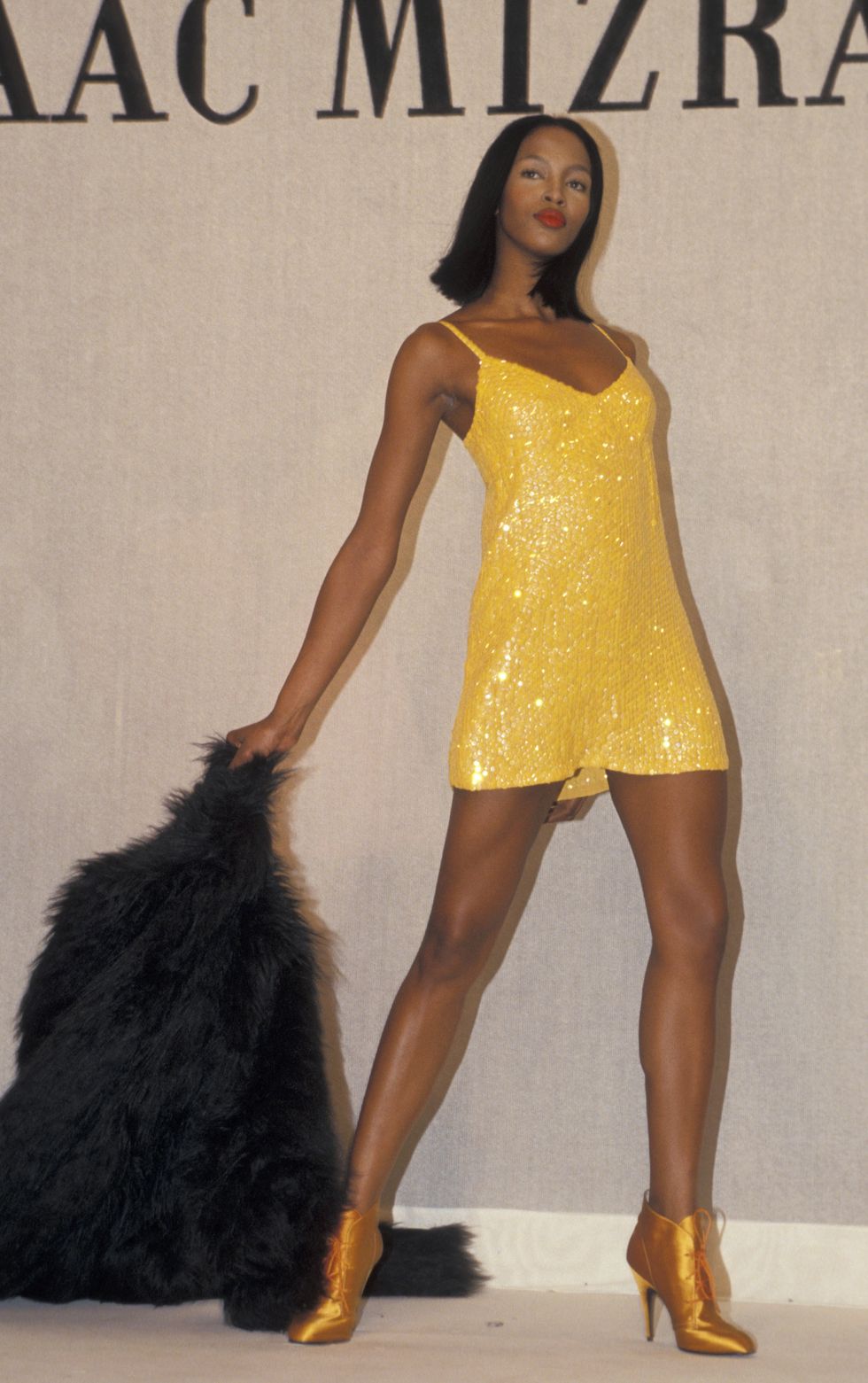

Naomi Campbell at NYFW Fall 1994

So I want to go back to the late '80s, early '90s. You were a young gay man who was coming up in the midst of the AIDS crisis. And I'm wondering what impact that had on you, to be having your career blossom at a time in which your community was suffering so much.

It was very rich with a variety of feelings. I have to say they were very, very separate thoughts. There was my career as a fashion designer and then there were all the friends that were dying which was obviously very sad. And just because I lived through AIDS and I was an artist at the time doesn't mean my work was about AIDS. It was, because it's who I am and you can't get away from it, right? It can't be separated out, but it wasn't specifically about AIDS.

What are your thoughts on the current status of the LGBTQ+ liberation movement?

I've always loved being gay, not just 'cause I love dick. But because I just love being gay. I used to love going to secret little places like these cocktail parties that happened in the early '80s, they were called Boy's Night or Boy Parties or something. And they were happening at Columbia and it was like, "Oh my God, we're like going to like a gay dance at Columbia. Like, pinch me."

And there was something incredible about walking into like Uncle Charlie's, which was this gay bar on Greenwich Avenue, or Cahoots or something on the Upper West Side, and you were gay in a gay bar. It was the greatest thing in the world. Now I don't think there's that kind of solidarity between LGBTQ+ people. And I think that's as it should be. I believe in evolution. But there was something extremely fun about that. And as much as I miss it, I don't regret for a second that this dialogue has become bigger and more charged, more politically charged. I'm for it. You know, I believe in what I believe in. But I'm so excited by a young generation who tells me new stuff about how they want to be perceived. And so hooray for LGBTQ+ fights, because that's the only way you move forward.

What about the current state of fashion? How are you feeling about it?

When we made Unzipped, I wanted there to be some kind of vehicle that explained how for me, surprise was the number one element of fashion. I still love surprise, and now I just hate fashion. I just hate it. I think it's the worst. And it's partially what it's become. It's just become this kind of clown sideshow thing. No, really, I mean this, I'm just going to say it to you, because there's no surprise to it at all.

And there's no actual thing going on. Even the greatest show in the world is a bunch of skirts and sweaters and a lot of styling. I don't mind if that sounds bitter, because I think maybe that'll help people doing it to make it better. I don't know what came over me all those years ago to actually care so much about it. I'm sorry. That's just where I am with it. That's something that we have to talk about for one second because for my generation — which is not the baby boomers and it's not generation X exactly, it's right in the middle between boomers and X — there was something about the necessity of everything being extremely smart first, right? You had to be extremely smart and then visually it had to be great and then it had to be this and that, but above all it had to be inventive and fresh and a surprise, right? And somehow now it doesn't have to be smart at all.

Of the big gun models from that era, who do you keep in touch with today?

None. Except Veronica [Webb]. Veronica and I are really good friends. Um, you know, I follow some people on Instagram. I follow Shalom [Harlow] on Instagram. Shalom and I are friends but we don't see each other all the time, whereas I see Veronica on a regular basis. [Long pause] I recently spoke with Josie Borain over Instagram. But that's about it.

Do you read Vogue today?

No, no. I honestly never really read Vogue. Well, I read it when I was a kid. I was mad for it. I poured over every page and then I worked for different people where I had to read it 'cause it was Vogue. When I started on my own, I tried to keep in touch with it, but then I just couldn't, because if you look at it, it will throw you off. It's a real psychic kind of very big, depressing thing.

Favorite memory from filming a guest spot on Sex and the City?

Seeing Sarah Jessica Parker's bra tree. She had this insane bra hanger thing that was just masses of bras. Because I love tits!

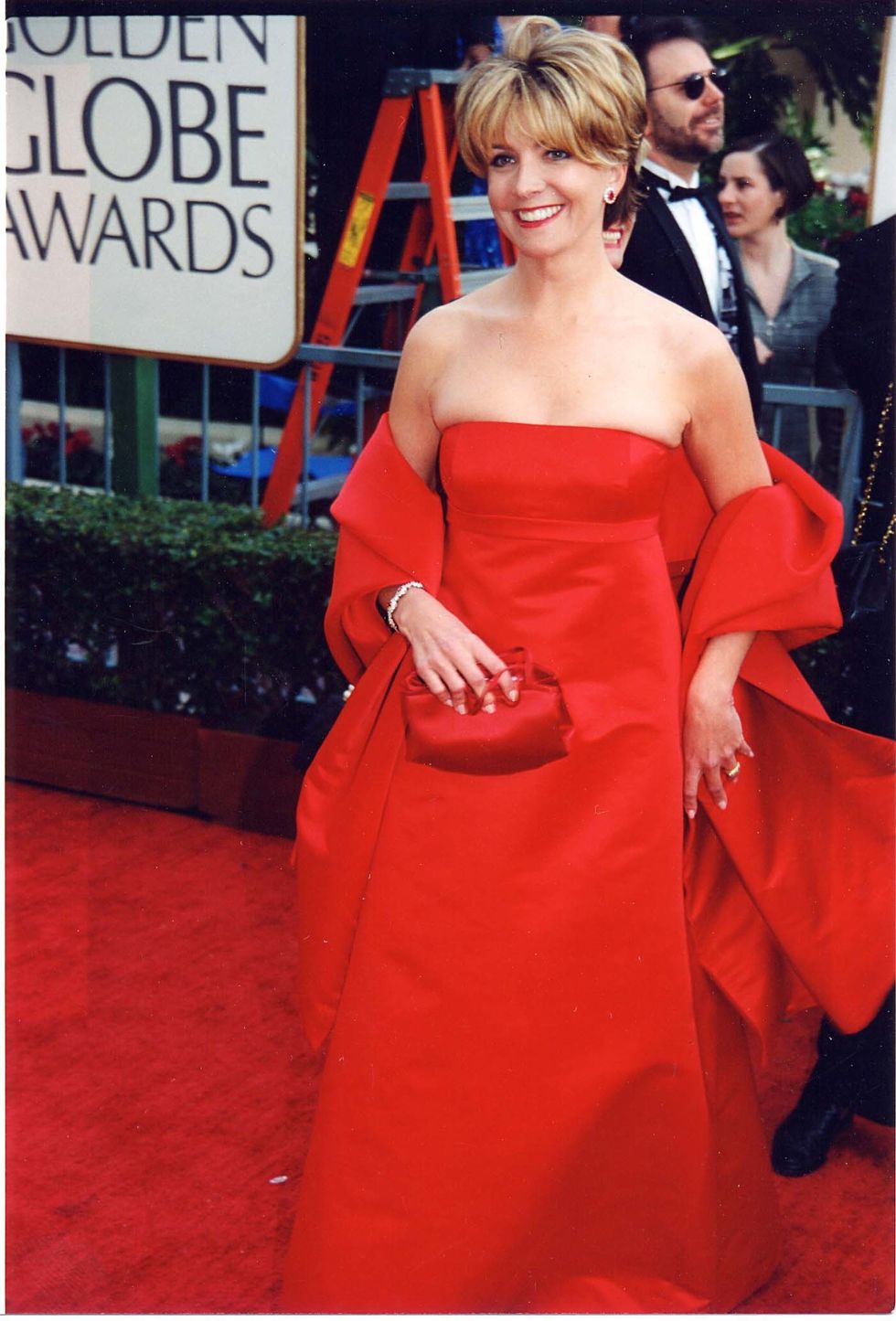

Natasha Richardson at the 1997 Golden Globes

Favorite celebrity you've ever dressed?

Arnold, my husband, recently came across this picture of Natasha Richardson from the Golden Globes from like 1997 or something. And he sent me, it was like wow. Natasha. She was a great, a great person. I really loved her. And she was kind of a friend. And Liza! And Sandra!

Were you surprised by the pushback you received to your February endorsement of Mike Bloomberg?

I was very, very surprised by that, yes. I was very surprised by it and I'm not exactly sure where it came from. I suspect it was Bernie Sanders supporters, right? Because I don't think Republicans gave a shit at that point, right? Maybe it was some Republicans who were, but it was mostly people who loved Bernie Sanders. And you know, I love Bernie Sanders for a lot of reasons, but Mike Bloomberg is someone who I thought of as a leader. I was very, very surprised that people saw him in a different way because I don't. I don't see him as this vicious evil oligarch. I see him as this really smart guy who built this huge empire and made a lot of money. But he always uses it, I think, to a really good end. I think a really, really good end. And I know there are people on the LGBTQ+ spectrum that are going to say incredibly contrary things, but posterity will look back on Mike Bloomberg and say he really helped gay people of the world and the lesbians and the gender fluid people of the world. So they can blow back right now, but posterity will look back at him and know that he was a very good person.

Welcome to "Wear Me Out," a column by pop culture fiend Evan Ross Katz that takes a look at the week in celebrity dressing. From award shows and movie premieres to grocery store runs, he'll keep you up to date on what your favorite celebs have recently worn to the biggest and most inconsequential events.

Photography: Jason Frank Rothenberg

Archival photos via Getty

From Your Site Articles

- Nowstalgia: Marc Jacobs' Grunge Collection That Got Him Fired ... ›

- Ladyfag, Debi Mazar and Patricia Field on the 2019 Met Gala - PAPER ›

- The Most Bizarre, Bewildering Fashion Show Attendees - PAPER ›

- Joe Biden Calls Florida's "Don't Say Gay" Bill Hateful ›

- Isaac Mizrahi Is Returning to Café Carlyle in NYC for Part 2 ›

- Ladyfag, Debi Mazar and Patricia Field on the 2019 Met Gala ›

- Nowstalgia: Marc Jacobs' Grunge Collection That Got Him Fired ›

- The Most Bizarre, Bewildering Fashion Show Attendees ›

Related Articles Around the Web