LGBTQ

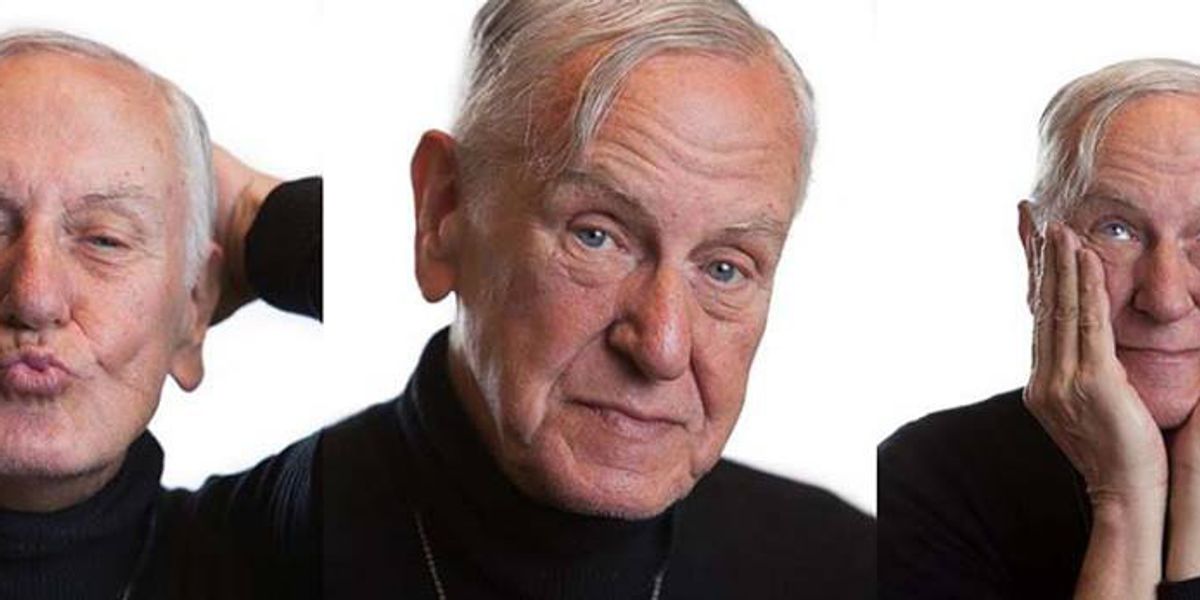

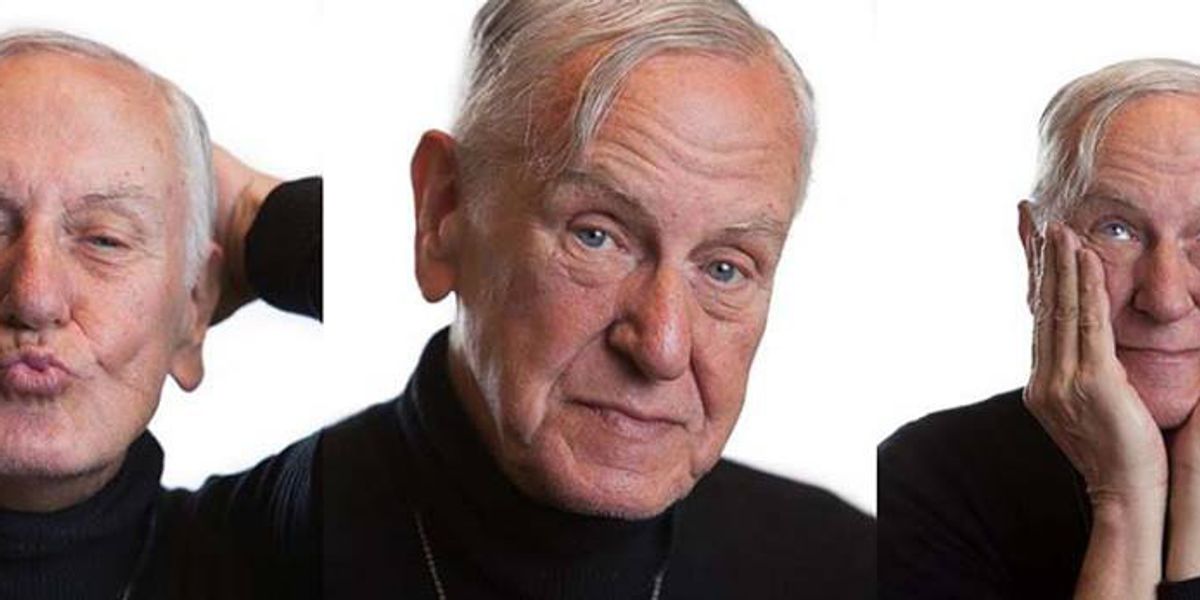

Historic Gay Playwright Robert Patrick on Surviving, Writing, and Being Grabbed by Shirley MacLaine

26 July 2017

At 80 years old, Robert Patrick is engaging in the same activities he did when he broke into playwriting in the 1960s—writing, performing, doing errands, and helping out. An innately creative soul, he's written over 60 plays, starting with The Haunted Host, which premiered in 1964 at the groundbreaking Caffe Cino in the Village, and leading to 1973's Kennedy's Children, which takes place in the East Village bar/restaurant Phebe's, which he filled with shattered dreams and clinging hopes. Robert archives memorabilia related to Caffe Cino while staying in the game in L.A., where he's lived for 25 years.

Hello, Robert. How long does it take you to write your plays?

Anywhere from a day to a year.

What have been the easiest ones to write?

When Joe Cino [Caffe Cino owner] or Ellen Stewart [creator of La Mama Theater] or Tony Bastiano [off-off-Broadway entrepreneur] would say, "The show that was supposed to come in didn't come in. Can you get something up?" So I'd write it, get some actors, and get it in.

Describe Caffe Cino.

It was the off-off-Broadway of modern theater, of gay theater. It was the fountainhead of everything.

How did you end up there?

I followed a pretty boy in. His name was Johnny Dodd. I was walking down the street. It was my first half hour in Manhattan, from New Mexico. I followed this pretty boy who had long hair and was selling jewelry. He turned into Caffe Cino, and it turned out to be the wellspring of 20th century theater. He turned out to be a lighting designer.

It was such a wonderful place. It was like being in Paris when the impressionist painters all got together, or in Hollywood when they all got together and made the movie studios. The joy of being there! I took a typing job a few blocks away so I could run to Cino every day after work and say, "What do you need?" I would shop or mop or wait tables, anything they needed. They were the most extraordinary group of people. I've just been commissioned to write a play about Cino. We knew we were doing something great, but the main reason was it was great to be with each other. The other playwrights included Lanford Wilson, Sam Shepard, Paul Foster, and William M. Hoffman.

But Sam Shepard didn't write gay plays, did he?

No, it wasn't just a gay theater.

What was it like to be a gay playwright in the 1960s?

It was practically unique. It was hell being smart or gay or an artist in the 1950s. All of us, as soon as we could, got out of America and went to New York, which was, believe me, a different country. A place like the Cino was glad to have you be gay and smart and artistic. It was largely gay. It was like being in your own production of All About Eve. We did it all for free—nobody got paid except, I think, the waiters and dishwashers—and that was one reason we could experiment. We didn't have to please anybody. We didn't have to worry about drawing an audience or pleasing the critics. We did theater in places that made their living from something else, like bars and bookstores. For the first time, theater could be an independent, non commercial, expressive art form. Lanford Wilson and I were roommates. When he wrote his first play, I helped move in the scenery for it. Watching the director and the stage manager fold and unfold the sofa, I had an idea for a play about two men unfolding a sofa!

Did you ever have a rivalry with Lanford?

No. We all loved each other a lot. When Lanford began to get famous, a smart antiques dealer in the Village saw that he was gonna be something big and offered to buy his correspondence, and Lanford told the man that he should buy mine and Sam Shepard's correspondence too. When I brought my first play to the Cino, I handed my play to Joe and Joe threw it into the garbage. He said, "You don't want to be a playwright. They're terrible people. You'll thank me one day." But Lanford said, "If you don't do Bob's play, none of us will do any plays here ever again." Joe said, "Oh, a palace rebellion," took my play out of the garbage and dusted it off. Lanford did the first gay play, The Madness of Lady Bright, and I did the second, The Haunted Host.

Were Joe Cino and Ellen Stewart mutually supportive?

Yes! On her deathbed, Ellen said the only thing she regretted was not having taken over the Cino after Joe died. I assured her that she had kept it going because La Mama was the Cino and all the off Broadway around the world are the Cino, and none of them would have existed without Ellen's example. He was La Papa and she was La Mama. She was a survivor and he wasn't.

When Kennedy's Children made it, did you feel any guilt about being successful?

Oh, no. I didn't take it seriously. I already had so many friends swept away into that world—Lanford and Paul Foster and Sam and Bill Hoffman.

Had you been feeling, "When is it my turn already?"?

I was only concerned with an unhappy love affair I was having. I was not good at being a success. I blew all the wonderful opportunities it brought. I sold the rights to Kennedy's Children outright.

Do you regret that?

Financially, I regret it.

How much did that cost you?

A lot.

Would you like to be back on Broadway?

If I did, I would handle it better now

What would you do differently?

I would hang around more. I wouldn't let them cast movie stars in the replacement company.

You weren't happy with the casting?

I wasn't happy with the replacement company. I was blissful with the original company.

I'll have to look up who you're talking about.

Shelley Winters. She only did it in Chicago. She told the cast they didn't have to learn lines, just improvise.

Why did Kennedy's Children resonate so much, aside from the subject matter?

I think largely because of a man named Don Parker, who insisted on getting it produced. To me, it was just one more of my plays. Don wanted to play a part, so he optioned it from me, and for three years went all over the world trying to find someone to produce it. He finally found a bar in London who would do it. The next morning, I signed contracts for translations into 60 languages. [Eventually, the play moved to the West End and then to Broadway.] We saw every beautiful woman in New York for Carla. I flew [cult actress] Mary Woronov into New York. The director agreed she was perfect for the role, but he feared she was too strong for him to direct. He felt I should cast her and fire him. Shirley Knight called and said she was in America and did we want her for the play, as Carla--because we'd asked her in London and she turned us down—and we said yes. For Rona, the hippie girl that Kaiulani Lee played, we begged Lily Tomlin to do it, all sorts of people. Shirley MacLaine, who we'd asked to play Carla, grabbed me in the lobby of the theater and shook me--she actually hurt me--and said, "Why didn't you make me play Carla?" I got physically mistreated by more actors after that show opened!

Ooh. Tell me more of these stories.

Julie Newmar decided she wanted to play Carla. She started chasing me around Times Square saying, "Only I am Carla." Finally, one night, she tried to drag me into a taxi, the idea being to go home with her and "In the morning, you'll know I'm Carla." My boyfriend was pulling me out, and he won.

The boyfriend always wins. Any other memorable celebrity encounters?

Quentin Crisp is the best one. Shortly after he became famous on TV, he moved to New York, but I didn't know it. One day, I was walking down Second Avenue and I saw a circle of policemen. In the circle was Quentin. I thought he was in some trouble. He said, "Oh you're probably referring to these gentlemen here. Oh, no. This is America. They only want my autograph." My most memorable actor encounter, because he was my idol as a boy, was Sir John Gielgud. [Patrick met with Gielgud, who was interested in starring in his play, Judas.] Unfortunately, he took a movie—Arthur, for which he won the Academy Award. James Mason, Richard Burton, Tony Perkins, Jose Ferrer, and Mark Lenard all wanted to do it. They all got movies.

Does theater still have capacity to shock people?

Very much. Americans have never gotten used to there being live theaters since movies came around--they're so enthralled by the aliveness of it. I've become a performer. It's been discovered that I can sing. All of sudden, people are driving 50 miles and buying tickets to hear me sing. If I knew I could sing when I was 12, I wouldn't do anything else. Bars in L.A. put on shows like Planet Queer, and Gay DD. I'm writing a song about Donald Trump. I write my songs and I sing a cappella. I'm getting itchy to do another solo show. I might call it The Thing from Planet Earth. My first show was What Doesn't Kill Me Makes a Great Story Later and then I did Bob Capella. The third was called New Songs for Old Movies. I did songs I'd write for Fred Astaire, Barbra Streisand, Carmen Miranda…

You're inspiring. Thanks for the chat, Robert.

Splash photo by Diana Ludin.