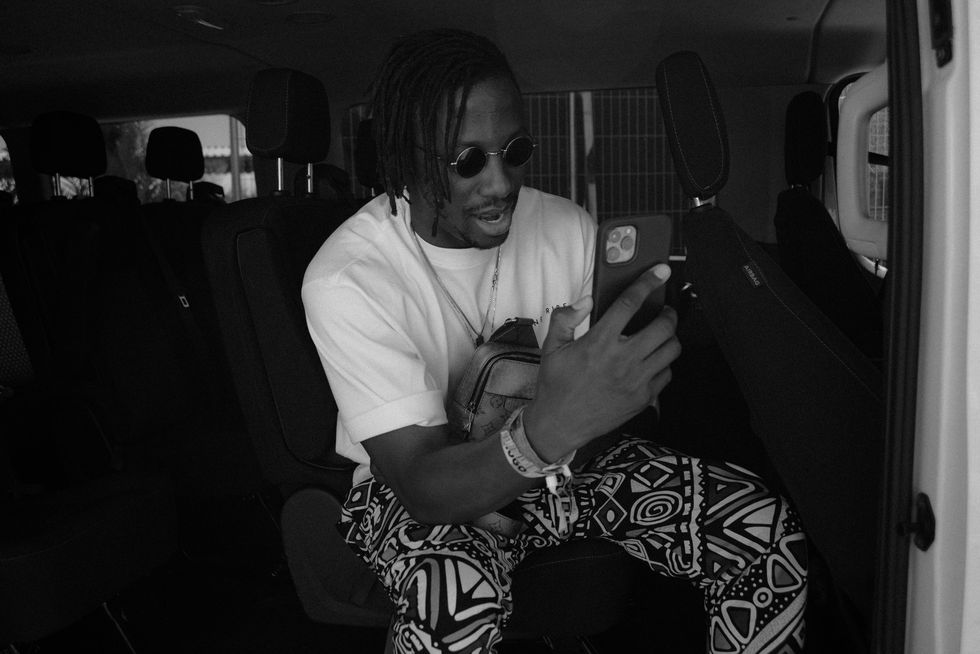

AMÉMÉ is building himself a “house.” Already looking 10 steps ahead of where his career stands now, the rising producer has sights much bigger than his debut DJ set at Weekend One of Coachella. Just seven years ago, he was only a guest at the California festival and now we’re sitting in his own private trailer, so it’s safe to say this headspace works wonders for him.

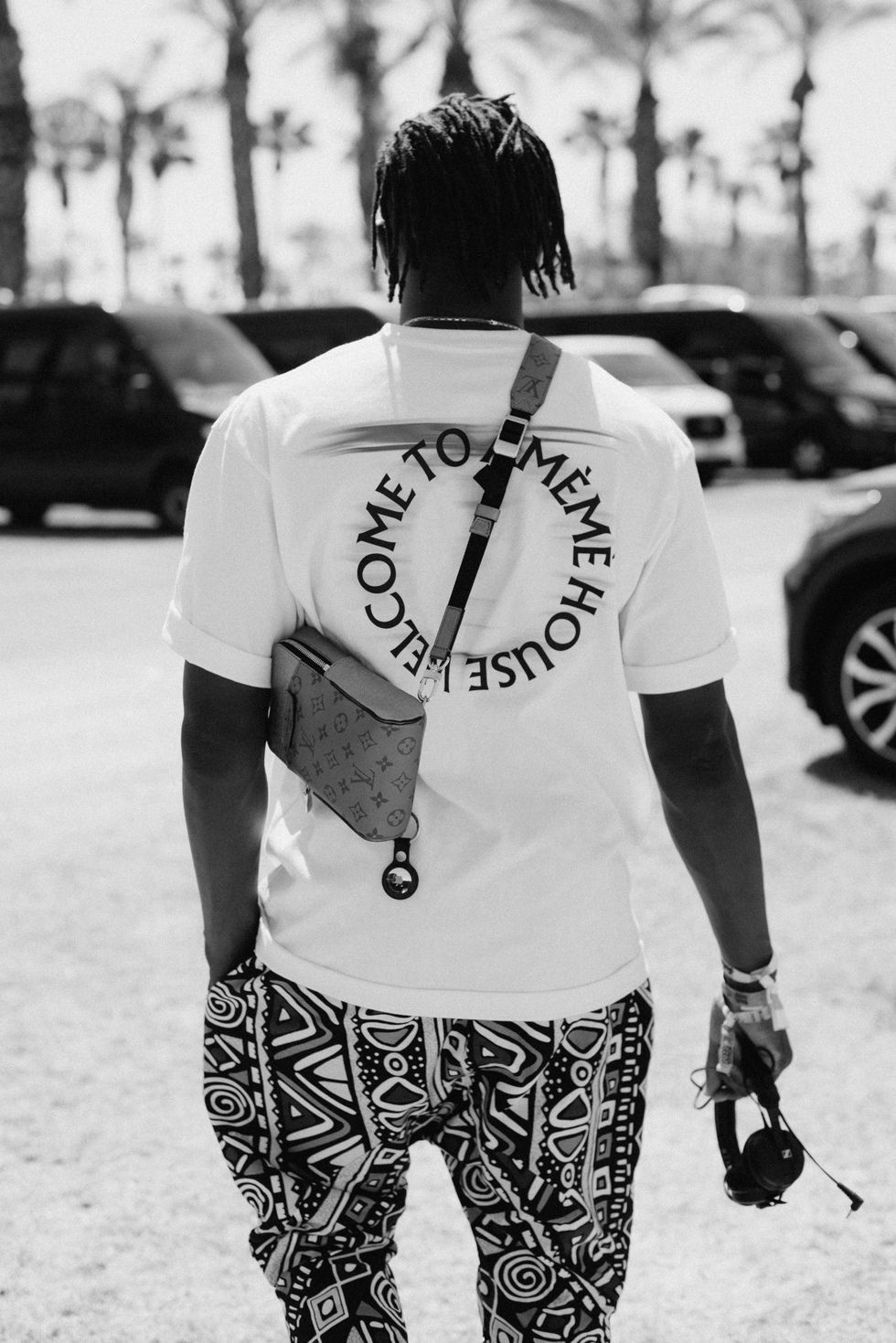

“It’s going to be a whole show,” he predicts, eyes lighting up and hands forming grand shapes when asked about his t-shirt that reads, “Welcome to AMÉMÉ House.” Like “Lion King on Broadway,” he pictures his current club show with more “crazy lighting” and “people singing” — an “audiovisual experience” where he’ll be “jumping around and on drums.”

Satisfied with his manifestation, AMÉMÉ sits back into the trailer couch. “That’s my end goal,” he smiles. “I always want to do it better and better. At some point I’ll be like, ‘This DJ stuff... what’s next?’ And I’m already thinking about it.”

Real name Hubert Ameme Sodoganji, 33-year-old AMÉMÉ was born and raised in West Africa, before moving to New York City with the goal of becoming a doctor. But even in the midst of pre-med schooling for three years, he was quietly mapping out his next move: a self-taught transition into music, where he’d build off his worldly references — from Berlin to Benin — and wield a new sound inside the Afro-House genre.

With consistent support from the 2022 Grammy award-winning Black Coffee, AMÉMÉ has managed to quickly rise up the industry ranks. Earlier this month, he released “Wait No More” off Save Records, a magnetic cut that brings together tribal drums and Afro groove for a taste of what’s to come from his next EP, out later this year. “I don’t wanna wait no more,” he repeats with pitched down vocals — a mission statement for an artist who moves with urgency.

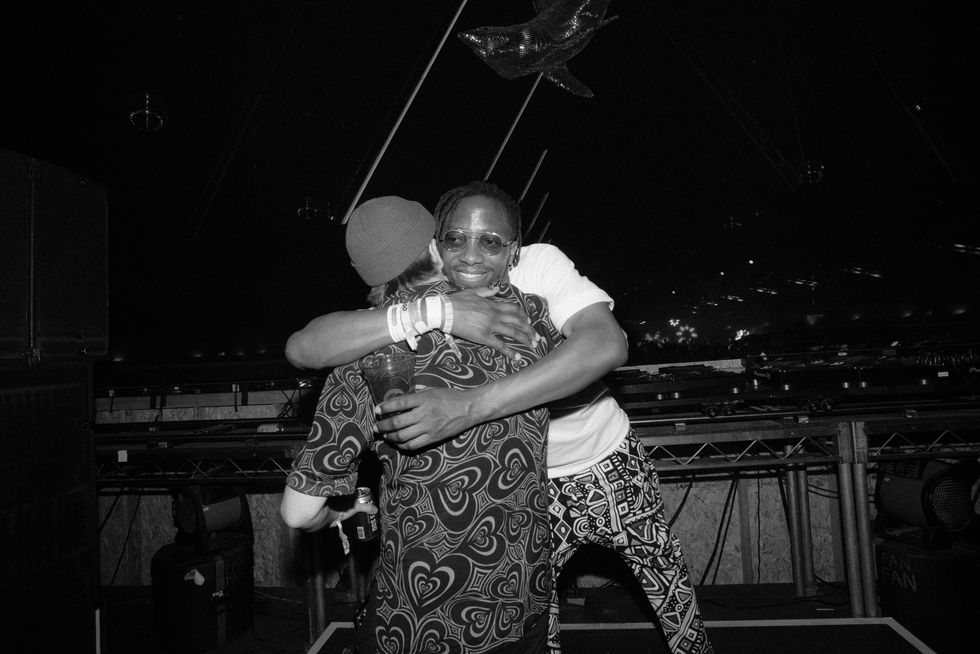

AMÉMÉ’s DJ set opened Coachella on Sunday inside the Yuma Tent, which has played host to underground sounds since 2013. As the third and final day of the festival’s first weekend, only diehards stopped by, which gave AMÉMÉ the freedom to experiment. “I went totally off-route,” he says afterwards. “The last track I played was supposed to be the third track. You have to think about the crowd once they’re in motion; they throw back what you give them.” He also snuck in demos of his own, saying, “I never release a track without testing it out live.”

Despite this being a massive feat few DJs achieve in their lifetime, AMÉMÉ isn’t soaking in the glory of his breakout appearance. “I’m already like, ‘Next time I’m coming back and I’m coming back like this,’” he says, pointing again to the words on his tee while recognizing that his constant projections are challenging for many to understand or relate to. “There’s one stage I really want to play: The Sahara. I would crush the set.”

After dusting himself off from the Coachella desert, AMÉMÉ tells PAPER a little bit more about himself. Get to know the artist before he blows up (and eventually books The Sahara stage), below.

How are you feeling?

I’m feeling grateful, overwhelmed, excited.

It’s weird being back to a festival of this scale after taking some time away. Making dance music, especially, is so much about the people, connections and being in the real world. What did you learn from the last few years without all that?

The first thing I learned, as humans, is that we’ve always adapted. Human beings, no matter what, find a way to prevail and find peace with it. At some point when COVID came along, all those livestream sets became a thing. At the beginning, I was like,”Livestream, who's going to watch this?” But that helped expose me to a bigger audience. What that taught me was that, in any situation, there’s always a way to get there.

Did it shift your creativity or how the latest music actually sounds?

One hundred percent. I’m coming from being on the road all the time and being distracted in cities like New York or Berlin — cities that are super vibrant. So I got a lot of time to focus on music, but also myself. For a while, one of my main challenges was being very comfortable with a lot of different styles. I grew up in West Africa and listened to a lot of rock music. In the electronic world, being in New York and Berlin and having the German techno aspect, the underground Brooklyn sound was challenging at times. But in that pause that I got, I was really able to sit down and think about it: “This is my origin, this is what I’m related to, but this is the sound that I want, this is what I reflect and create my own spectrum. It honestly helped me a lot.

Is there a sound that you fall back on the most? Having grown up in West Africa, do you consider that your foundation?

Afro-music, percussive music, drums is the essence of my music. I made this shirt, “Welcome to AMÉMÉ House.” Obviously, you can take it as House [music], but thinking about the music I produce and in a set, I get to navigate from Afro-House to Afro-tech, jungle-tech, but one thing you’ll find along the way is percussion, the groove. And that’s my origins in Africa, it’s the bass.

What do you remember most about moving from West Africa to New York?

Two years before I moved to New York, I came twice in a row. My aunt was living in New York, and I would come and chill with her. I knew how to move around the trains, so when I came back it was like, “Rock and roll, let’s go.” I’m super glad my mom allowed me to get my feet in the water before moving. Still, that unlimited freedom that I got from moving there; my parents are very controlling like, “You have to go to school and study biology, chemistry,” and I came to New York to become a doctor.

But I got to New York and did what I wanted. That really shifted me because of the music scene. I went to an English school for a year, and this girl would come into the class and be like, “Yo, you seem cool. I’m going to invite you to this club.” I had never been to a club in New York and she invited me to Pink Elephant. Back then, nobody could get in. At that moment, it exposed me to electronic music more and I was, “This is crazy.”

I love that you were pre-med. Were you actually studying to be a doctor?

In West Africa, in the last three years of school, you have to specialize. If you’re going into medicine, you have to do chemistry, biology and math, and that’s what I did. When I came to New York I was bored of it because I came from West Africa.

How did your studies impact the way you approach music, if at all?

Weirdly, I’ve always been able to compartmentalize things. It doesn’t impact the way I make music, but it does impact the way I make decisions. Once I realized medicine wasn’t for me, I was like, “Shit, I still have to get a degree,” because my parents spent too much money for me to be here, so I had to figure this out. I moved to finance, like, “Okay, finance guy who wears a suit and parties,” so I did that and worked at a bank for seven years. I was DJing for the last 10 years, but I was a banker by day. Science, business and my cultural background, like our ceremonies and the musicality of it, and being in musical theater as a kid, gave me the perspective to wait for nobody and always do it the way I want it.

When I first went to New York, people were like, “This is too soft, there’s way too much drums,” and I was like, “Okay.” I was playing all the shitty bars and moved my way around it, but then I was like, “I want to start my own party.” So I had to go to the best clubs. I found two clubs that I really wanted to play; the same challenges I had when I went to Berlin. I sent my music to every label and nobody wanted to sign me, so I was like, “I'm going to start my own music label.” That academic and my background, my parents’ resilience, gave me that. I don’t wait for nobody. Even my team knows that.

Being an artist, especially starting out, you have to have that business mind and projection of early success. When no one is giving you opportunities, you have to forge it.

I’ve seen so many talented people, but like–

The most successful people aren’t necessarily the most talented people.

100 percent. The thing about me is that I’m really good, but on top of that I have resilience that makes me go for it and I will not stop until I get it.

House, as a genre, has this super rich history. How much of that interests you?

Everyone has their own goal. For me, history and background is not it, but what I’m bringing is the progression of that story: An African kid that didn’t grow up with House music, then having Afro-House in Africa, then going to New York and going to Berlin, and then all those together show how the world is a big and, at the same time, small place. We’re more connected than we think. Also, hopefully I can be a representation for other people, being an African Black DJ in this massive industry. We have Black Coffee, another African DJ, but who else? I’m excited that other people can see, “I can do it too,” and this is the piece that I’m bringing to the story.

Why do you think there hasn’t been more people like you in this space?

The world we live in. I always like to stay away from pointing fingers, I like to stay with solutions.

That’s the pre-med mindset.

Yeah. The reality is that House music came from Black people. It went to Europe and it was more accepted there, but throughout time the name got lost. If you go through America, some Black people don’t know about House and they’re like, “That’s white people stuff.” Again, I'm not pointing fingers at anybody, but I’m hoping in the near future there’s people from my culture, Black culture, that are like. “Wow, this came from Black culture.” It was America, but there wasn’t enough time for it or enough resources, so then it went to Europe and things started to happen. I can see how through time it got lost in space, but we’re bringing it back.

Whose voice is on your new single, “Wait No More”?

A lot of my tracks, I work with co-producers or engineers, and when I started the project it was my voice. I had a groove, a bassline. When I was in the studio with my friend Neil, he’s a British guy with a rocky voice, I was like, “I’m trying to find and write vocals for it.” We knew we were going to use a plug-in to change the component of the vocal. That voice is not natural, it’s a plug-in, but when he started singing his voice was so heavy and it sounded smooth. It wasn’t too far away from the plug-in, so it applied automatically.

In the future, do you think about putting your voice on more tracks?

Yeah, “No Justice No Peace” was made during Black Lives Matter, and I was going to a protest and I rapped in the song. I have a lot of tracks with my voice in it. I was in a rap band as a kid. When I was younger, I didn’t have many friends but I had my music. Me and my brother and two other siblings started a rap band, there were four of us, and we were rapping in French.

How long did you guys do that?

Like three years. We did national competitions.

At what point in the production process are you like, “I’ll add my vocals to this”?

It depends on what the track is for. The track that I'm like, “This is going to be for German nights in Berlin, on the ground kicking ass,” I’m like, “No vocals, this is going to be fine.” The intention of the track is also important.

It sounds like you pay attention to the audience and how they’ll experience it. Separately, Voodoo is an integral piece of your life and work, right?

Voodoo is a national thing for us, Voodoo comes from Benin. Anything that the West does not understand they always try to lean towards the negative, like black magic does exist. Voodoo is energy, Voodoo is a religion in Benin that is used to heal and connect with nature. You have wind, water, the sea, there’s a lot of natural elements involved. But at the same time, since it’s energy, it can be used for violence. Like any religion, it can be used for good and it can bring peace, but it can also be used for crazy stuff. In Benin, Voodoo is normal. I wasn’t raised in a Voodoo community because my dad is Catholic and my mom is Protestant and I went to a Catholic school, but my extended family is from the village so they practice those rituals. I’ve seen stuff that I can’t explain.

Is this something you think about in your everyday life? This spirituality?

Honestly, I'm very connected to things; I feel things, I see things. When I want to do something, I put my attention toward it. I’m very connected to my higher self. It’s not Voodoo, it’s a more spiritual thing. I truly think there is a higher energy out there, and we may all speak in different languages but speak of the same thing. I live in New York and I meet so many people. Benin also prepared me for that. Coming to New York you have Muslim people, you have Christian people, you have Hindu people and everybody is together.

For curating a set like today, what is that process for you?

Funny enough, I never make a playlist, but I was like, “It’s Coachella, I have to have a vibe ready.” So what I did was have a direction. Ninety percent of the music is mine because it's Coachella. Where else are you going to display your art to the best of the best?

Are you responding to the room at all?

This is why I don't come in with a playlist. If you come in with a set idea, the crowd may not be at that level so then you’re stuck. The one thing for sure that I can say is that my music is progressive. It will go with the energy. The crowd is going to build up slowly and I'm going to take them on that musical journey. I’m going to start them with the melodic vibes we love, the cowbells, the percussion, the drums, that’s always the base. Then by the end, you’re going to get more angelic and hopefully get them for the next DJ.

Photography: Larsen Sotelo

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web