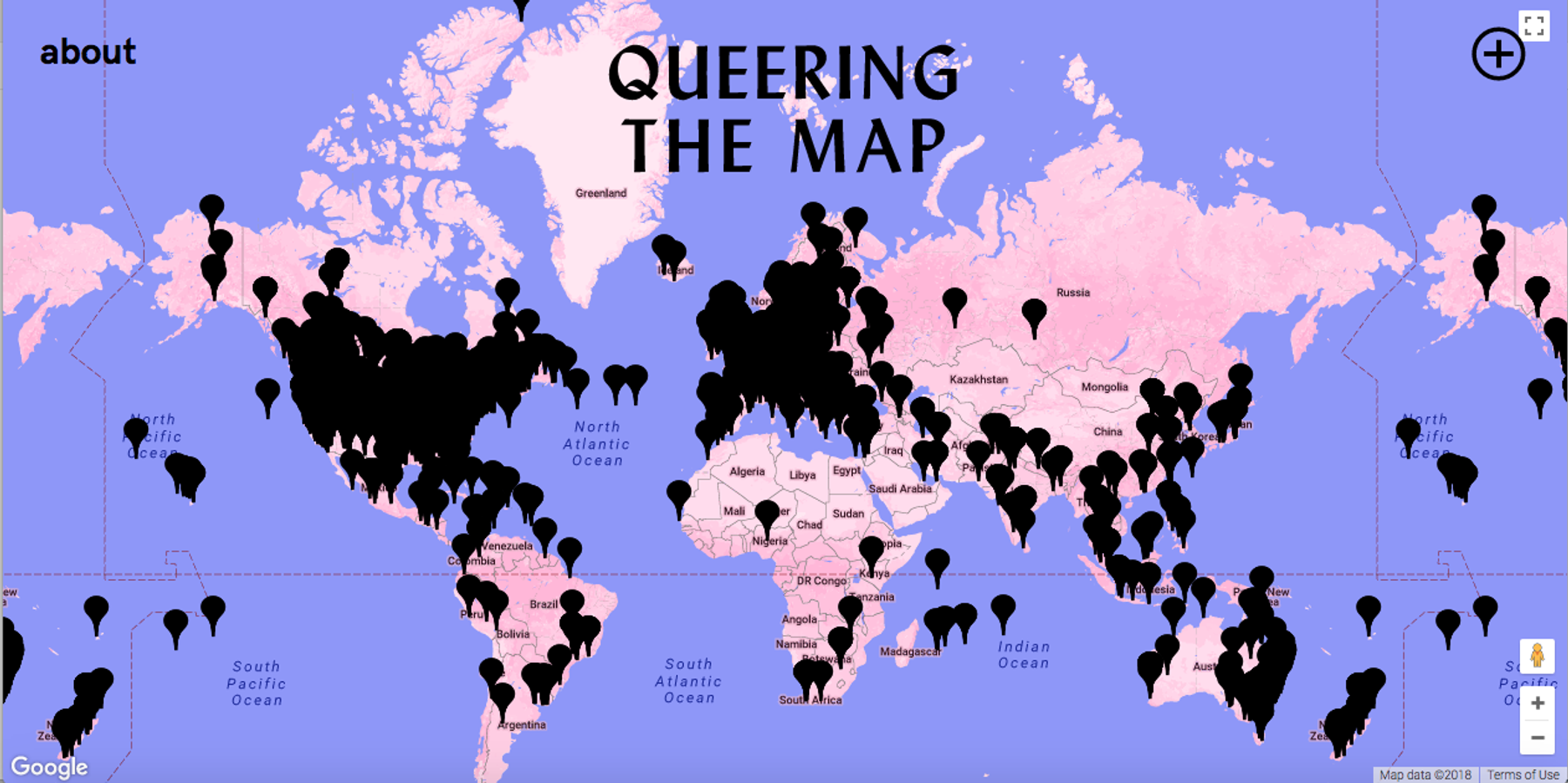

If you haven't heard about Queering the Map, it's probably because the project was halted just as it heightened — for nearly a month now, the initiative has been offline, shut down by Trump supporters who spammed the site into oblivion. But creator Lucas LaRochelle says Queering the Map will return soon — likely this week.

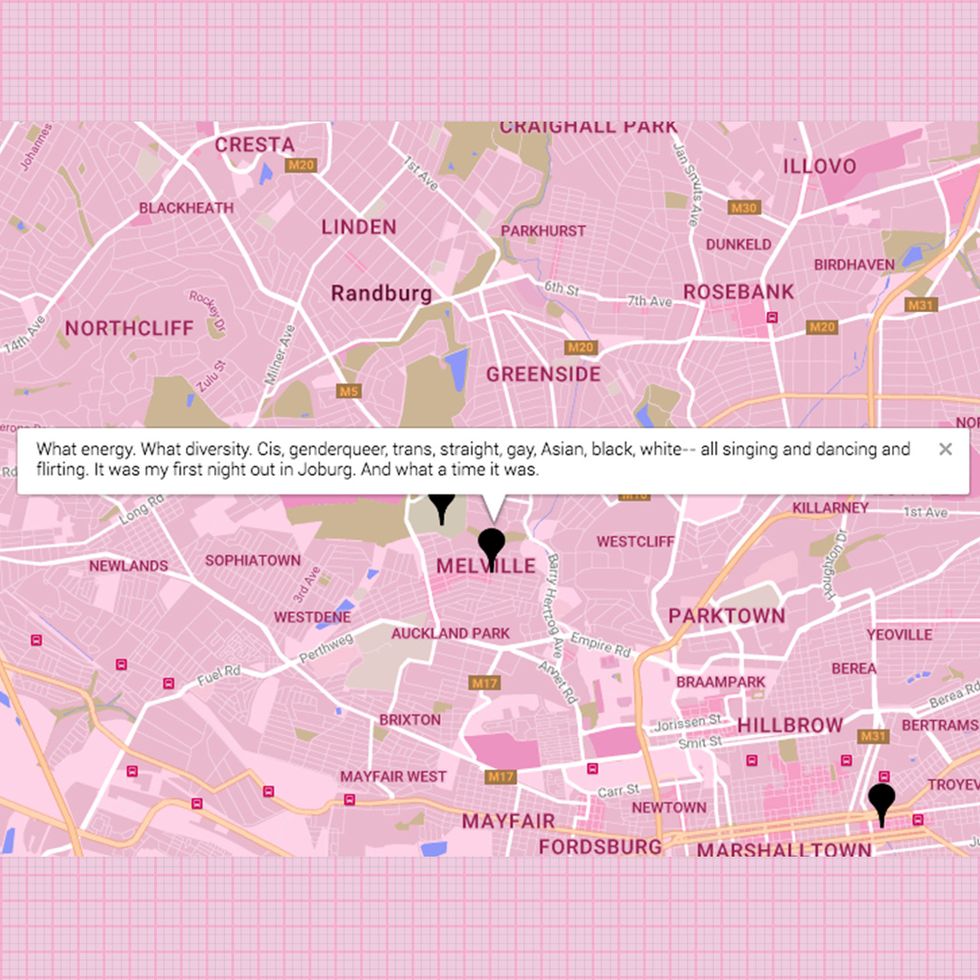

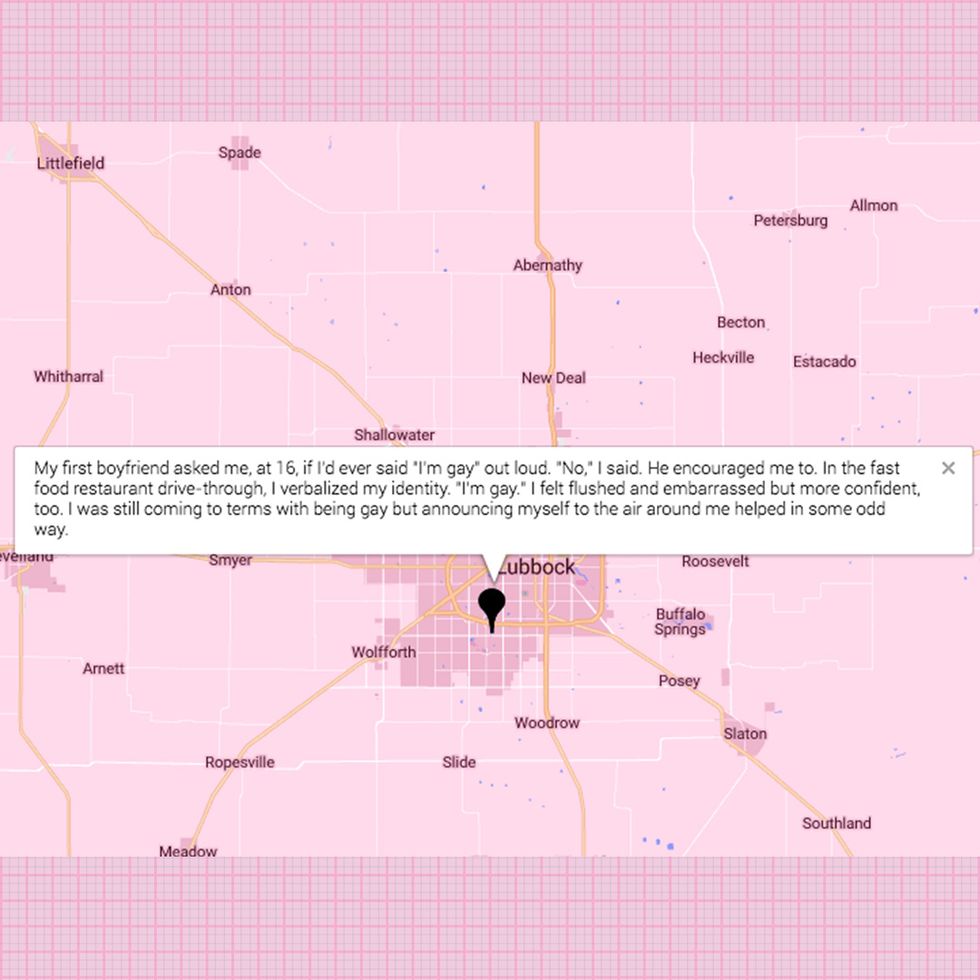

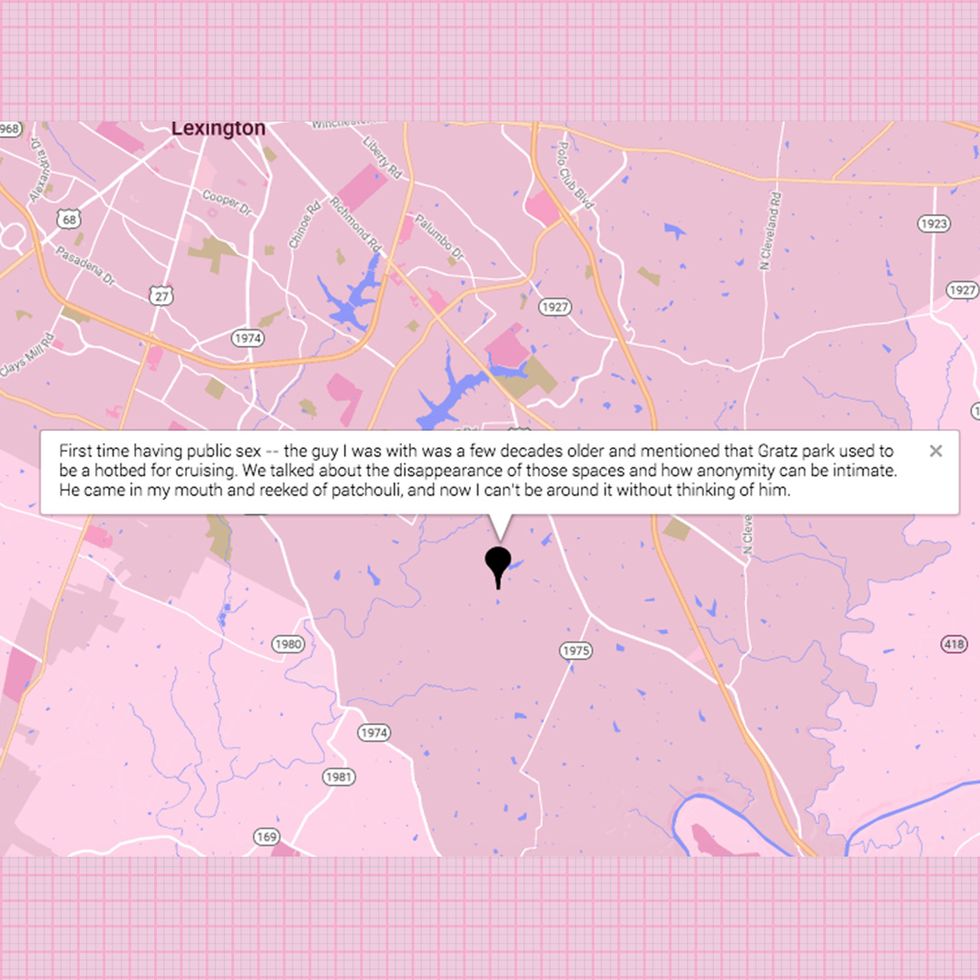

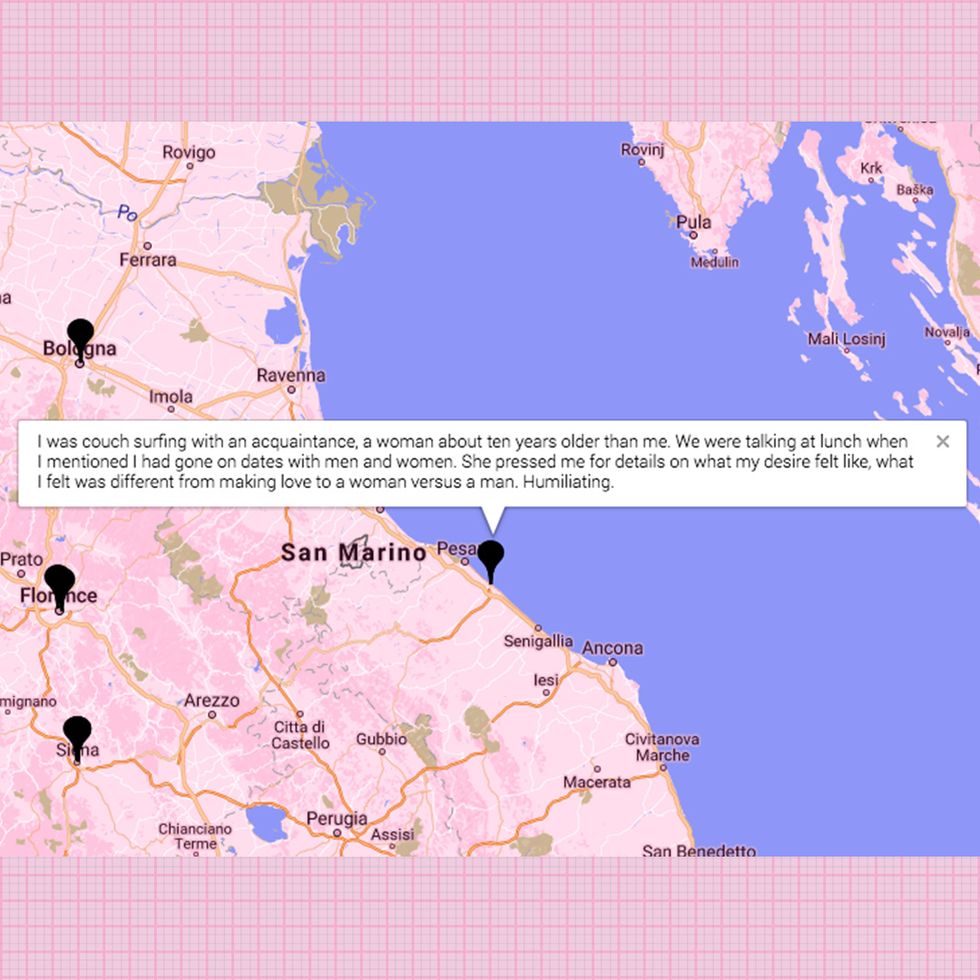

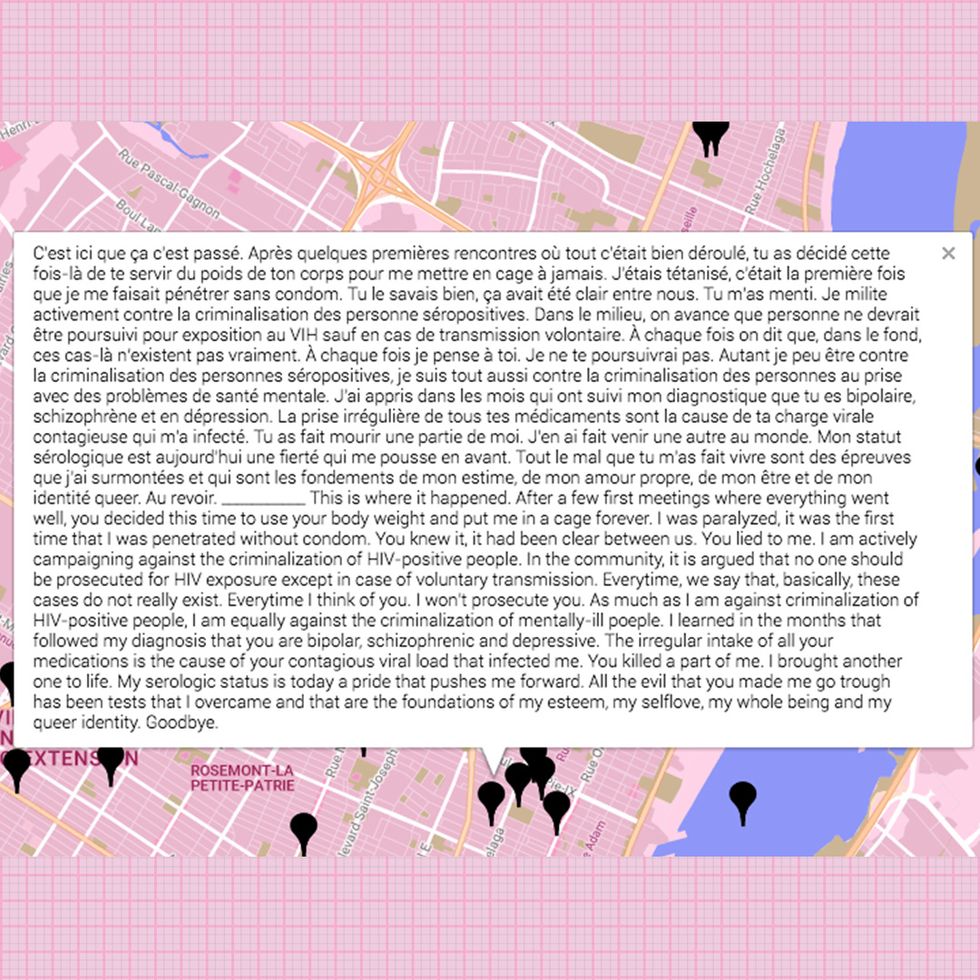

For everyone who missed its original incarnation, the site is an interactive means of documenting queer histories, crowdsourced by anonymous users who drop pins on a map and leave personal accounts with each. Recovered from the pre-spam life (and relaunching with the new-and-improved site) is a trove of intimate stories about coming out, of loss and heartbreak, about surviving homophobia, of trans visibility, epiphanies of sexuality, and even wistful missed connections.

In the span of three days in early February, pins on the map jumped from 600 to more than 5,000. It was "pretty wild" to watch unfold, says Montreal-based LaRochelle, who created the map about a year ago as part of a class project at Concordia University and continued developing it after. Pins had been growing steadily in the six months prior, but the sudden boom — "It went from 300 shares on Facebook to 10,000." — was unexpected. The site wasn't exactly equipped for a viral explosion, and homophobic trolls capitalized on that weakness, clogging the east coast United States with mass repeats of pro-Trump messages.

LaRochelle was quick to set up socials for the project (Facebook, Instagram) in the wake of the shutdown, through which they've since highlighted handfuls of saved posts, but began by calling for coders who could help beef up protection from spammers and hackers.

"The most important thing is making sure that once it goes back online, that it's fool-proof," LaRochelle says, adding that a moderator panel has been implemented as part of the new security measures. Now that it's supported with the behind-the-scenes work of "super dedicated" coders, Queering the Map, initially only collaborative on the front-end, is "now entirely collaborative and community generated, through and through."

That folks were so quick to rush in to restore and revamp the site, as well as the spike in submissions, speaks to how powerful the project is as a digital space for queers to see themselves, to feel represented, to know they're not alone, by reading someone's intimate reminiscing of their teenage first love in Montreal, back when the world was against them; a trans person from a family of Egyptian refugees dropping a pin in their hometown for visibility; a coming out story that starts with family rejection but follows through to a year-and-a-half later in Alaska, when they're ready to let go of that pain — a personal triumph.

The stories are often beautifully poetic, like a person recalling a time in love, but in hiding, who professes a devotion that'll last "until we are both nothing but sand in clams." Others are brief and simple: In Dubai, they learned to draw and, at the recommendation of their very first girl crush, learned to put on eyeliner, too. However straightforward or elaborate, nuanced or not, there is rich profundity in each.

"I've been really blown away by all of the different ways in which it's been interpreted, from really devastating stories, to devastating stories that come out on a positive note, to raunchy sexual encounters, relational experiences with other people, singular experiences, whether they directly relate to spaces or not," LaRochelle says. "I guess I've just been really moved by the way that it's been taken up by people. And the kind of vulnerability that's being shared is really what moves me."

The project is a living queer history that's inclusive to multiple perspectives, LaRochelle says, through a platform that affords more agency in resisting a singular narrative that marginalizes and others. It'll likely be studied; a researcher in Toronto is interested in how the project relates to non-binary identity, and someone from UC Berkeley might draw from it data for a study on queer affect.

LaRochelle's own academics continue, but they've cleared their schedule enough to prioritize Queering the Map.

"The Internet very literally saved my life when I was a young queer person growing up in small-town Ontario," LaRochelle says. "And seeing queer people represent themselves on the internet, just by not having that connection in my real life, made it clear that we do exist."

The visibility that saved LaRochelle as a kid is reflected in the roots of Queering the Map; in these stories, someone may find validation, liberation, or hope. That power is undeniably already palpable, yet isn't even fully realized yet — there's plenty reason for emerging stronger and unshakably resilient.

"The amount of incredibly moving emails that I've received in the past little while thanking me for making the project, I mean, it's like, there's no way that I could [stop]," LaRochelle says. "Other emails I've received are people saying I'm sorry, sorry that you have to do this work. It doesn't feel like [work]. It just seems like such an obvious thing to do."

Photos Courtesy of Queering the Map