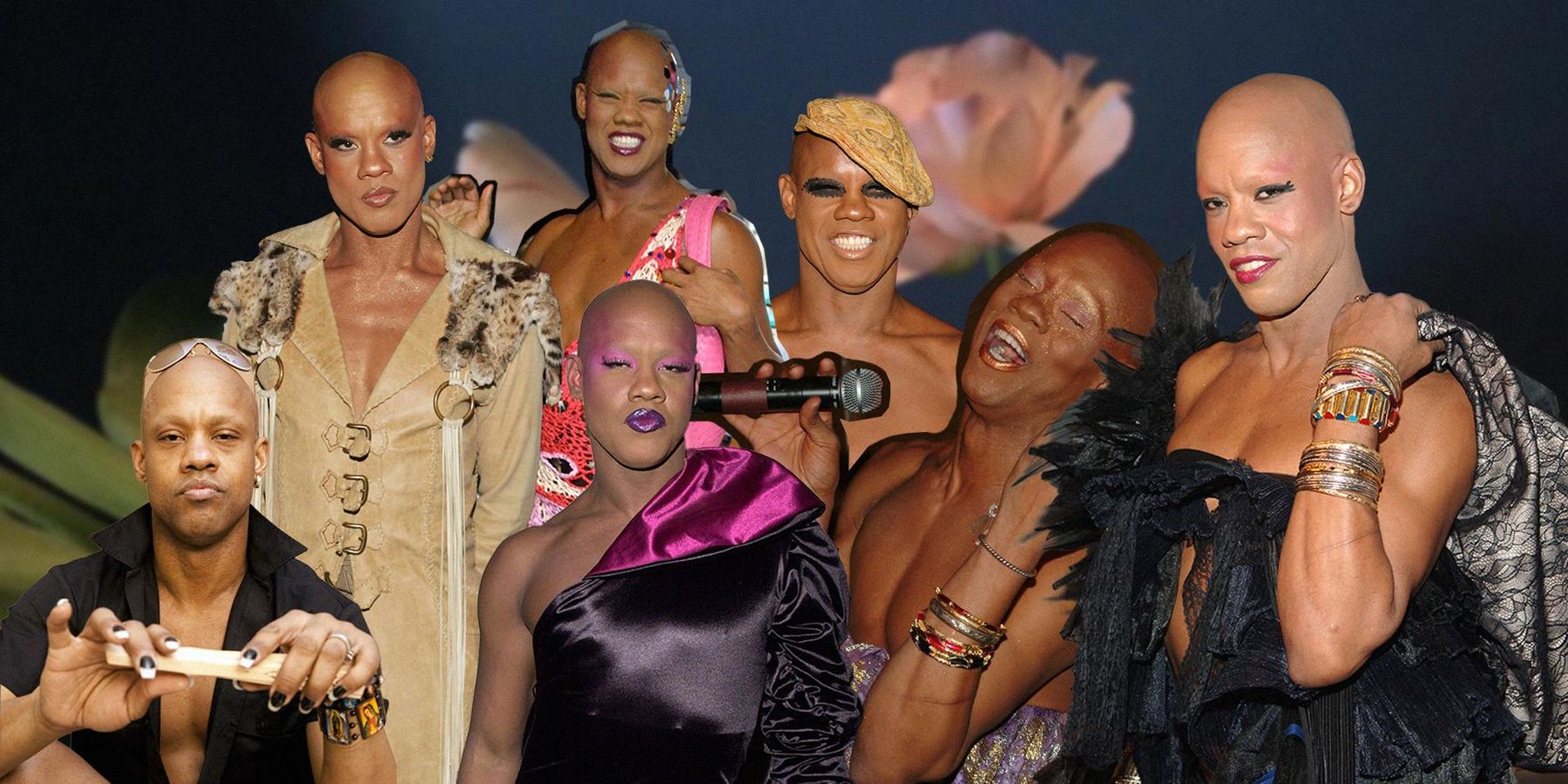

The first time I saw Kevin Aviance was at a children’s summer camp in upstate New York, watching him repeatedly yell the word “cunty” during a daytime pool party. It was an unusual booking for an underground techno festival like Sustain Release, but the normally calm crowd had broken out in dance, cheering as loud as they could for this tall, bald and bare-chested queen that had emerged from the pool in a pair of sky-high heels.

So despite only a few recognizing him at the beginning, by the time his electrifying set was over, everyone knew Aviance’s name — and that was exactly what he wanted.

“I love performing for people who haven't seen me before because you have to win them over. You know what I mean? I personally love that so much. It just lets me know that I can still do what I do,” the 53-year-old drag icon said, his voice softening with the realization that his career has finally come full circle after decades of work.

“I’m so blessed and so grateful that I’m allowed to experience the future... and see where the future of music is going,” Aviance continued, as I ask what it’s been like to witness his legacy influence a new generation of Black artists. He paused for a brief moment before humbly replying, “Well, I’m also influenced by them. I’ve been inspired by it all.”

After all, Aviance’s cultural impact cannot be denied. The “eldest daughter” of vogue-ballroom trailblazers, the House of Aviance, the New York nightlife legend rose to prominence in the ‘90s with his influential club hit, “Cunty,” catching the attention of everyone from Janet Jackson to Whitney Houston and Madonna. And more than 25 years after “Cunty” first hit dancefloors, Aviance has also now made himself known to Beyoncé, who’s ensured the track will live forever as a sample on her song, “Pure/Honey.”

Taken from her seventh studio album, Renaissance, “Pure/Honey” is just one of sixteen sonic love letters dedicated to “pioneers who originate culture,” specifically queer Black artists like her late “godmother,” Uncle Jonny, and all the other “fallen angels whose contributions have gone unrecognized for far too long.”

“It’s been overwhelming,” Aviance said of the public reaction to the use of his song, which he didn’t know he was featured on until a friend told him.

“I literally passed out. I hit the floor,” he recalled with a laugh, adding that he can’t help but “feel like a kid in a candy store,” because “it’s been a couple of weeks and I’m still sitting here looking at ‘Pure/Honey’ like, ‘girl.’”

Even though widespread recognition of New York’s drag and vogue-ballroom scenes has been a long time coming, Aviance found the years between the community’s heyday and his own “renaissance” difficult. As the laws surrounding New York nightlife became more and more stringent, the clubs closed and the scene got quieter. Then in 2006, Aviance was beaten and almost killed in an anti-gay hate crime in the East Vilage, which kept him away from the city for over a decade.

“It was hard. I was dealing with addiction and my mother, my best friend in the world, was gone,” he said, before explaining that he only came back to get his hips replaced a few years ago. But after quickly “realizing that I couldn’t leave again,” Aviance returned to a dramatically different version of queer New York nightlife, which had moved across the East River to Brooklyn in the time he’d been gone.

Even so, Aviance was “inspired” by all the younger people that he met, including members of the House of Aviance and other queer Black artists, as someone who’s “always believed in letting the new people through.”

“If someone is fiercer or incredible, I’m here for it,” he continued, before pushing back against the accusations of “stealing” surrounding Renaissance, specifically her so-called “appropriation” of vogue and ballroom culture on “Pure/Honey,” despite Aviance confirming that she “took care of business” in terms of clearing the sample.

“It doesn’t feel like stealing to me. It feels like somebody honoring. And at the end of the day, the album is still Beyoncé, even if it’s maybe a new sound for her or whatever. But you can also see in the vocals and all the stuff that it is her,” he said. “We’ve been injected inside her brain and her feelings, and she’s taking it in and using it, which is what art is all about.”

He added, “Art isn’t about not being influenced. It's about what you get influenced by.”

So when it comes to the alleged appropriation of drag and queer Black culture, Aviance said that Renissance is very different from something like Taylor Swift’s music video for “You Need to Calm Down” or Harry Styles’ “whole kumbaya wearing dresses” thing.

As he explained, Beyoncé’s project is all about “recognizing these Black icons that really don’t get much voice” through her powerful, globally recognized platform, meaning that Renaissance was a moment of rebirth for Aviance, as well. And according to him, the results have only been positive, both in terms of potential career opportunities and his past work, including tracks like his recent single with DJ Gomi, “I’m Back.”

“And for her to hold us up like this — this Black diva, this Black queen — there’s nothing better in the world,” as Aviance concluded, a hint of disbelief sneaking into his voice. “There’s really nothing better.”

Welcome to “No Last Name Puns,” a column by Sandra Song about all things music. Featuring everything from profiles on rising artists to explainers on emerging scenes to cultural analysis of both new and old musical releases from every genre, “No Puns About My Last Name” is all about exploring the relationship between music and culture through more than just premieres and "first looks."

Photos via Getty

From Your Site Articles

- COBRAH Premieres "GOOD PUSS" Off Forthcoming EP - PAPER ›

- Bushwig Announces Its 2022 Lineup - PAPER ›

- Beyonce Responds to Right Said Fred's "I'm Too Sexy" Sample Complaint ›

- Beyoncé Announces Renaissance World Tour ›

- Beyonce Fans Heckle Harry Styles Over Grammys Win ›

- Beyoncé Reportedly Had Unreleased Music, Tour Plans Stolen - PAPER Magazine ›

Related Articles Around the Web