In the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh lies Benaras, one of humanity's oldest cities set on the banks of the River Ganges, considered holy by those of the Hindu faith. The Eternal City, as we call it, is home to hundreds of "Akharas:" rural gymnasiums that train young Hindu men in the spiritual and martial traditions, readying them to live their lives according to long-established cultural and societal norms. Here, young boys and men work and study together. One part of their training is "kushti:" the art of hand-to-hand combat. And, like all hypermasculine sports, Kushti, too, attracts speculation, conjecture and the alternative gaze. Over time, Akharas and their activities have come to be chronicled through a largely sensual lens.

Images of oiled, muscular boys and men wrestling in the mud, bathing in the Ganges, or spending time with each other on the parapets of crumbling temples have been captured in popular visual narratives — travelogues, photo essays, and now, increasingly on social media — adding to this Orientalist fantasy.

But this biased chronicling ignores the dichotomy of the Akharas' very existence. For all their openness with the male body, the Akharas system (it exists in other small towns and cities as well) is the product of a deeply patriarchal, largely rural dynamic that prizes, above all, strength — physical, mental and spiritual. It has no female equivalent.

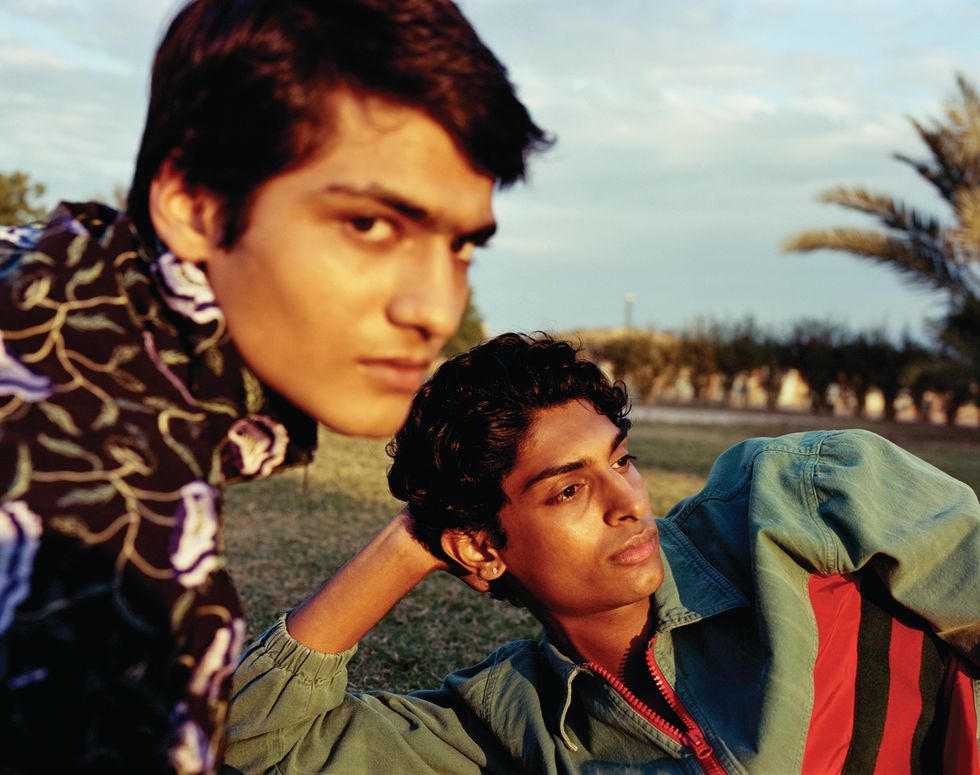

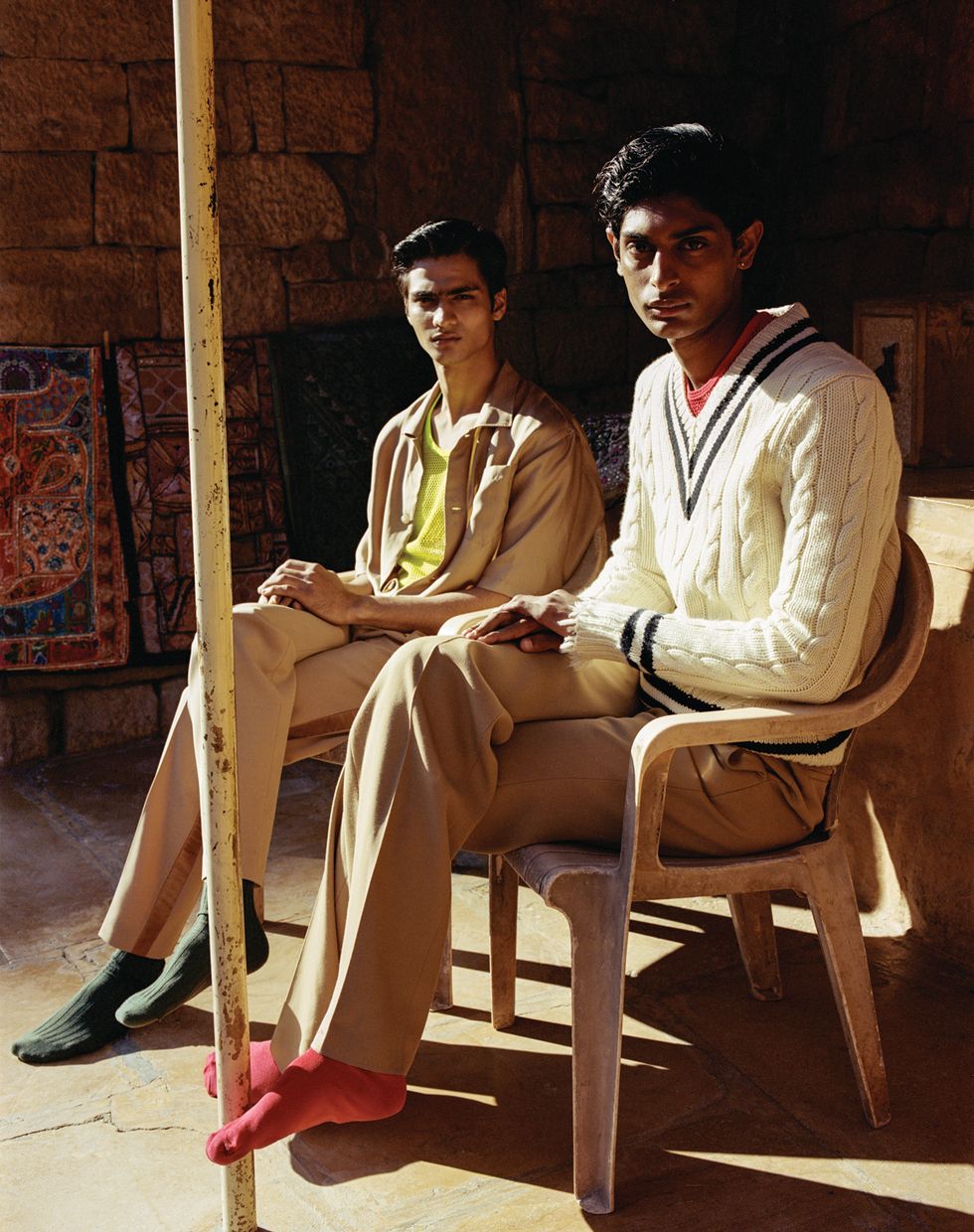

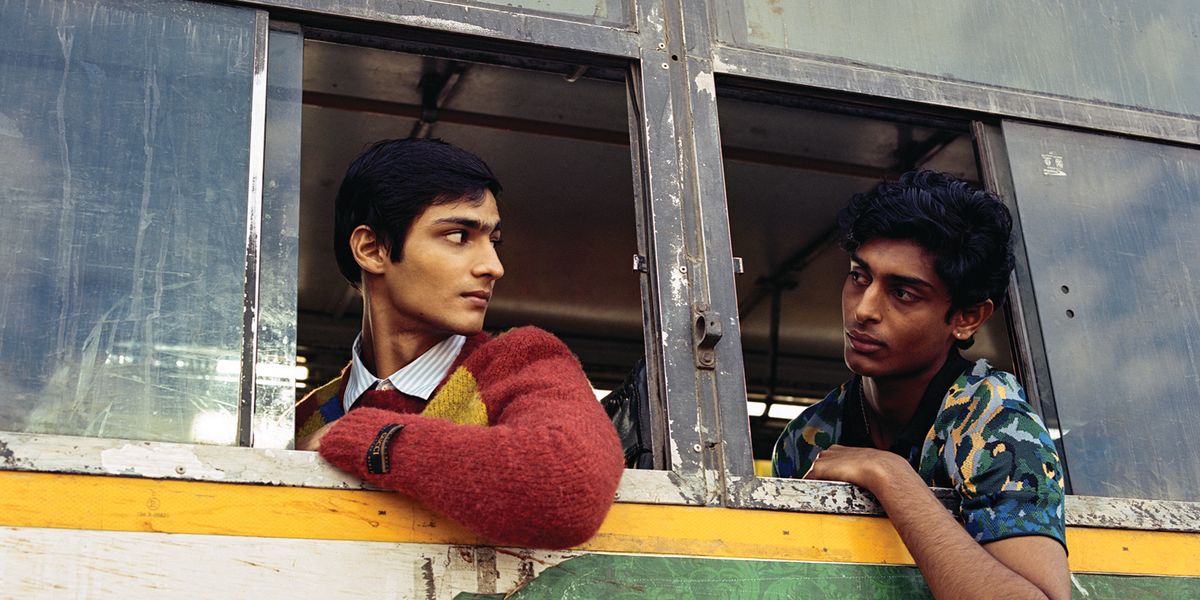

Outside of the Akharas, where the show of masculinity and homosocial interactions are ritualized, rural India's young men opt for more casual forms of self-expression amongst friends. The marketplace, another closely chronicled aspect of life in small town India, is their space. It is here that travelers, especially from the West, are surprised by the simple act of two men holding hands. They question it from a heteronormative viewpoint: "Why are men holding hands in public?" I re-phrase the question slightly: "How are men so comfortable holding hands in public?"

In a rural setting — where patriarchal mindsets are generally the norm — boys grow up without much female companionship other than their caregivers and immediate family — mothers, aunts, sisters and cousins. Friendship between genders is frowned upon (though not unknown), and male children grow up with a very real sense of responsibility towards the household and the family. It's no surprise, then, that outside of the homestead, they do everything in all-boy groups: exploring the countryside, raiding mango orchards in the summer, playing, bathing in lakes and streams and, yes, holding hands. And nobody gives them a second glance unless you're a tourist or a city person.

Absent any interaction with girls their own age, they express themselves with their male friends openly and easily, almost as if in compensation. There's a necessary softness to their social interactions, one that allows them to experience the comfort and reassurance of the human touch.

In a patriarchal society like that prevalent across large parts of India, this becomes important to growing boys. So important that as a theme, male friendship has been a staple for decades in India's most influential artistic medium accessible to the public: Bollywood films. Blockbuster hits like Sholay (1975, the highest grossing Indian film of all time, adjusting for inflation), Karan Arjun (1995) and Dostana (2008), amongst numerous others, all revolve around the idea of friendship between men.

Without going into the particulars of how these movies explore male bonding (which would take a whole other article), it is a significant genre that, even when not central to the storyline, portrays male friendship far beyond the expected trope of the best friend as a wing man. And Indian men, fed this combined diet of patriarchy and Bollywood, hold on to their buddies something fierce.

The fact is that small town India continues to "go" to the movies. While access to the internet has boomed in the last decade, it is cheap mobile phones that have allowed and yet restricted rural India's online experience to social media and gaming apps. Even as online streaming services become popular throughout India's prosperous cities, the movie theater remains the social hub of the country's smaller towns. Here, moviegoers get more than just fashion tips from their favorite actors. They also tend to adopt speech, behavior and social patterns from them. It was actor Salman Khan's flaunting of his perfectly chiseled body that led to a boom in gym culture in rural areas in the '90s.

With this particular audience in mind, an increasing number of Bollywood movies made in the last decade feature small town life, and the trend's still very much with us. Films like Bareily Ki Barfi (2017), a rom-com set in Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh about a headstrong girl who falls for a bungling romantic, or Kai Po Che (2013), a story of three friends from Ahmedabad in a time of communal discord — just to name two — capture rural India's vibe in a very "real" way. They even give city moviegoers a peek at a life they will never experience firsthand.

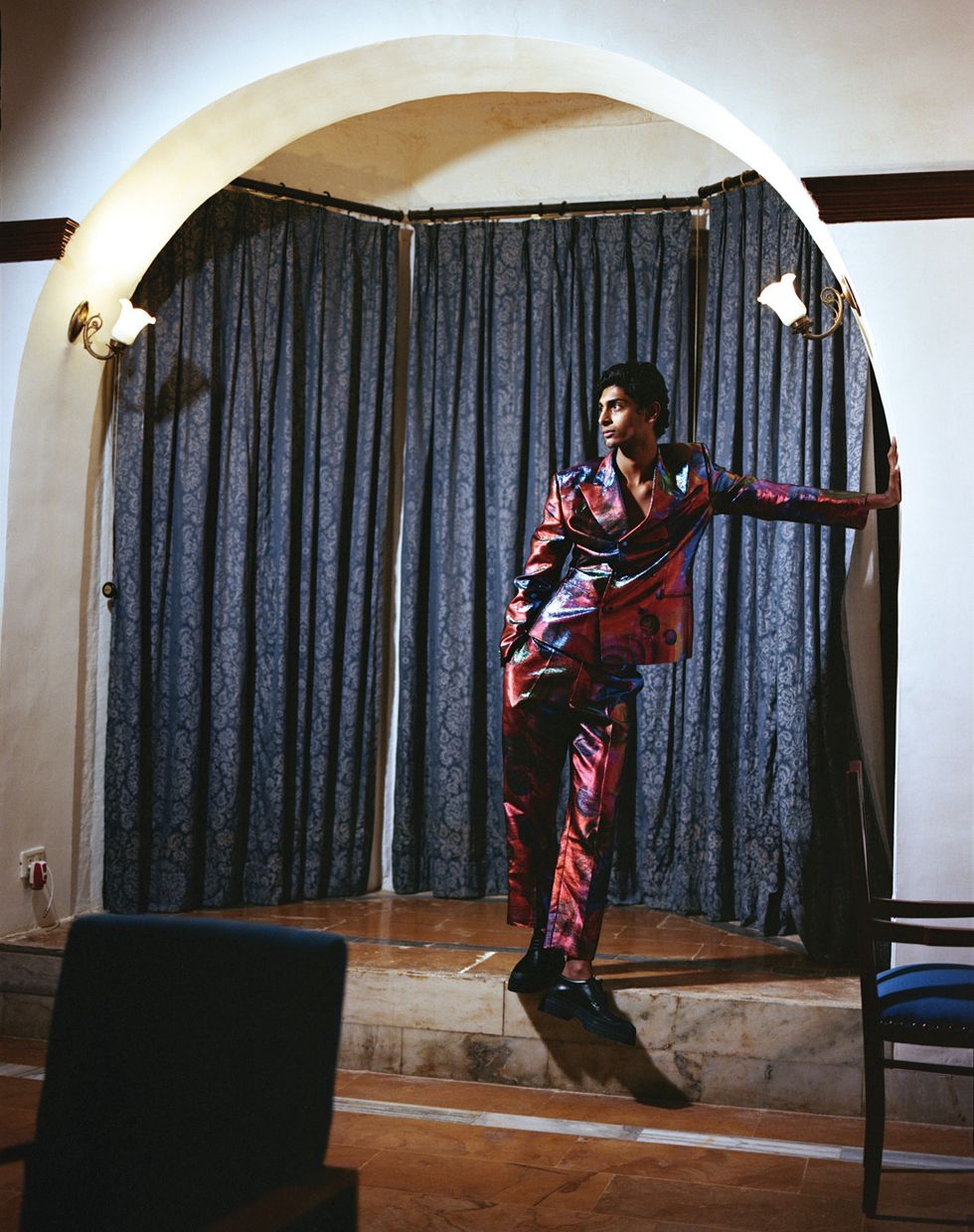

It is in storylines like these that complex ideas of male friendship, camaraderie and displays of emotion are explored by a new breed of male leads who have, through their work, broken the stereotype of the masculine Bollywood hero prevalent until the 1980s. Actors like Rajkummar Rao, Sushant Singh Rajput, Vicky Kaushal and Ayushmann Khurrana now champion a softer, more sensitive masculinity that's OK with discussing problems, crying and asking for help on-screen. And the young men of small town India are drinking it in.

This change didn't come about simply because Bollywood producers saw dollar signs flash across their eyes. It started in the late 1980s and early '90s with the opening up of the Indian economy and the fall of the Soviet Union. In a short while, we were given a crash course in Western pop culture. And it wasn't the latest shows that aired here. We watched The Wonder Years a few seasons late, ditto Santa Barbara and Small Wonder. We got hooked on The Bold and The Beautiful, and even got a Mexican telenovela from 1985 called No One But You (this one dubbed into Hindi).

What English-language TV series — dubbed or broadcast in the original — did for Indian audiences was to bring in new cultural suggestions and break existing mores. For example, the idea of running errands and taking up chores for pocket money hadn't existed in urban India until we saw it in Western series like Small Wonder. We also saw a wider range of male characters played by the likes of Fred Savage in The Wonder Years to Ronn Moss in The Bold and The Beautiful. Indian television at the time was booming, too, with path-breaking TV shows that brought home the struggles of the new India. We were ready for a different kind of male lead in our films. And soon, we were to get one.

It was in 1992 that Shah Rukh Khan (SRK) made his Bollywood debut. Having worked in television in acclaimed shows like Fauji (1989; a series based on the lives of Army cadets) and Circus (1989-'90; the story of traveling circus entertainers), he was to become India's first big crossover star. Nobody could have predicted it at the time, possibly because his choice of roles in some of his first big movies — especially Baazigar and Darr (both released in 1993) — was unusual, to say the least.

Just a year into his 1992 debut with the romance-action-drama hit Deewana (he played second lead and won Filmfare magazine's Best Male Debut award), he chose to play an obsessive lover in Darr (literally, "Fear"), chilling hearts with his stammering, psychotic delivery of the now-iconic dialogue: "I love you, k-k-k-Kiran!" He then went on to shock audiences with his role as a girlfriend-killing lover in Baazigar, a film that broke all the sacred tenets of Bollywood chauvinism. Audiences jaded by decades of cookie-cutter romances sat up and took notice. And SRK did this at a time when it was considered sheer stupidity for a rising lead actor to take on negative roles. In going against the grain, he set the template for future actors, and enabled them to portray a variety of characters without the fear of being stereotyped. Cracks had begun to appear in another Bollywood trope.

No less inspiring was his personal history. Known today as the King Khan of Bollywood, SRK hailed from a middle-class family in Delhi, and came to Bombay to get away from the spectre of his mother's death. He rose to become one of India's most celebrated actors because of something no male lead had dared expose on screen before: sheer vulnerability. After that, he came to represent a new style of Bollywood hero; his success led to the creation of an entire genre of scripts written for lookalike roles. And his films created the space for future actors to explore their characters' many and varied aspects in the movies that have followed since.

On the ground and away from movie screens, we are in a pivotal time right now. Rural India's young men are assailed by two very different ideologies. On one hand is the resurgent far right, who often employ a political propaganda machine (usually via Whatsapp) to send predictions of doom unless young men "man up" and protect their women and homes. On the other is the liberated world of Bollywood films that brings them visions of fulfilling friendships and displays of vulnerability. These mixed messages are confusing, and finding a way to navigate these crosscurrents can feel tricky.

As young men today fear going adrift amid a deluge of fake news as well as the uncertainty of a flailing economy, India's young men look for that strength in the steady grasp of a friend's hand.

Photography: Ashish Shah

Creative Direction and styling: Kshitij Kankaria

Makeup: Melissa Chang

Fashion Coordination: Ruhani Singh

Production: Imran Khatri Productions

Photography assistant: Abhishek Rao

Styling assistant: Rebecca Anderson

Talent: Pratik Shetty (at Anima Creatives), Farhan Alam (at Inega)

Locations: Jaisalme Fort, Suryagarh, Jawahar Niwas Palace, Rajkumari Ratnavati Girls School, Jaisalmer, India

From Your Site Articles

- Indian Guru Sadhguru On Living a Joyful Life - PAPER ›

- Shedding the Last Layer: Gay India Awakens to New Freedom ... ›

- Inside Bombay Ballroom: India's First of Its Kind Drag Show - PAPER ›

- Indian Guru Sadhguru On Living a Joyful Life ›

- Inside Bombay Ballroom: India's First of Its Kind Drag Show ›

- Shedding the Last Layer: Gay India Awakens to New Freedom ›