The Best of EXPO Chicago and Barely Fair 2024

By Harry Tafoya

Apr 29, 2024I grew up in Southern California, where every once in a while you’d hear news stories about private beaches that weren’t actually private. By locking up gates, putting up notices and even building illegal architecture, a handful of rich homeowners were able to create the impression that what had always belonged to everyone was the sole domain of a select few. The art world works along a similar principle. Its barriers to entry are half-visible; its signs bear mixed messages. My most cherished childhood memory is of running over a sand dune and into the ocean in an almost delirious state of happiness. I don’t remember the specifics, all I can conjure up is the warmth of the sun and the feeling of my heart rising out of my chest as I pummeled into the surf. I mention this because art, for me, is a matter of experience rather than ownership. Sure, there’s a sizable bulk of contemporary art dedicated to complicating what you see: reminding you at all times that there’s a bigger, infinitely more fraught picture than what’s directly in front of you. But it’s also really not hard to recognize the frame of commerce, count the million-dollar houses lining the boardwalk and still appreciate the crunch of sand beneath your feet for yourself.

I recently went to EXPO Chicago, the largest art fair in the Midwest, to survey the work and see how Lake Michigan passes for an ocean. The main attraction of any art fair is the build-up of potential energy: the piling-on of odd celebrity sightings, champagne receptions and all-night parties crammed into the space of a single weekend. Unlike galleries, whose sleight of hand is to draw your attention toward the work and far away from its price tag, art fairs are all business, often shamelessly so. Everywhere you look: deals are being struck, power suits are being donned and the sight of small red stickers means that somebody is in for an unbelievable payday. Even if it initially seems more impenetrable than fashion week, the threshold to entry is lower than you’d expect.

Chicago is not one of the world’s major art markets, but it is a developed, tight-knit community and EXPO is very well-regarded internationally. The recent 2024 edition was the first to be held under the new ownership of the Frieze, the massive art festival conglomerate. This seemed to be the source of some anxiety. In the 12 years since its launch, EXPO had developed a degree of personality to it, one most associated with its founder, Tony Karman, a handsome older man with the frenetic enthusiasm of a talk show host, who was unmistakable all weekend with his bald head and flamboyant pocket squares. The fear then was that the fair would professionalize out of its (relative) scrappiness: upping the taste level (and the price tags), but losing out on its sense of character. Some marketplaces genuinely do feel unruly and exciting and alive, but even at its most quirky, the elite art world is rivaled only by Washington, D.C. in its commitment to being straight-laced and lawful evil, the key difference being that art people actually bother to get their suits tailored. Even if EXPO was the tentpole attraction for the weekend, it was the in-between moments, on and off the calendar, where the city’s creative community most forcefully asserted its personality.

At an art fair, you quickly give up devoting museum-quality attention because there’s too much visual overload. Blindingly colorful canvases vie for your attention with ultra-polished, space-ship sleek sculpture and fleeting glimpses of genuine masterpieces. Occasionally, a gallery will go above and beyond what’s required, drawing stylish little connections between their artists that emphasize that curation is as central to their business as making money. More often, they will either showcase one standout artist or throw spaghetti at the wall with all of the best works they have to offer.

David Lusk Gallery from Tennessee fell firmly into the first category, with one of the all-around best curated booths. The loose concept that linked Greely Myatt’s gnarly hand-stitched sculptures of stars, John Selvast’s pop art assemblage of cheap romance novels and Maysey Craddock’s stitched-up paper bag paintings was brute craftsmanship: manipulating raw material into new forms until they appeared beat-up but oddly beautiful.

By contrast, there was virtually nothing shoddy about Gana Art’s presentation. The Seoul-based gallery showcased a number of artists who update traditional Asian art styles while remaining incredibly refined. Park Dae-sung’s monumental painting straddled the line between abstract expressionism and calligraphy, deploying a huge mass of severe jet black that made you think of Franz Kline if his work were elegant and not a gestural mess. Japanese artist Chiharu Shiota was the real star, though, using tangles of blood red thread to create abstract patterns like veins which snaked and eddied over a snow white canvas.

Michael Rosenfeld gallery in NYC and Cristea Roberts from London flexed hardest in terms of how many diverse big-ticket artists they could fit onto their wallspace. Rosenfeld specializes in mid-century Black art and provided banger after banger from gorgeous Alma Thomas and Beauford Delaney color fields, chintzy Claire Falkenstein sculptures, to what is now my favorite Robert Colescott painting: a landscape of giant undulating hot dogs. Roberts’ booth, by contrast, was an orgy of graphic color, pitched between Modernist masters (Anni and Josef Albers), spidery-to-flowery figuration (Paula Rego and Yinka Shonibare) and heaps and pools of pigment (Ian Davenport, Polly Apfelbaum and Idris Khan).

Local Chicago gallery Mickey and New York’s Fragment were my two favorite two-person shows. At the former, Ryan Nault’s Cézanne-like still lifes of fruits were simple, striking and lush, which made their presence beside Amy Stober’s sparkly, high-femme baggage all the more funny. There was plenty of really terrible glittery art at EXPO, which showed how eye-catching work can also be completely forgettable and boring. Stober, by contrast, did a lot with a little, highlighting her gift for recreating texture while also getting truly silly with it. At Fragment, Michelle Cho’s award-winning, ragged sculptures of tire parts were excellent, even if I didn’t totally buy the critique of consumer capital they were supposed to represent. The pairing with Meredith Sellers’ brilliant charcoal drawings of car crashes, however, was completely inspired, as if Cho’s debris had skidded out of Sellers’ worst nightmare. Very chic, very Crash.

Other standouts: Tyler Vlahovic’s swooning geometric abstraction at Chris Sharp, Rajni Perera’s surrealist-animist vision of Sri Lanka at Patel Brown; Ohad Meromi’s gloopy towering behemoths at 56 Henry; Andrew Norman Wilson’s turkey gizzard body horror slotted beside Jimmy DeSana’s slapstick ass cheeks at Document; every imaginable print by the late, great Faith Ringgold who had passed away only a few days prior to the fair at ACA Galleries; the survey of Australian Aboriginal artists at SmithDavidson gallery, but especially the gorgeous paintings by Emily Kam Kngwarray; Lilliana Porter’s witty assemblage at Secrist Beach; Donald Sultan’s deceptively dainty paintings at Ryan Lee; and finally an absolutely breath-taking Édouard Vuillard called “Under the Portico” (1899) at Thomas Gibson Fine Art that I spent an embarrassing amount of time just staring at, probably catching flies with my open mouth. Works that beautiful always leave me with a sense of tragedy that, unlike in a museum where they might be switched into rotation, it’s exciting to catch a glimpse of them and just as hard to say goodbye.

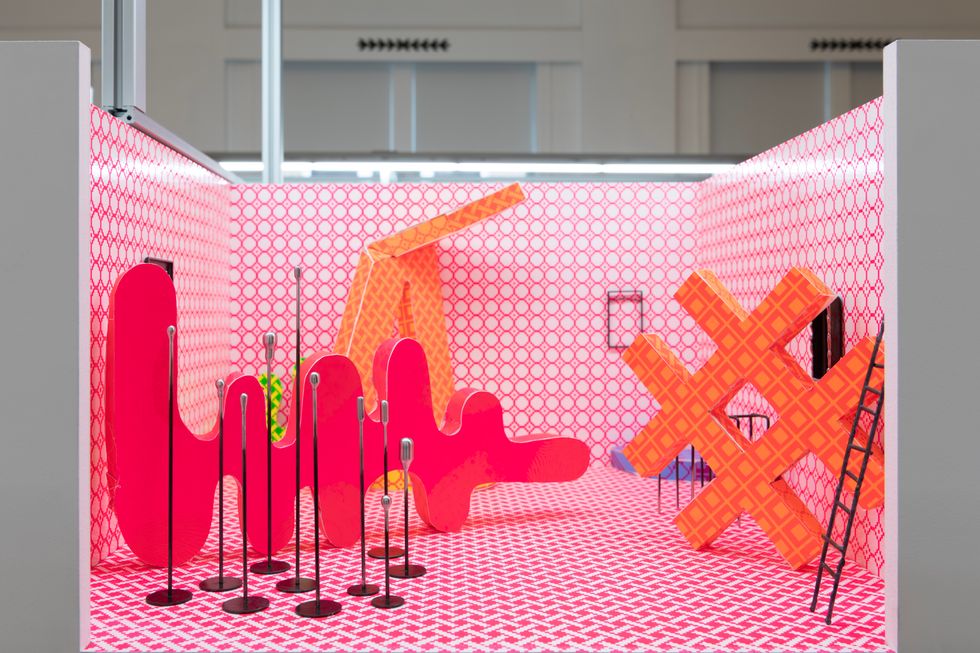

I left the fair in a kind of visual mania and needed to get some perspective, so the next day I went to Barely Fair. The exhibition is a scaled-down version of an art fair and featured a number of the galleries that took part in EXPO. The best “booths” occupied the space of a small dollhouse each and featured work built-to-scale. Carla Grunauer from Buenos Aires gallery, Piedras, made a suite of creatures inspired by the wildlife of Patagonia that had the same kind of angular whimsy as Jean Cocteau’s drawings. Irish artist Stephen Brandes’ sculpture of a charred miniature cow for Askeaton Contemporary Art worked on a similar wavelength, looking like it was pulled from Alexander Calder’s Circus, although the miniature scale doesn’t really service the diaspora story he wants to tell. Casey Jargo from Arizona gallery, Everybody painted shit-posts the size of postage stamps with some near microscopic details. Low-concept, high effort, very stupid funny. My personal favorite was Mark Fingerhut from Chicago's Sulk gallery, who hung a tiny minimal black square in the corner of the booth that was reminiscent of Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square” (1915). Unlike Malevich, who aspired to create a blank slate for human creativity to triumph over, Fingerhut’s work isn’t perfectly black. Look carefully and you’ll see two barely perceptible dots touching and circling one another in a miniature dance. “Pixel Piece (for Rebecca)” (2024) is a tiny bit of software for a bite-sized work of art, but it’s a very sweet gesture, a love letter that’s incredibly affecting despite its tiny size.

MORE ON PAPER

Entertainment

Dove Cameron and Avan Jogia Broke Their Molds

Photography by Gustavo Chams / Story by Joan Summers

Photography by Gustavo Chams / Story by Joan Summers

18 February

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October