Debut Novelist Brandon Taylor Reimagines the Campus Novel

by Greg Mania

Mar 06, 2020

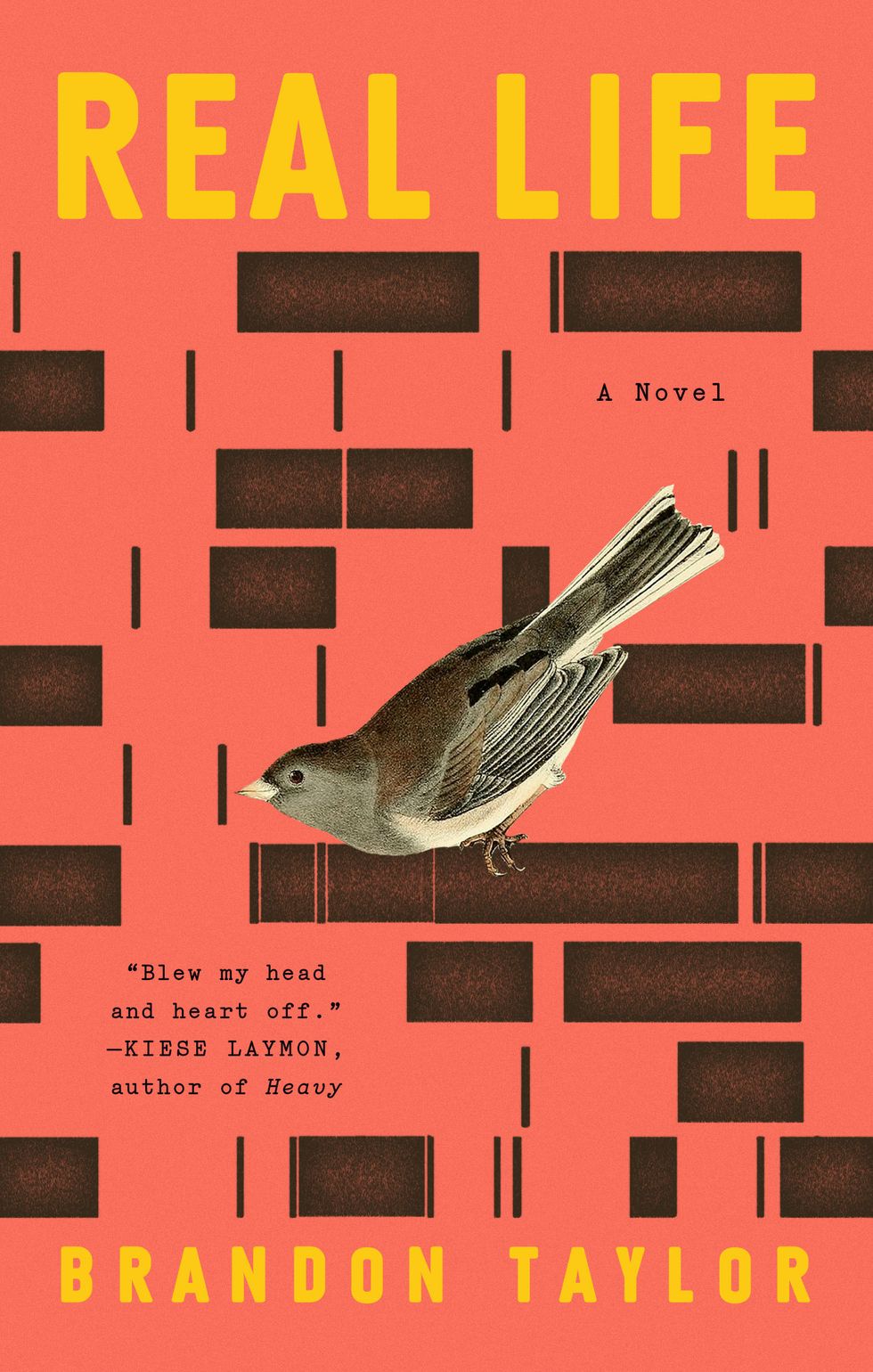

Birds do it. Bees do it. Even educated fleas do it. Let's all do it: let's all have a meltdown over how good Real Life by Brandon Taylor is. Book Twitter and every outlet alike has been singing its praise: from The New Yorker to O, The Oprah Magazine to The New York Times, the latter also running a profile to boot. Like Shen Yun, you can't escape it. And you don't want to.

Real Life follows Wallace, a young Black queer graduate student studying biochemistry at a midwest university, over the course of a single summer. He questions whether he should leave his program while his friendship with Miller, another graduate student and member of his close-knit friend group, escalates sexually and emotionally, forcing Wallace to contend with the horrific trauma of his past. But his growing doubt — whether he belongs, here, with his friend group, with whom he feels both love and alienation, his lab cohort, and the town in general — isn't just a result of the racial, class and sexual tensions he's navigating, but a general disconnect from within — a belief that we can never truly know each other at all.

A nesting doll of rich narratives, crucial themes and captivating characters, Taylor's writing is vibrant as much as it is brutal in its elegance and poignancy. The author invites us to consider friendship, intimacy and community, and asks us, What makes it real?

PAPER caught up with the 30-year-old author to talk about his revelation of a novel, his duality as a scientist and a writer, and how Real Life forces us to have the uncomfortable — but necessary — conversations we need to have, below.

How does your background in science influence how you approach writing a story?

I'm sort of wary of getting essentialist about this sort of thing. I know a lot of disorganized scientists and a lot of organized writers, but for me personally, my science training is how I learned to organize and execute a large project like a story or a novel. I make notes. I get very regimented about my process in terms of how much to write and how often. I try to make it as unromantic as possible. I know that ruins the fun for some people, but for me, it's totally unnecessary to get anything done. I need a plan.

Do you feel like your duality as a scientist and a writer has helped you hone your voice in a way traditional writing programs can't? If so, how?

I'm not entirely sure that traditional writing programs can in fact help hone your voice. I left my doctoral program to attend a creative writing program, and honing my voice was not really a thing I experienced in terms of the actual classroom. I think that you find the way you want to write by writing and by spending time thinking about the material that feels most urgent to you. It's just that creative writing programs often provide structure and time for you to do that kind of thinking and writing. But it's nothing that feels inherent to the program itself. I found my voice because I wrote for myself. And I followed my interests. That's how you find yourself, I think, by writing and paying attention to what excites you.

Your sentences are crisp, oscillating effortlessly between delicate and brutal. There's humor and heart from beginning to end. How long did it take for you to find your style?

I recently looked back at some old writing I did, and I've been pretty much writing the same way for most of my life. I didn't go in search of a voice. I didn't go looking for a style. I just wrote. I think I must have been imitating writers I really loved like André Aciman and Joan Didion and Louise Glück, writers of tremendous elegance and emotional potency. The attributes I most admire in writing are clarity and precision, so when I write, I'm always trying to recapture the feeling I get from the writers I love. I want it to feel natural and easy. I try not to worry over things too much.

What books did you keep nearby while writing Real Life?

I read Persuasion, Sense and Sensibility, and Emma Straub's Modern Loversover and over and over while writing Real Life.

You have an affinity for the college campus narrative — we both have a soft spot for The Idiot by Elif Batuman — and now you've made your mark in that space. What made you want to write your own and what kind of mark do you want to leave?

When I decided to get serious about writing a novel, I knew that I had to pick a genre that I knew extremely well. The genre I know best is the campus novel. I also have spent most of my life, 26 out of my 30 years, in schools and on various campuses. I came of age, in some sense, on campuses. It just made sense that I would choose to set my first novel there. I also wanted to write a campus novel from the perspective of a queer Black person, because that wasn't something I had read before, and it felt really urgent to me at the time to write the kind of story that I wanted most to see.

Love and alienation co-exist for Wallace when it comes to his friend group. His identity markers — queer, Black, difference in class growing up — forge a disconnect for him among his cohort, school, and town in general. If this book were to continue, do you think Wallace would be able reconcile his feelings of love and alienation towards his friend group?

The short answer is no. It's interesting to me that people think that Wallace would be at ease among a group of people who more closely resemble him in terms of race and sexuality and class. Wallace's alienation isn't just a result of the systemic factors he's trying to navigate. Wallace is a person who struggles to feel connection at all. He doesn't know how people are supposed to be with one another. It runs all the way back to his childhood. He just never learned how to operate. He always feels like he's guessing. So from Wallace's end, no, he would never be able to resolve love and alienation because Wallace doesn't think people can ever know each other.

But also, the fact is that Wallace isn't the only one who needs to resolve a tension. His friends also would need to be able to bridge the gaps in their own understanding of him. They would need to be able to step out of themselves and into the empathy gap, and I'm not sure they're in a place to do that. So much of the novel dramatizes what it's like when people who are unable to connect for a variety of reasons, from all sides, stumble toward each other without realizing they haven't actually connected.

It comes across, to me at least, that Wallace's friends, well meaning as they may be, are the type of people who would say they "don't see color," when Wallace's Blackness is the unacknowledged bedrock of a number of conversations they have when talking to/about Wallace. Why did you choose to write his friends in this specific way?

It wasn't a choice, I don't think. To write about these characters in a truthful way necessitated rendering the kinds of ignorance and mishaps and social gaffes that are common to progressive and liberal spaces in the United States, especially on college campuses. It's a fantasy that we live in an era where white people have a full and robust understanding of race and the ways that they themselves are complicit in oppressive structures even when they mean well. It would have been not only inaccurate, but morally bankrupt to write these characters any other way.

Like identity, you write about how trauma also embeds itself into the fiber of one's existence, both physically and emotionally. What do you want the reader to take away from trauma as it relates to identity, specifically?

I don't know if I have any trauma-specific takeaways because trauma is different for every person. Even in the context of Real Life, Wallace's trauma and Miller's trauma are different, and the ways that disclosing that trauma alters their relationship aren't the same. I think that sometimes we get into a situation where we're comparing our trauma to other people's trauma as a way to build connection or establish hierarchies, and that to me seems like a not entirely helpful way of operating in the world. I think the novel is my attempt at honestly portraying the messiness of trying to disclose something about yourself that feels fundamental but which is almost impossible to articulate.

Waller and Miller have respective relationships to violence, which manifest between them, especially sexually. Does pain from the past play a role in their mutual attraction?

I certainly think that Wallace is the kind of person for whom attraction is a difficult, complicated business. He has a fraught relationship to his body and to sex. None of it comes easily to him. And I think for Wallace, sex is always bound up with control and pain. It's always a matter of exerting power. For him, there is something really attractive and really potent about someone who has the capacity to destroy him. And because of his own past and his own psychology, that destruction seems really appealing. And I think Miller feels like he has to watch himself because he's aware of his own capacity to destroy and break, and he wants to be a different person. But there's something reflexively violent in him that he's afraid of, but also that comes out when Wallace goads him. It's a dangerous dynamic.

You make your love of the short story abundantly clear. Any plans to release your own collection anytime soon?

Yes! My publisher bought a short story collection along with Real Life. It's called Filthy Animals, and it'll be here in a while.

Real Life is available for purchase here.

Photo courtesy of Bill Adams

MORE ON PAPER

ICONOS: Pepe Aguilar, El Oficio del Tiempo, la Voz del Silencio y el Peso del Legado

Español

Jan 19, 2026

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October

Entertainment

Matthew McConaughey Found His Rhythm

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Greg Swales / Styling by Angelina Cantu / Grooming by Kara Yoshimoto Bua

30 September