Deception Lies at the Heart of This Queer Author's Debut

by Greg Mania

Feb 26, 2020

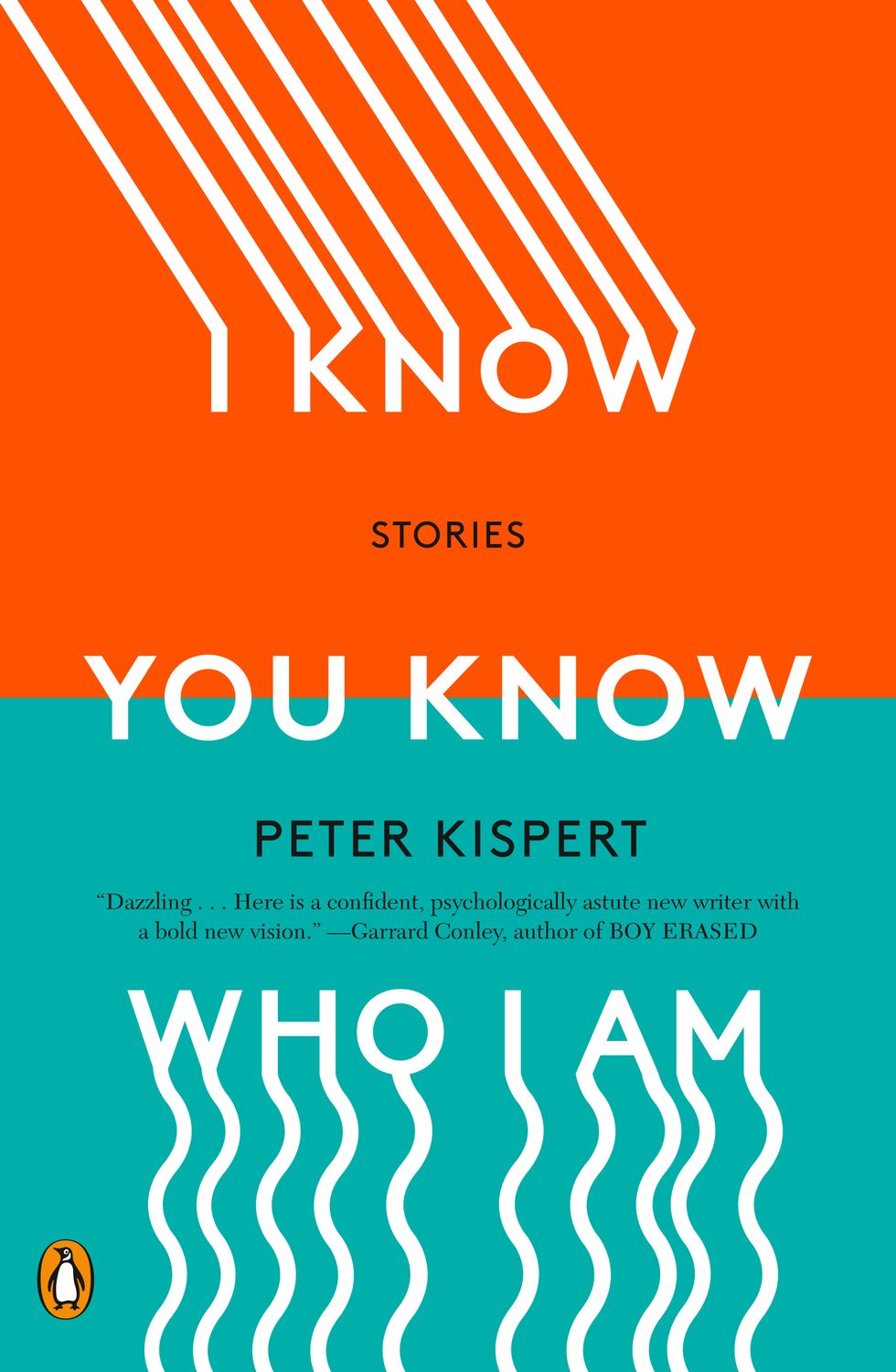

Peter Kispert's debut collection of stories haunt me more than the cumulative amount of times I've waved to a person who was waving to someone behind me. Each story in I Know You Know Who I Am contains a falsehood — from minor lies that roll off the tongue to elaborate deceits like hiring a stranger to play a fictional friend — that test the limits of how far we are willing to go to conjure the person we wish we were or could be.

But Kispert, an editor and writer, takes the already-nuanced motif, and puts it through a prism of queerness by examining how fraudulence can define or shape the queer experience. Each story mainly focuses on a queer character: there's a man who compulsively lies to his boyfriend about a faux friend, another who lies about his faith in order to court a religious man, and a man who risks his husband and daughter's life for the chance of a better life in a strangely ominous twist.

Kispert runs the gamut, oscillating between dystopic horror and giving the reader André Aciman-levels of feels, yet each story is connected — a powerful two-in-one tool that is transparent as much as it is reflective.

PAPER caught up with author-on-the-rise to talk about his buzzed-about debut, the correlation between queerness and deceit, and how deception can ultimately lead us to the truth.

Deception, lies, and mistrust are the narrative thread throughout your collection of stories. What made you hone in on this theme?

Each story is in service of a larger theme of self-betrayal. I'd been having a lot of trouble myself, after coming out, which I recall even now anticipating in my teens as a moment of almost salvation, because that's the prevailing narrative and sentiment around it — that or its opposite. Coming out too is often conflated with a kind of pronouncement of self-love, and there was a huge discord for me there. For about seven years I felt very fraudulent because I was not at home with myself; I wanted so badly to be a different kind of gay man — masculine, muscular, deep-voiced — and that feeling of inadequacy began to dictate so much. A tolerance to be seen as gay and a self-acceptance and self-love of that gayness — these things lived at first for me as I suspect they do and have for many queer people on different poles.

So while in the MFA, frustrated with trying to articulate someone else's idea of what a story is, or trying to hit all the marks of conflict or stakes or whatever I felt I was told I was supposed to do (yikes, all that remove), I decided to try to articulate what I was feeling. Because it was very complex, very conflicted. Really. It was a huge risk, and I felt it, to trust myself enough to write this book. It resulted in a work that coiled around self-betrayal — deception, self- and other — and well, honestly? That just felt and still feels so right.

Some of these falsehoods are minor, seemingly harmless, like lying about a skill you don't have, and some are elaborate: one of your characters hires an actor to portray a friend he invented. How does the magnitude of a lie inform who your characters actually are?

I've never thought very overtly or comparatively about magnitude per se, because all self-betrayal is of inherently a kind of maximum magnitude. The price is the self. But I did think about how to corner these characters, these people with their lies (often very ironically), so that they externally receive fleeting satisfaction and, also, the resulting unbearable inner turmoil of that reward. That makes these stories, to me, quite moral, almost fable-like in their articulation of the truth that we do not ever fully succeed in the embodiment of channeling desire through persona, our attempts at puffing ourselves up with knowing falsehood. At best, we are wasting time.

Your collection also mainly focuses on queer characters. How does the identity marker of queerness find its thread intertwined with those of deceit?

Queer people face so many challenges and the world is just not fair to them, to us. In a way, the roles to play to be accepted as a gay man, for example, are quite clear. And we can be rewarded for good performances. It takes a lot to reject those flattened roles and build out from a place of clarity and strength, in community. That doesn't mandate doing the opposite of these roles or place weighty value judgments on any characteristics. It just means trusting yourself enough to explore, to feel safe in being seen. Not by everyone, not all the time, not recklessly. But when it matters. What are you putting on, and what are you taking off? There's no judgment in that question. There's just the question, for each of us.

How does your book reflect the queer experience?

I want for it to! I really hope that it does. Readers decide.

I would consider a persona a hallmark of the queer experience — from trying to pass as something you're not to finding ways to achieve visibility. How do you see persona in this context?

I think it's really common and not inherently a bad thing at all. I think there's this contradiction you rightly note here — the nearly total freedom of persona. There is real freedom there, and I love that too; I do! In fact, persona can be helpful in finding who we are, what we value. I'm thinking here of how drag specifically can function to this end. But who's the audience for the persona, and why?

Your collection is divided into three parts, "I Know," "You Know," and "Who I Am." What is the significance of organizing your collection this way? Was it organized this way from the beginning and were any stories moved around until eventually finding their order in the book?

This organizational conceit came quite late in the process, as you might expect, and after realizing the bendability of the title. From one way, certainty — "you know who I am." From another, suspicion, wariness: "I know you know." Emotionally, I was also trying to lead the reader into the presiding consciousness over the book, and this device felt like a way of making that reading available, if not explicit. Within each section, I considered story placement by order as a kind of healing from compulsion, which so often looks at first like healing as we typically like to think of it — as gradual but eventual and maybe idealistically even inevitable — but which ends with an explosion, and then subsequent reentry into the cycle. That's quite painful to me, maybe one of the darkest elements of the book.

"How to Live Your Best Life" and "Rorschach" are profoundly unsettling, and I mean that as a compliment. What made you drift into the dystopian setting?

The "price of self-betrayal as the self" I mentioned takes an almost literal form in these two dystopian, more specifically public-execution stories. That was the intention. Thematically they feel as home among these more domestic or realist pieces for this reason. There's also just a lot of juice in these sorts of premises for me, a lot of opportunity for creation and world-building in an environment that seems just one step left (half a step, an inch some days) of our current reality.

Have you always had a proclivity towards the short story? Any plans for a novel in the not-too-distant future?

Short form has always interested me as a study in compression. It's let me develop my own skill as a writer and led me to the narratives and people that interest me most, that I feel most excited by. There's a novel in the works!

I Know You Know Who I Am is available for purchase here.

Photography: Brick Kyle (Courtesy of Peter Kispert)

MORE ON PAPER

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October