Genre Is Dead, Long Live Berhana

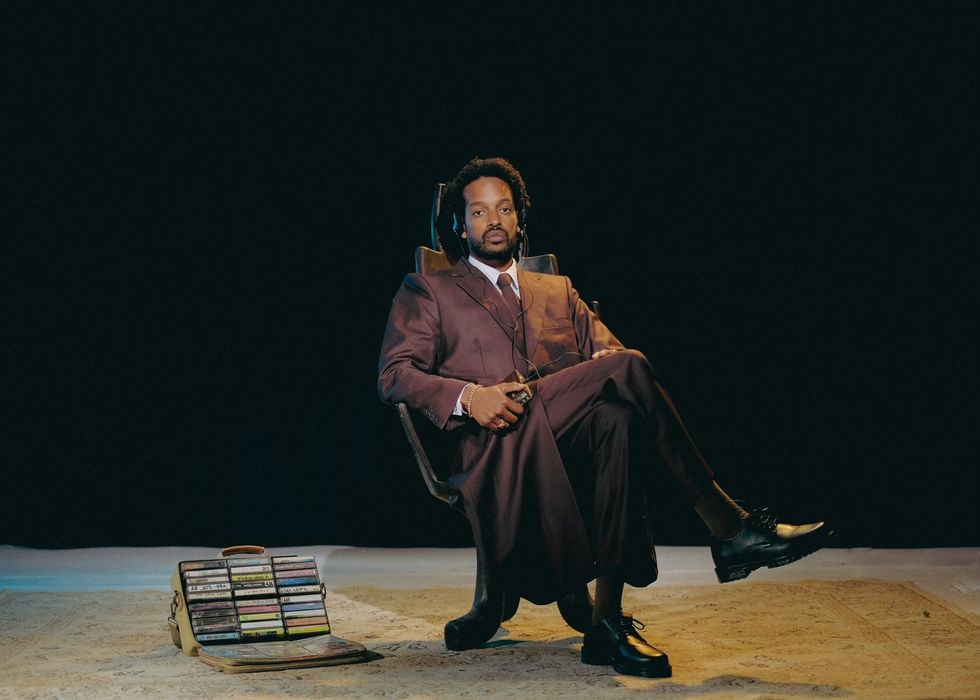

Story by Samuel Getachew / Photography by Girma BertaNov 06, 2023

Born Amain Berhane in Atlanta, Georgia to an Ethiopian immigrant family, the title of Berhana’s long-awaited sophomore album Amén የዘላን ህልም (The Nomad’s Dream) is itself a double entendre.

Amén, the Ethiopian pronunciation of “amen,” is also the pronunciation of Berhana’s given name. The title track and intro to the album depict a classic scene of home, overlaid by the sound of his mother knocking on the door and imploring in Amharic, “Amain! Amain! I’m calling you!” Released on Friday, October 20, Amén (The Nomad’s Dream) is an answer to that call — the call of spirituality, of family, of adulthood, of responsibility and of creative maturation. Taking cues from 2019’s debut album HAN, the progression of tracks on Amén defies continuity of genre in favor of a continuity of theme and storytelling. Berhana runs from the ego of his youth, faces it, grieves its death and accepts its lessons: “Found myself, then found my meaning,” he exalts on the track “Wow!”; the final track, “Going Home,” closes out the album with a voicemail from Berhana’s late grandmother, wishing the nomad safe travels.

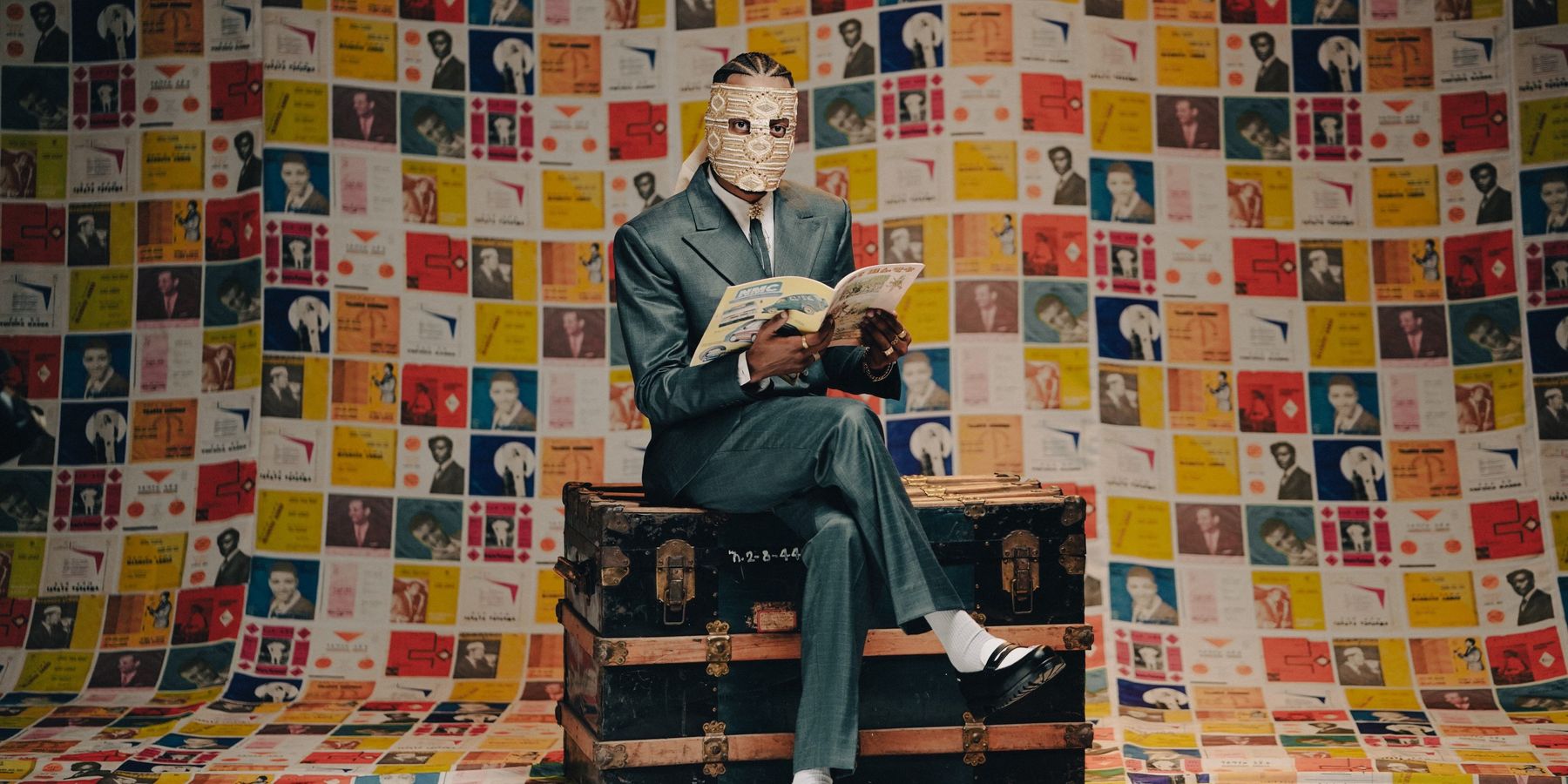

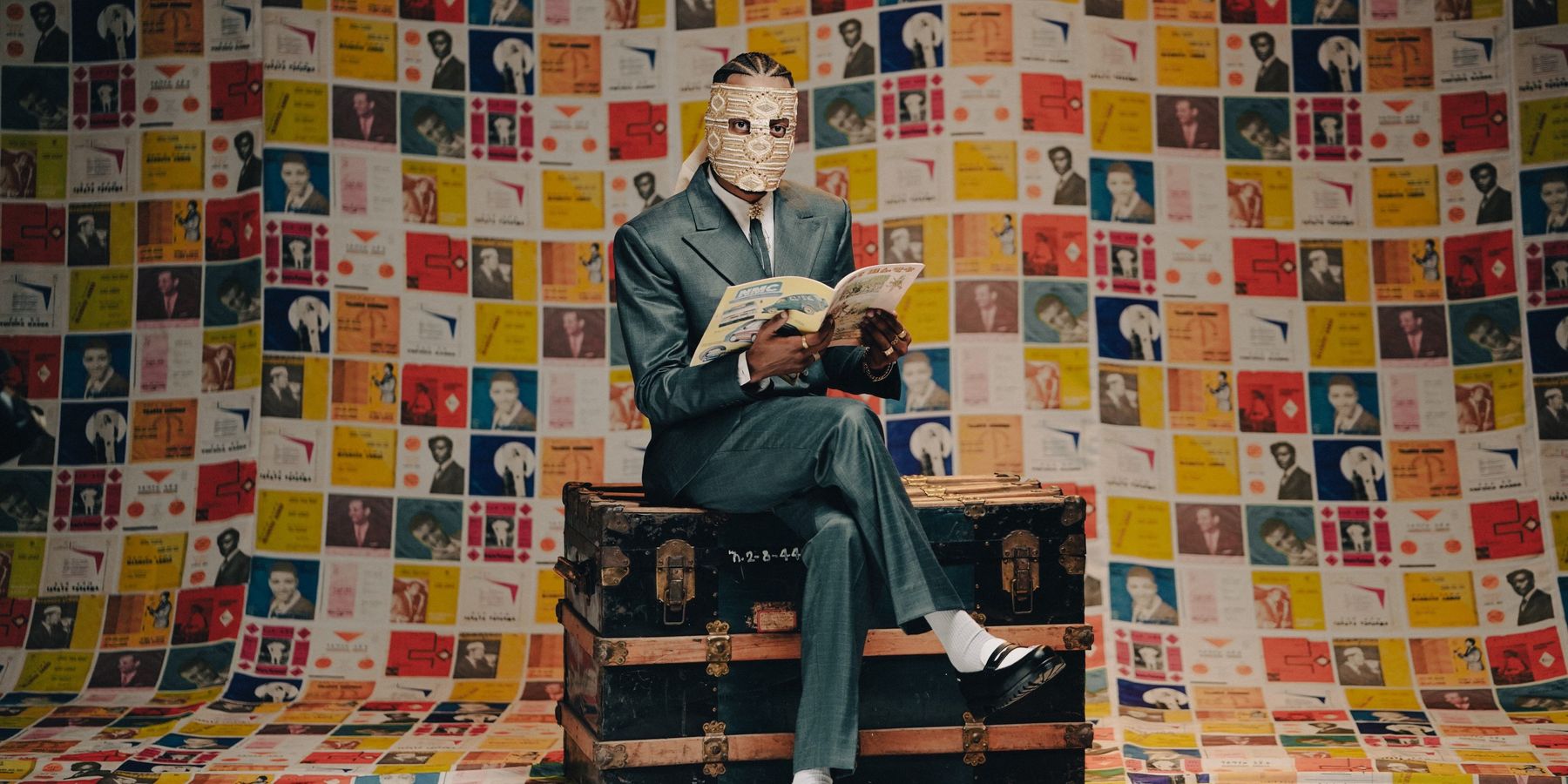

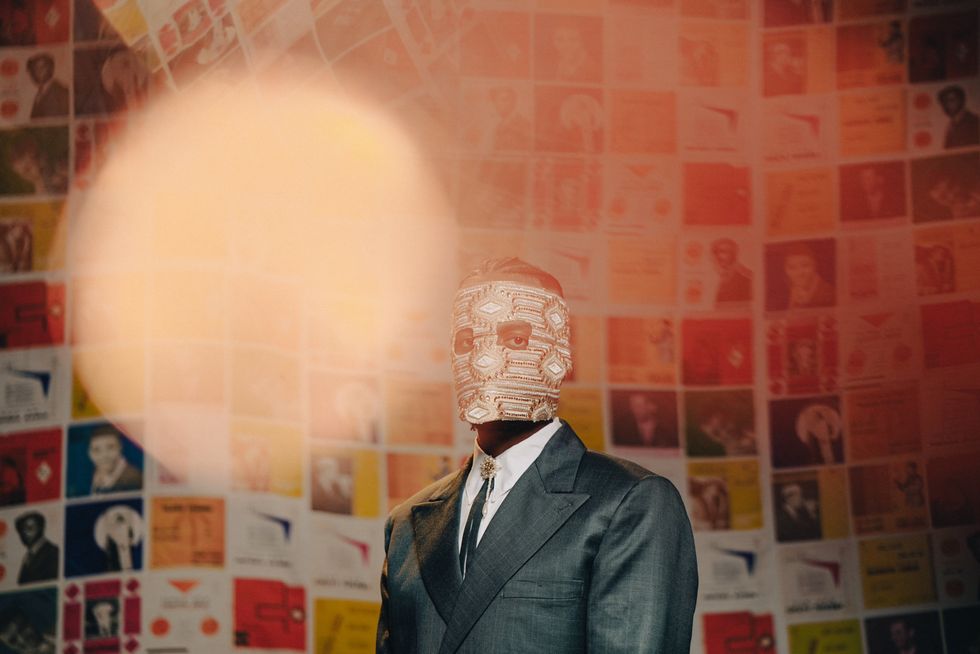

Berhana calls the accompanying short film his most “ambitious” project yet. Directed by Berhana’s longtime collaborators Julia Baylis and Sam Guest, the film reasserts the multidisciplinary artist’s storytelling roots in film and television with his newfound wisdom, deepened vulnerability and creative confidence. A visually lush celebration of Ethiopian culture and beauty, the film tracks Berhana through scenes of merriment and solemnity alike, featuring a captivating ensemble cast of Ethiopian actors and models. After its September premiere at The Roxy Cinema in New York City, Berhana held screenings of The Nomad’s Dream at theaters in Washington, DC, Los Angeles and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia leading up to the album’s release.

A few days before the release of Amén (The Nomad's Dream) and his final screening in Los Angeles, PAPER spoke to Berhana about life destinations, the obsoletion of genre and the trip to Ethiopia that catalyzed his sophomore album.

I want to start at the beginning – what was your relationship with music when you were growing up? Did you always see this as a path for yourself?

Music was something that was always around and something that I always wanted to explore. My brother and sister were both in musical theater. My brother was a dancer. He always had all types of music playing all the time. When I was really young I started making songs for myself, and then I started playing piano.

At first it was like nothing. It was something that was always just for me — it felt like a nice release. I was always in the mindset of, This will just be something I show my friends. I would do little shows here and there. Then I moved to New York to go to college for film and television. [The New School] had a great jazz program, and I became really good friends with a lot of the jazz kids. Through those relationships, I started jamming, making more music.

One guy in particular, he was like, “Oh, I'm making an EP, I heard you sing, you should get on it!” We did that together, and it ended up being received really well. After that, I decided to try and make my own song with my own name on it and see what happened. From that point on, it took off in a way I didn't expect it to.

I know you went on to work in screenwriting after college — where is it now for you as a priority, and what is the relationship between your screenwriting and your music?

I don't really think I see one as a priority over the other. During the pandemic, I was lucky enough to write on a few shows and continue to work within that space of television. When it comes to this album, I was able to help create this short film, which felt like an extension of all of that. As I continue to progress and grow as an artist, I think that muscle will continue to be utilized. Whether it's in this place of both music and film coming together or if I'm just focusing on one or the other, I still have a really close relationship to both.

I was reading an old interview that you did about your song “Wildin,'” and you were talking about the experience of entering the music industry, getting a taste of success then seeing all the destructive things that can come with that path. The hook of the song, “I'm hoping I don't waste this,” really stuck with me.

Now that you’re a bit older and more experienced, do you still feel that anxiety, of “I hope I don’t waste this?” If you could talk to the younger Berhana, what would you tell him?

I think I feel more secure in it now, but I'll still have days where those feelings kind of re-emerge, where it feels like I'm so lucky to have been given this opportunity and I don't wanna waste it.

I think if I were to talk to my younger self, I would say to have a little more trust in the process and who you are and what you're doing, because it's really good. I would say to continue to focus on the things that you believe to be meaningful and continue to harness that, and you'll be fine. You'll be protected within that. That fear, of, I'm gonna lose all my money right now or I'm gonna lose this opportunity to do something really great — that fear can be so materialistic in a sense. So, I think I’d just tell myself to relax and keep going.

I love that. I noticed in some of your earlier music videos, you're in motion, in your way somewhere. In the video for “G2g,” you're running, and in “Janet,” you're biking, and in both of them, we have these long shots that follow you down a solitary road.

This is a bit of a meta-question – in those videos, where are you going?

Damn. I think in all of those videos, I was searching for something. I wasn’t there yet, and in those moments, I wasn’t quite sure what it was. I was searching for some semblance of meaning and purpose and something that felt like where I was supposed to be or who I was supposed to be with.

Along with being in motion, all of these videos are focusing on someone by themselves. Loneliness is also a part of all of those videos too. I was trying to find my place, wherever that may be.

I noticed there are a lot more ensemble scenes in the film than in your earlier videos, and it’s beautiful to see that evolution, too. Speaking of the film and the new album, how are you feeling approaching this release versus the last one?

It did feel easier to make this album compared to the last one. There was a little bit of fear last time: This is really different, this isn’t like the last thing I made, I've never done this before, how are people gonna take it? I still wanted this thing to do well.

With this album — maybe because I knew what happened with the last album — I knew I was fine making something exactly how I wanted to make it. Also, I felt like I was trying to come into contact with something that felt really, really, really important to me. I was trying to discover things about myself. By making the album, I felt like I did something so good for my own soul. I felt like I gave myself a gift by doing all of that work. I think that also helped me realize that it doesn't matter whatever comes of this because I already got something I couldn't even have asked for.

Speaking of experimentation, you’ve long been critical of the boundaries of genre, and I’m curious, what are your feelings about it now? Have they changed?

Genre feels pretty dead to me at this point, even more so than when I spoke about it last time. Especially when you look at this newer generation, how they make music – you listen to one album all the way through, and it feels like you're listening to four or five different genres because the artists don't care about genre. Nor should they! Those walls are starting to come down in terms of how you want to express yourself and relate to the world around you to your experiences. I don't think you need to necessarily have the exact same sound in order to do that.

Absolutely. I remember at some point during the talk-back after the first screening of The Nomad’s Dream, you called the film ambitious. Why did it feel ambitious, and what gave you the courage to do it anyway?

It felt ambitious because before I had only made one video for one song at a time. This film was six songs, and I wanted it to have a narrative that you could follow throughout all six videos. I wanted to put all of the money I had behind it, which isn't an easy sell when you're talking with a label. Then you have to live up to that – we got the money, now let's deliver. It was ambitious but I really wanted to do it because I wanted to provide this additional layer to the album itself. I feel like it's easy to listen to the album passively and a lot of the ideas that I'm trying to put forth maybe don't stick as well. I wanted to create another entry point for people to interact with this album and this world. I'm really thankful we were able to do that.

I had the confidence because this felt important. What I was talking about as it relates to both my own upbringing and identity felt important, but also just what I was saying about life in a broader sense and accepting everything that it puts forth.

I also had so much confidence in the directors, Sam Guest and Julia Baylis, because we worked on almost every video I've done together. These are people I went to school with, that I'm really close with, that I'm lucky enough to call friends. It felt like this was our next step. I think this was our fifth video we've done together. I believe in these people so much, and they believe in me and it felt like we could do it.

How did you three meet and start working together?

I met Sam in a screenwriting class, on what I think might have been my first day of school. I thought he was a great writer, but also I saw some of the things he shot and I thought he was super talented. I met Julia through Sam. Then when I was making that first song, “Janet,” I sent Sam an email. I was like, “Yo, this sounds crazy, but I make music too. Would you want to do the video?” They were both so excited. That was the beginning!

In your past work, there have certainly been influences from your upbringing and culture, but I think this project takes it the furthest, from the title to the Amharic text to the visual. What made you want to lean in more heavily?

At the end of 2019, I went to Ethiopia for the first time, because someone had asked me to do a show out there, which I was really excited to do. I always wanted to go out there, and I was able to bring my mom with me as well. It was her first time back in 47 years at that point.

She had left thinking she was only going to be gone for four years for college. But then when war broke out, she had to take care of all of her siblings, make sure they could get out of the country. It was a really crazy time and for a lot of different reasons, she never wanted to go back, because she had this perfect image of what the country was in her head and she didn't want that to ever change. But luckily we were able to go back together and it was a really emotional trip. I got to meet so many family members I'd never met before. That was such a huge experience for me. That trip definitely served as the catalyst.

But then, a few months after that, one of my family members passed away. I had never lost anyone, and it really shook me. It made me want to learn about our family. I wanted to learn the language, I wanted to learn to read it, get closer to our world in every way. It lit this fire.

From that, it was a natural progression of the album, to the film, to even the character of the nomad, who is a traveler that’s able to bring home with him wherever he goes. That was something that was instilled in me, that I’m always trying to do, to bring that sense of home and family with me wherever I am because I’m far away.

That’s beautiful. At your screenings, you showed this short film made by Ethiopian international students at UCLA in the 1960s, called Have a Coke, before The Nomad’s Dream. Could you tell me about how you found that film?

I love that film. My friend Hannah sent it to me one day in 2019 or 2020 really randomly, just saying, “I think you'd like this,” and I became obsessed with it. I played it so many times. I thought it was so tasteful and so funny. I loved the framing and just being able to see these characters that reminded me of family, reminded me of my uncles.

Funny enough, when I was showing the film in Addis Ababa, somebody came up to me and was like, “Hey, this is so crazy, that was my uncle.” I was like, “I know what you mean, man.” They were like, “No, that’s actually my uncle,” and showed me a photo of the uncle on the phone, and it was the same dude in the film. I lost it. So crazy.

It’s such a small world! I love that you didn't just drop the film as a digital release, because there’s something so special about watching people communally experience it. How did you decide to have the screenings, and how does it feel to see people react in real-time?

We've worked so hard on it, I wanted to see it on a big screen. I wanted to talk about it. So it wasn't anything more than that. I just thought that would be cool. I think after having done three screenings, I've gotten so much more out of it than I could have ever hoped. The questions I’ve been asked from the audience to the conversations I've had with some of the moderators – I felt like certain things about the album and the film were being revealed to me in those moments, which is something I didn't expect. I thought I had all the answers. Hearing people's takes on things and the audience bringing up little moments that even I missed, I think that's been so beautiful and enlightening.

Absolutely. Once you make something and you put it out in the world, it doesn't fully belong to just you anymore.

Totally. I was talking about that the other day. It feels like you're just letting a kid go off to school and be whoever they're gonna be.