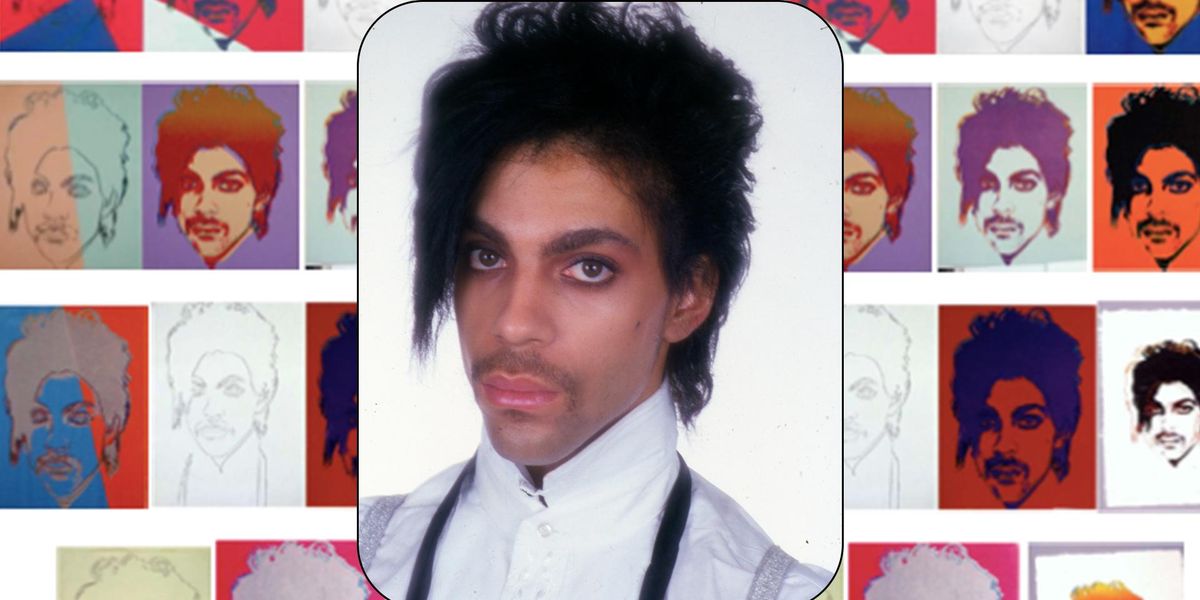

In 1981, Prince stepped behind Lynn Goldsmith's camera for a beautiful and vulnerable black and white portrait. Three years later, Andy Warhol manipulated the photo in his signature style, adding colors upon colors for a Vanity Fair cover. Almost four decades on, Warhol's reinterpretation of the photo lands on the steps of the Supreme Court in a a landmark case that could determine the future of fair use and copyright law.

Back in May, it was announced that an Andy Warhol copyright infringement case would be heading to the Supreme Court. However, this is not new. Goldsmith was made aware of Warhol's 16 silkscreen prints based on her original Prince photo after Vanity Fair republished one of them in 2016. A federal judge previously oversaw Goldsmith's case in 2019 and ruled in favor of the Warhol Foundation, arguing that Warhol made " "an iconic, larger-than-life figure" out of "a vulnerable, uncomfortable" Prince with the work.

A federal appeals court reversed the decision in 2021, acknowledging that Warhol's work retained many of the features of Goldsmith's original photo. The court also said it didn't matter if the images could be recognized and instantly attributed to Warhol, saying that "entertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labors of others."

In the 2021 reversal decision court documents, they note that "in 1984, Goldsmith, through LGL, licensed the Goldsmith Photograph to Vanity Fair magazine for use as an artist reference. Esin Goknar, who was photo editor at Vanity Fair in 1984, testified that the term 'artist reference' meant that an artist 'would create a work of art based on [the] image reference.'"

The Warhol Foundation stepped in, asking for the courts to consider Warhol's work as a commentary on celebrity culture and image and warning that ruling in Goldsmith's favor could have some slippery implications in the art world.

The case has now reached the Supreme Court, and the verdict seeks to answer the question of whether or not Warhol's work was fair use or if he violated Goldsmith's copyright. It's complicated, and the court will have to determine if Warhol's work could be considered entirely new. If it's determined to have been derivative of Goldsmith's original photo, the Warhol Foundation will owe Goldsmith millions.

Goldsmith argued that siding with The Warhol Foundation would set a precedent for artists to have their work appropriated without proper credit and compensation. Roman Martinez, a lawyer for The Warhol Foundation, posed the argument that ruling in favor of Goldsmith would effectively prevent museums, galleries and even collectors from displaying, selling, profiting off of and even possessing a lot of artwork. According to Martinez, "It would also chill the creation of new art by established and up-and-coming artists alike."

As some have pointed out, this could expand far beyond the art world. In a report from Gizmodo, ruling in Goldsmith's favor could impact how we use the internet. They compare the case to YouTube's copyright algorithm that automatically scans for music or footage that the uploader doesn't have the authority to upload. "Imagine filters that bring down the banhammer on any video that has a visual similarity to copyrighted material," Thomas Germain writes. "Sure, that would be an extreme outcome, but this is an extreme case. We’re talking about legally erasing the legacy of the most famous artist of the 20th century."

There are four factors to consider when determining if a work is under fair use or not. The first is the purpose of the work. Courts generally favor when the work is used for educational, commentary or research purposes, and it helps if the work is transformative. This means that just slapping your name on it won't do anything, and it has to be transformed enough into a new meaning or use.

The second factor is the nature of the work. Generally, the courts are more protective of creative works such as music, films and poems than they are with nonfiction works. The third factor, and one of the most dicey, is the amount of the original work used. There's no limit to how much or how little can be used, but it gets tricky when looking at photos because the full thing often must be referenced. While usually it can be found to be within fair use to use a small part of something such as a film or a book, it can violate fair use if one uses the "heart" of the work.

The final factor is the effect on the market, which is often the most complicated to determine. Does the copyright owner have an impaired ability to profit off of their work with the existence of the new work? If the new work is deemed to serve as a replacement for the demand of the original, it could possibly violate fair use. Obviously, both Goldsmith and Warhol's lawyers are focusing on the purpose and the market effect factors in defending their sides in court.

The Warhol Foundation is arguing that the prints significantly transform the original message of the photo. While Goldsmith's photo was just a photo, Martinez said that Warhol's take commented on "the dehumanizing effects of celebrity culture in America."

Naturally, the courts were confused. While the 2021 appeals decision ruled in favor of Goldsmith, they also said that "the district judge should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue. That is so both because judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective."

Goldsmith was not happy with that decision because the entire point of their suit was to address the meaning of the work and how that did not grant Warhol the right to use the original photograph.

Furthermore, if we take into account the fourth factor of fair use about the market effect, it doesn't bode well for Warhol. Goldsmith was paid $400 in 1984 by Vanity Fair to license the photo, which was initially supposed to be used for a Newsweek feature that never ran. The Warhol Foundation charged $10,000 for Vanity Fair to use the image in their 2017 tribute to Prince, which is how Goldsmith discovered her image was used without her permission. Goldsmith was not paid. Even if the original $400 licensing fee was adjusted for inflation, it's a measly $1,142.67 compared to the hefty $10k.

For some added salt to the wound, when Goldsmith reached out about compensation and credit for the 2017 Vanity Fair issue, The Warhol Foundation responded with a preemptive lawsuit asking for the court to recognize the work as under fair use. So you can understand why Goldsmith has decided to fight hard.

It's difficult to answer the question of what matters more: the artist's intention or how the audience perceives the art. Is that even up to the courts to decide? We'll have to see how this plays out.

Photos courtesy of Lynn Goldsmith/Getty and The Collection of the Supreme Court

From Your Site Articles

- Andy Warhol Copyright Infringement Case Will Go to the Supreme ... ›

- "The Andy Warhol Diaries" Spotlights His Queer Love Story - PAPER ›

- Andy Warhol's Trans Subjects Finally Get Named - PAPER ›

Related Articles Around the Web