Care

'The Aphrodisiac Kitchen' Is a Queer Coming-of-Age Cookbook for Healing

Story by Dan Q. Dao / Photography by Shaun Lucas

08 November 2021

"I think a lot of people are missing out on the romance of food," Andreas Carver says. "It's the story of going from earth to market to home, then creating something that will be your life force and your energy to move through the day. When you cook something for yourself or for someone, there's a bond formed."

Carver's romantic perspective on food is fitting for the title of his latest project, The Aphrodisiac Kitchen. The first installment of the cookbook, entitled "Volume 1: Departure From Youth," is Carver's reflection on past grief, a journal of healing and a statement of self-acceptance.

In a sense, it's a queer coming-of-age story, told through the lens of food, with its powerful ability to encapsulate memory and raw emotion through flavor and texture. "When I turned 27, I braced myself for my Saturn return... a second puberty —my becoming," Carver writes in an editor's letter. "The future felt very real and very long. I didn't know how to just be. I still don't, but cooking makes being present easier."

The 31-year-old chef and artist, who grew up in a half-white, half-Black family in North Carolina, says part of his connection to food has to do with a nostalgic association from being raised in the South. "I grew up around a lot of Southern cooks, a lot of female cooks," Carver says. "I always loved being in the kitchen with my mom and my grandma."

But Carver is cautious of suggesting that food is all cupcakes and rainbows. "Once I started to see food politically, I realized how so much inequality revolves around food and how different things could be." he says. "What if America wasn't so reliant on meat?" Carver himself has been plant-based for 16 years.

On the heels of a long career in the service industry, Carver initially launched The Aphrodisiac Kitchen as an online journal, which then became a pop-up dinner series. Finally, during the pandemic, Carver decided to create Volume 1, writing, styling and shooting all 100 pages of the book on his own.

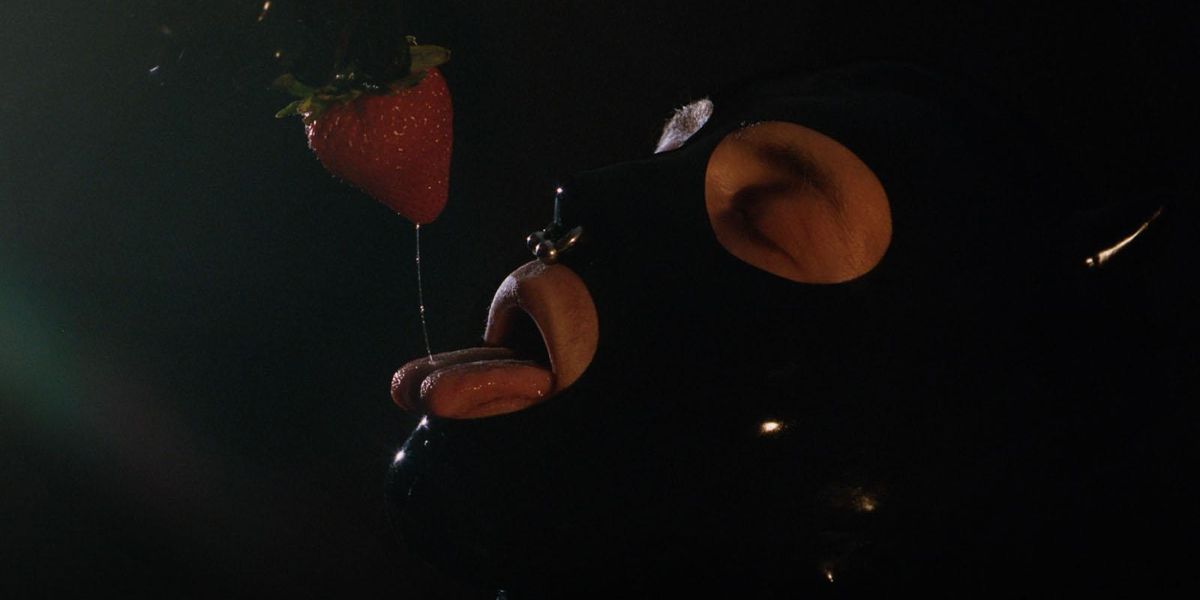

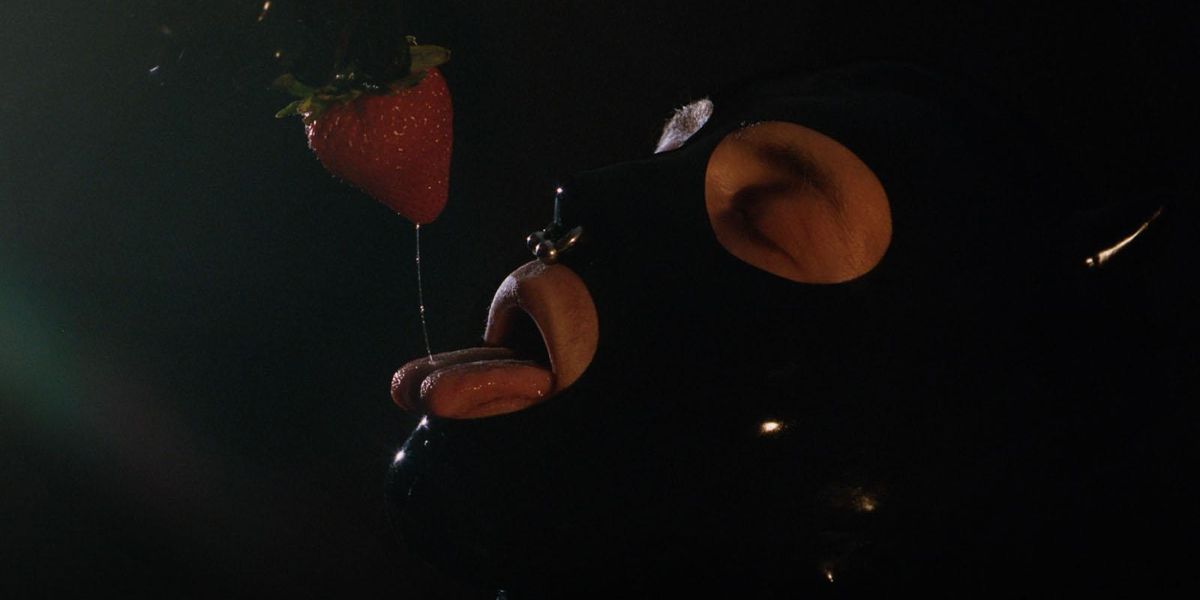

Standing in contrast to the fashionably bright, millennial girl-bossed lifestyle magazines of today, the book is admittedly dark and moody. Ahead of the table of contents, a dramatic full-page image of a latex-gloved fist crushing a plate of bursting cherries is at-once grotesque and sensual. "Pleasure and pain go hand in hand," Carver explains. "Can we ever feel happy if we are never sad? Can pleasure result in elation if we never feel pain? I wanted to play with that idea... plus I love latex and rubber."

Meanwhile, another section of the book, called "Across Our Faces" is a photographic representation of the grief felt by marginalized people during the Trump administration, with close-up images of fruits torn open, flesh ripped open and juice bursting, symbolizing the horrors of the era for queer people and people of color.

Yet, behind all the personal and political commentary is the simple message of healing, which Carver describes as a daily practice rather than a destination. As Carver suggests, the commodification of both food as "lifestyle" and healing as "wellness" robbed them of their interconnectedness. "Healing has also been commodified — it's now a destination," he says. "That's a very westernized feeling, but I think it's an ongoing process. You're always going to be working through it."

Juxtaposed against the themes of anxiety and depression, and the inherent political undertones of food, are Carver's intimate representations of his own personal identity as a queer, mixed-race chef who grew up in the American South — and his own personal development since childhood. An icebox sponge cake recipe, entitled the Legacy Cake, came from his great-grandmother, who he calls Maw-Maw. It's recreated here as a plant-based dessert.

"When I told my grandma I wasn't going to be eating it anymore, she couldn't believe it. She couldn't understand why I was making this extremely political decision," Carver explains. "She passed in 2019, so this cake is part of my legacy now. People might say it's blasphemy — to change a tradition that's been passed down like this — but I believe we have to question everything, even what we're given. That can mean shedding old ideas about race and racial equality, and it can also be as simple as reconfiguring a coconut cake."

First and foremost, Carver says he wants his book to be accessible to anyone in need of a connection to culture. Through recipes and imagery, his cookbook pulls at the heartstrings and reminds us of the most elemental pleasures of our favorite foods, and especially those with which we associate difficult memories.

"You don't need to be eating oysters or chocolate-covered strawberries," Carver notes. "When you cook with someone, there's something there that can be incredibly romantic. Food is romantic, no questions about it. Everything is an aphrodisiac — that's the point of The Aphrodisiac Kitchen."

Learn more about The Aphrodisiac Kitchen and shop "Volume 1: Departure of Youth" here.

Photography: Shaun Lucas