Rocket Ahuna Brings Hawai’i Fashion Into the Spotlight

Story by Mitchell Kuga

Apr 08, 2024

Towards the end of Rocket Ahuna’s debut show on March 22, staged on the second floor lānai that wraps around the ballroom of the Kaimana Beach Hotel in Waikiki, I noticed a woman sobbing. She turned her face away from the dress as if to shield herself from it, wiping away her tears. The dress in question was made out of a brown linen and corseted, forming the shape of a surfboard’s tip above the model’s bust. Four letters stitched across the nose of the board proclaimed its owner: DUKE. If you know you know, and for many guests in attendance — which included Evan Mock, stylist Taylor Okata, and local designers like Matt Bruening — the reference proclaimed an inherent knowingness, an image both cheeky and deeply Hawaiian.

What Duke Kahanamoku did for surfing, Ahuna hopes to do for Hawaiian fashion: cast an international spotlight on Hawai’i and Native Hawaiian culture. Born in 1890, three years before the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Kahanamoku grew up on the outskirts of Waikiki and lived in the water. He used his immense talents to introduce surfing, a cultural practice born in Hawai’i, to an international audience, winning three gold medals along the way as a member of the US Olympic swimming team.

“He was a sensation around the world and brought Hawai’i everywhere, and it was such a cool thing to me growing up,” says Ahuna, a recent graduate from the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, a few days after the show. “I resonate with that in a way. I look up to him. He is a moodboard for all aspects in my life.”

Ahuna’s show felt like a bold step forward for Hawai’i fashion. Over the course of 25 looks, it introduced a young, queer and mahū Kanaka Maoli designer who grapples with tension as a fertile ground for inspiration — between the beauty of traditional Hawaiian fashion and the New York impulse to innovate, between the Hawai’i for locals and Hawaiians and the fantasy version pre-packaged for touristic consumption, and between notions of the authentic and inauthentic and the various ways they blend, complicating what it means to be a designer making clothes from and about Hawai’i.

“A big goal of mine is getting people outside of Hawai’i to appreciate something that’s actually from here,” Ahuna tells PAPER. “I think that's what all of these tourist shops do well — all of these people who aren't from here buy these things, and I'm like, 'These things don't really represent who we are as a people.' We gotta substitute it and flip it and give people something real to understand, to love and learn about.”

The show started on Hawaiian time — not late, but right as the sun began to dip below the horizon of Kaimana Beach. Guests were given fresh flower lei upon entry, turning the air fragrant with expectation, and eventually took their seats facing the ocean. The percussive boom of a pa’u drum signaled the show’s first look: a loosely tailored brown aloha print suit worn open to reveal a matching bikini top. It was all constructed out of lycra, the stretchy material most recognizable as skin-tight beach attire in Hawai’i, but in Ahuna’s hands it had the fluid, silky sensibility of streetwear.

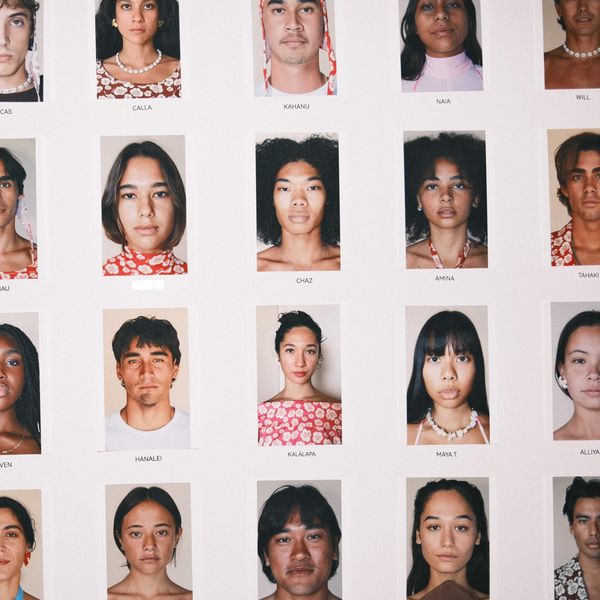

The rest of the collection — titled “KAIMANA,” which means the power of the sea — ranged from barely-there beachwear to voluminous bridal looks, and playfully riffed off traditional silhouettes in ways that felt both nostalgic and new. The models, who were all local and predominantly Hawaiian, strolled down the runway at a nearly glacial pace. “For the walk, I was pretty much like you're taking a stroll through Waikiki,” Ahuna says. “No rush. No rush at all. Everyone's just eating you up.”

The soundtrack helped. Composed out of a drippy, impressionistic jam session between musicians Lady Laritza La Bouche and Jonny Lam, it evoked a hang loose Waikiki of the '50s, all twangy steel guitar and swelling chord progressions on the piano.

He thinks a lot about camp when he’s designing, and though his clothes don’t scream it, they sometimes contain the sly suggestion of artifice ... a slight wink. Take his backwards, oversized pink Aloha shirt that appeared, head-on, as simply a fashionably slouchy dress. It was only when the model turned that the Aloha shirt revealed itself as something new, through the collar and oversized buttons running down her back. There were also multiple takes on the holokū, a loose formal gown popularized in 19th century Hawai’i, which he interpreted out of lycra and a very sheer cream chiffon, boasting leg-of-mutton sleeves and a train over a lycra bikini. The closing look, a pearlescent wedding dress topped with a swim cap, was made entirely out of neoprene, the stuff of wet suits. That space between tradition and innovation is how Ahuna says he’s come to process what it means to live in Hawai’i today — the constant negotiation between honoring and skewering what constitutes an “authentic” Hawai’i. “With this collection I wanted to make more authentic tourist wear and play off of those ideas — to have fun with the things that we interpret as ‘tourists’ wear,’” Ahuna says.

After the show, the air felt celebratory. Evan Mock praised the casting, noting that he knew more than half the models, and his brother Alika walked the show. “I'm used to going overseas [for shows] so it's nice to come back home and see people doing their own thing here and make a name for themselves,” he said. “To see all the aunties here, it was one of the favorite shows I've been to. It feels like home.”

Tory Laitila, the curator of Textiles and Historic Arts of Hawai'i, at the Honolulu Museum of Art, highlighted Ahuna’s attention to detail, like his use of floral-shaped coconut buttons. He timestamped the collection in the early Aloha wear period pre-statehood, between the 1930s and 50s. “That time of hapa-haole music, boat days, growing tourism, and the origins of lei day,” he said. “A few of the garments could have come off the catwalk in the '50s, but updated. It's a nice balance of classic cuts with a new take.”

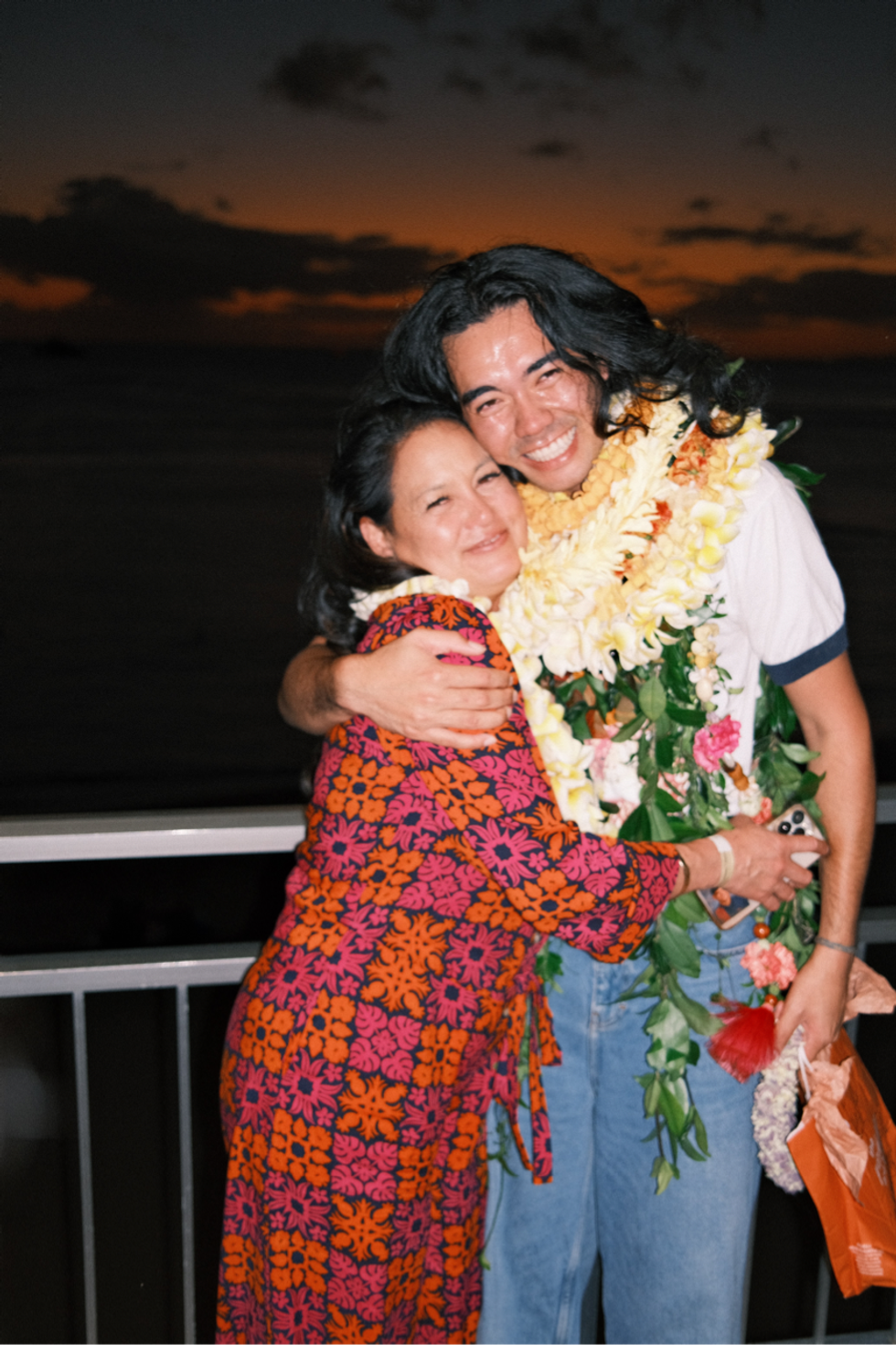

As for the woman who was crying? “That dress just took me back to the fact that my son honors our history, our Hawaiian culture. Why Waikiki is Waikiki,” Kanoe Ahuna, Rocket’s mom, told me with tears still streaming. “And by bringing that into his work, this creative world, he tells our stories. Our history is alive through our stories, and that's why I was so proud of him. Because it was Duke’s surfboard, it just told me he resonated with that history.”

Ahuna, who’s 22 and grew up in Kapa’a on the island of Kauai, designed the collection while in residency at Kaimana Beach Hotel, where he set up his atelier in an emptied guest room. He took inspiration from the surrounding area, taking long walks and sifting through the Hawaii State Archives for texts and images of a bygone Waikiki, which means “spouting fresh water.” Before developers transformed it into a playground for tourists, Ahuna was struck by how lo’i, or wetlands, separated Waikiki from Oahu’s interior. It was once the area where Hawai’i’s ali’i, or noble class, would come for leisure, and was the first capital of The Kingdom of Hawai’i from 1795 to 1796. Today, Waikiki is largely regarded by locals as a place for tourists, with the 3.5 square mile stretch accounting for 42 percent of Hawai’i’s visitor revenue.

The two-tone pareo-inspired Aloha print that frontloaded the show looked, at a glance, like something fun you might find at an ABC store, the chain of tourist-centric convenience stores that populates nearly every block in Waikiki. That effect was deliberate, but Ahuna worked with graphic designer Cait Tully to develop a print that showcased a flower endemic to the area: pua hau, which grew rampant on the hau bushes that populated Waikiki back when it was a wetland.

After graduating from FIT in 2022, Ahuna had plans to stay in New York, but after attending the Merrie Monarch Festival in Hilo last April, he decided to move home. His brother just had twins and he cherishes time with friends at the beach, but there were challenges to designing a fashion show from Hawai’i. Local manufacturers expressed confusion when Ahuna asked for French seams, and he often feels constrained by the firm traditions that guide Hawai’i fashion. “As a Hawaiian designer, it’s fun to live in a world that's so culturally rich, but it’s hard to modernize things while still being respectful,” he says. “Like how do I translate ulana lau hala but not piss off every Hawaiian weaver here in Hawai’i?”

Ahuna’s goal right now is to eventually move back to New York and design collections about Hawai’i for New York Fashion Week. He says it took moving to New York to fully reclaim his mahū identity — the Hawaiian word for someone who sits between male and female, who were traditionally the healers and keepers of cultural tradition—and he misses the independence and freedom he experienced there. But for now, he knows Hawai’i is where he needs to be. It’s where he’s cultivated his “fashion family,” a network of friends and family he relies on to bring his creative vision to life. “The critiques that I'm able to get here, from just my peers alone, is the most beneficial thing,” he says, adding that his professors in New York were understanding of his concepts but lacked the cultural foundation necessary to really push it forward.

When it gets challenging, Ahuna looks to his north star for proof of the possibilities of working from a remote island chain as a springboard to bigger stages. “Duke being a boy from Hawai’i and competing and representing on a grand stage for all these people, it's such a cool thing that I sit in awe of,” he says. “That is my goal right now, bringing Aloha to other places.”

Photography: Angelina Marie Lalaloopsie and Michael Voss

Related Articles Around the Web

MORE ON PAPER

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October

Music

You Don’t Move Cardi B

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

Story by Erica Campbell / Photography by Jora Frantzis / Styling by Kollin Carter/ Hair by Tokyo Stylez/ Makeup by Erika LaPearl/ Nails by Coca Nguyen/ Set design by Allegra Peyton

14 October