James Kelleher is more reserved than one might imagine a nightlife promoter to be. Soft-spoken and almost bashful when I meet him at 444 Club, a new bar in Bushwick that takes interior design inspiration from the queer auteur Gregg Araki, he gently asks if we can chat about the club's festivities the next day. He wants to clarify a few thoughts he had about the event, a drum-and-bass affair that kept a steady BPM around 165 while a smoke machine coughed out billowing masses of sweet-smelling fog. Kelleher, a former Democratic Socialists of America organizer, seems more comfortable talking about political activism than parties. But he's giddy about the event, which is slowly filling up as it nears midnight.

One could draw plenty of conclusions about the crowd that night, who largely lounged on beat-up Victorian-style couches strewn about the dance floor, occasionally jumping up to dance when a particularly nasty bassline took hold. But unless you had seen the event's Facebook page, it was unlikely you would guess the night's political motive: a fundraising effort for Chelsea Manning.

Related | SISTASPIN Is Making Nightlife More Black, Femme and Queer

The party at 444 Club is part of a growing trend among activists in New York's club community that seeks to harness the power of ravers to make real political change. Organizers of these events aim to connect their events' attendees to a larger purpose, whether it's direct aid to specific people and organizations or more nebulous ideas about challenging power differentials, and, ideally, to sow the seeds of political action outside the confines of the dance floor.

Plurletariat, a new zine whose name is a portmanteau of the trance-era rave mantra of "Peace, Love, Unity, Respect" and the Marxist ideal of a state run by a working proletariat class, hopes to manifest the intersections between these ideas through writing, "hold[ing] events in the real world when it makes sense," co-founder Sophie Weiner explains. Weiner started Plurletariat with childhood friend Zoe Beery after the two met likeminded leftists at Sustain-Release, an annual electronic music festival in upstate New York. After half-jokingly suggesting that they organize a "techno caucus" within the New York Democratic Socialists of America, they decided Plurletariat would be the best outlet for their burgeoning ideas.

Related | Club Chai Celebrates 3 Years of Community and Collaboration

Weiner is quick to point out the parallels between political organizing and underground dance movements: "Dance music was something that came from an incredibly grassroots place, and a place of people who are probably some of the most oppressed people in society — queer people, people of color, trans people."

And though Beery argues that Plurletariat's explicit connection of politics with dance music is fundamentally different from the inherent politics of the nightclub — "I don't think that there were tons of flyers on the table at the Loft or in the Gallery or in the Garage" — it's hard to ignore the history of explicit political action that has come out of New York nightlife, from the fundraiser for the AIDS organization Gay Men's Health Crisis held at the Paradise Garage in 1982, which raised over $50,000, to the recent initiatives to work with state representatives to overturn the city's "Cabaret Laws" that prohibited dancing at clubs without an expensive license.

At the Bushwick bar Mood Ring during the launch party for the first issue of Plurletariat's zine, there was indeed a table covered in pins and zines, as well as a donation box for the trans aid organization No More Dysphoria. But as with the Chelsea Manning fundraiser, politics seemed secondary to an ordinary night out; the bar was crowded, sure, but as a friend pointed out, it felt like "just a typical night at Mood Ring."

It remains to be seen whether buying $9 mate/vodkas at a Brooklyn nightclub is an effective mode of political engagement. Both James's party and the Plurletariat launch raised about $600 each — not anything to scoff at, but significantly less than similar fundraisers online. And as James later admitted after his party, the excitement around the event was hardly focused on the cause at hand: "A lot of people came because they love drum-and-bass and there aren't enough nights for that in Brooklyn."

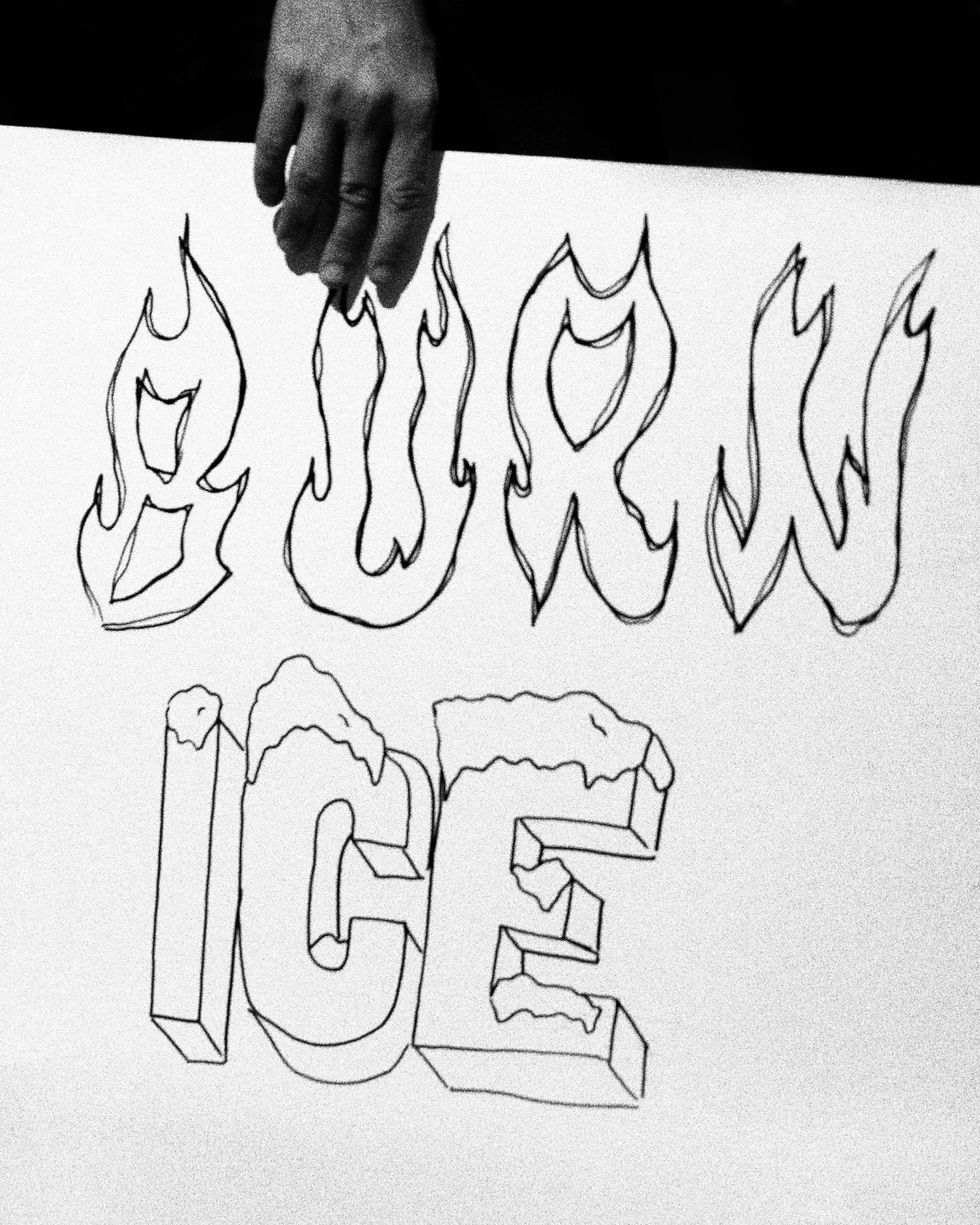

Melting Point, the brainchild of club organizer Brytani Caipa and photojournalist Eric Brian Stevens, stands out as the most fully matured of these recent New York-based activist endeavors. A pun on its goal, to snuff out ICE, the group was founded last year in response to President Trump's call for increased raids on undocumented immigrants. Feeling helpless but motivated, they wanted to harness their nightlife experience for a good cause. As Caipa puts it, "Throwing parties is what we could do."

Since their launch last year, they've thrown raves on a near monthly basis, raising over $16,500 for the refugee aid organization Al Otro Lado. They credit the fundraising success of their parties in part to the diversity in their lineups. Their New Year's Eve event, which drew over 4,000 attendees, placed techno stalwarts like Ne/Re/A on the same bill as noise artists like Kill Alters and avant-pop performers like Yves Tumor.

By bringing out more than just the typical "technoheads," in Stevens's words, they were able to raise funds from a much broader coalition. "Our goal is to unite the underground, unite these different scenes, expose them to different music, and make everyone aware what power there is in our numbers," Caipa says. "If all of these different communities can come together and realize how strong we are [together], we're capable of everything."

On a Sunday in late June, Melting Point held their first event outside of the confines of a sweaty dance floor: a "sonic protest" in Manhattan's Foley Square, across from ICE's New York headquarters. As puzzled tourists stopped to take in the sight of ravers thrashing to harsh noise in the middle of a scorching hot summer's day, it felt moving and even a little punk to witness such a disruption to the everyday lives of oblivious passersby.

But as Travis Morales, a representative from the anti-Trump organization Resist Fascism, took to the DJ booth to call for the rise of the Revolutionary Communist Party and sow a distrust in mainstream media outlets like MSNBC, his ideas felt disjointed from the optimistic spirit of the day. Stevens admitted beforehand they had failed to find a full panel to speak on immigration issues at the event; in general, the speech highlighted how even more fully formed organizations like Melting Point are still in their infancies when it comes to political organizing outside of the club.

Despite their shortcomings on a broader political stage, organizations like these still reinforce an essential collectivity that anyone who's spent 12 hours dancing among strangers can attest to. At the event, I met The 83rd, an organizer and DJ who was coordinating signage among protestors. They seemed a bit too chipper to be out in the 80-degree weather. Only a month prior, they explained, they were badly beaten fending off a group of robbers at the opening night of 444 Club, and sustained a concussion as a result. But when it came to hospital costs, "everybody came together," to raise money for their expenses through a GoFundMe. "The community raised $10,000 in a day," they said incredulously. Their story felt like a microcosm of the lofty goals of these organizations: In a world that can seem comically unjust, ravers have to turn to each other for resistance.

All photography scenes from Melting Point by Andrew Hallinan