Is Naomi Campbell the Most Powerful Person in Fashion?

By Christopher BarnardMay 11, 2018

There is a moment in Catwalk, a 1995 doc directed by Robert Leacock that follows supermodels Naomi Campbell, Christy Turlington, Carla Bruni and Kate Moss during the spring 1994 RTW season, where Campbell and Turlington are back in their adjoining rooms at a gilt-encrusted Paris hotel. Turlington, fresh off a flight, muses jokingly about the size of Campbell's flower arrangement versus hers (much smaller) and tosses off some suggestions for dinner: Room service? Japanese? Meanwhile, Campbell is bent over her phone on the brass bed in a printed caftan. "I need to speak to Si Newhouse," she says, at once languorous and commanding. "How can I speak to Si Newhouse?" Offhandedly to herself (and really, the audience), Turlington responds, "Go straight to the boss" — an observation, not in the least bit wry, as if to say, Yes this is my friend Naomi, who calls billionaire publishers like it's nothing, and then we're getting sushi after.

It's not clear what the phone call is regarding and it hardly matters in comparison to what it illustrates about the caller. Newhouse, at the time and until his death last fall, was the most powerful figure in fashion media as the head of Condé Nast, the publishing outfit that owns Vogue, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, and GQ to name a few. Campbell was 23, at the Everest peak of the supermodel moment, a few years on from George Michael's instantly iconic "Freedom! '90" video that she famously starred in. This visual clanged the era's beginning and was four years away from her friend Gianni Versace's murder in 1997, which marked the end of the supermodel.

One of the most well-known models and perhaps the most in demand that year, the image of Campbell on the horn demanding Newhouse is the picture of a young woman who knows what she wants and is sure as hell not afraid to ask for it. Of course it is all the more delicious given the sumptuous surroundings and jet set circumstances, but the unmitigated confidence of Campbell's entreaty is breathtaking. It is a key to understanding her continued preeminence not just in fashion, but the culture as a whole. She is herself a cultural touchstone of fashion, beauty, ambition, and more recently, power — a power she has amassed through many, many moments over the course of 30 plus years, much like the one in Catwalk. By pressing for what is hers, Campbell has independently positioned herself on par with titans.

Related | Naomi Campbell Remains On Top After 30 Years

In the last year, Campbell has been seen less on the runway or fronting campaigns but more often sitting down with major players in politics (Mayor of London Sadiq Kahn) or technology (Chief Designer of Apple) in her role as a Contributing Editor at Edward Enninful's British Vogue. And there she was in April addressing a stadium crowd at the memorial of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela (in black Dolce & Gabbana mourning lace and kerchief, no less). Which is to say, her position in the cultural imagination as a global figure, at home with some of the most influential people on the planet, or comforting a grieving nation from a dais, has shifted as of late. Iconic model? Yes, always and forever. But this new Campbell, a macher on the world stage, is a stirring development.

Campbell's rise in the '80s from a child performer (she appeared in music videos for Bob Marley and Culture Club) to her supermodel moment later in the decade is now legend. Discovered by an agent after school in London, she landed her first cover the same year she turned 16. Through the churn of the fashion came a pivotal and life-changing introduction in 1987 to Azzedine Alaïa, the mercurial Paris designer known for his peerlessly crafted body hugging designs. The two were mostly inseparable until his death in November 2017 at age 82. Campbell called him Papa and he was her protector, champion, and unofficial costumer. Their relationship was familial (she had her own room at his Paris home), but also a crucial one in the trajectory of her career. Both were iconoclasts in fashion; one a designer who challenged the establishment, often running afoul of the powers that be with his disregard for industry calendars and hierarchical niceties. And she, someone who challenged traditional standards of beauty and what was considered commercially viable at the time.

Cases in point: Campbell was the first black model to be on the cover of American Vogue's September issue in 1989 (Anna Wintour's debut September issue), and the first black model ever on the cover of French Vogue (August 1988). These moments were hardly the result of dumb luck, though the latter being greased by YSL famously threatening to cut ads from the title if Campbell wasn't given a cover. Alaïa and Campbell were each other's biggest champions and something of the ultimate insider/outsider pair. They were part of the game, but would only play on their own terms. For instance, when no Alaïa looks were included in 2009's Met Gala "Model As Muse," Campbell boycotted — a reaction to the perceived slight of the event's host, Wintour, whom the designer was not timid about sharing his thoughts on through the years. He in kind came to Campbells rescue in 2012 during a harrowing assault in Paris just outside of his studio, the ballast of their bond being a safe harbor for both through the ups and downs of their lives.

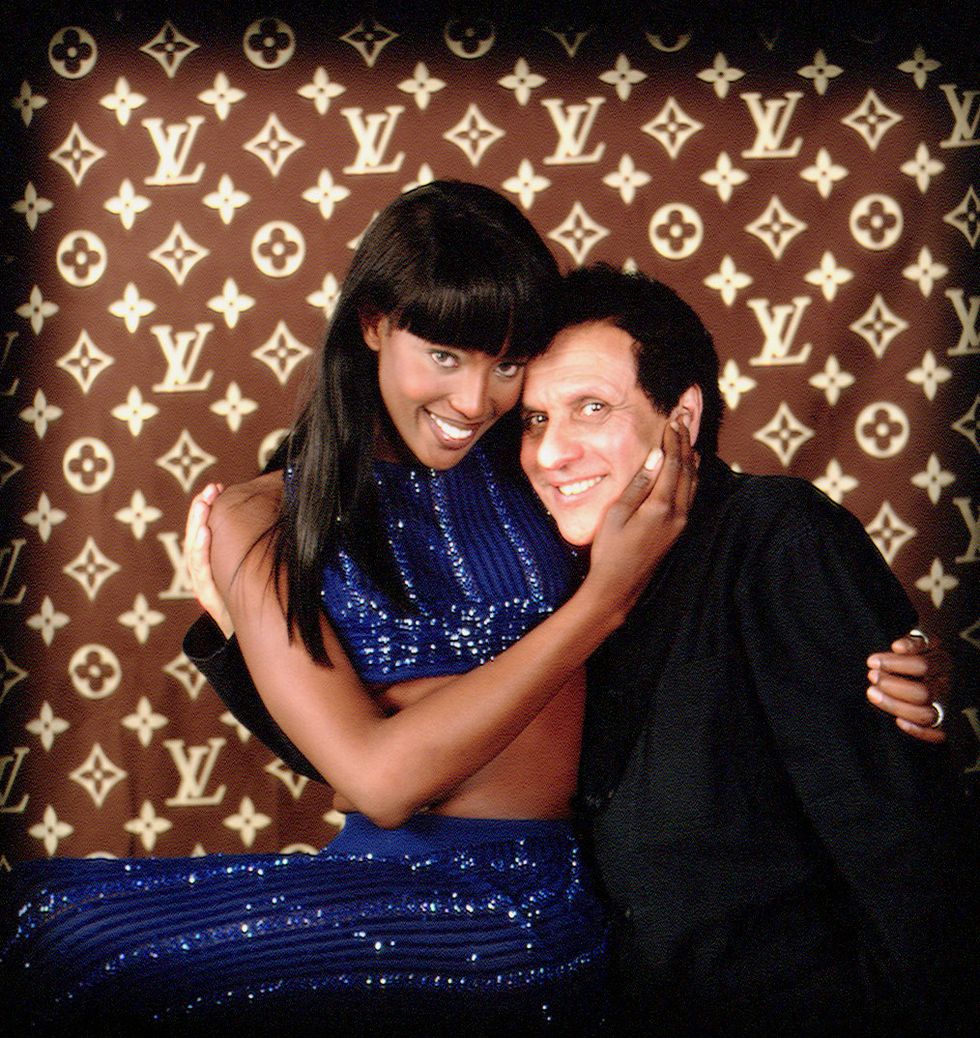

Naomi Campbell and Azzedine Alaïa

Since the designer's death, the public mantle of his legacy would seem to rest in Campbell's hands. Her moving tribute to him at this year's British Fashion Awards and candid sit down with Tim Blanks positions her as the ultimate authority and steward of the dearly departed fashion icon. There is simply no one else more qualified.

Related | Virgil Abloh's 'Aggressively Creative' Agenda

The closeness of that relationship, and the understanding of what it was like to be in the inner sanctum of arguably the greatest designer of our time is something Campbell has brought to her own championing of burgeoning design talent. She can spot a winner and when she does, she is unwavering. Fledgling designers she has shepherded range from the now household (Galliano, Tisci, McQueen, Posen) to the relatively new like Brandon Maxwell and Virgil Abloh of whom she said, "[He is] our new genius of the next generation that is going to carry us way into the future." Bernard Arnault would agree. Which is not to leave out established designers' whose brand identities are inextricably intertwined with Campbell's (Versace). Her donning of an upstart's creation can open doors for a designer overnight, due partly to how well her body could make even a burlap sack fly off the shelves, but also owing to the tacit understanding that she above anyone else knows what talent is, having spent so many intimate, hand-to-form hours with the greatest couturiers of our time. This power can only come from being in the room where it happens for as long and fruitfully as Campbell has.

But there is a curious paradox in the fashion world. To remain relevant within it, one must eventually be successful outside of it, as well. So it was, after decades as the platonic ideal, for better or worse, of a fashion model, Campbell found miraculous success in a bounty of delightful, if at times self-parodying, roles on American television. In Ryan Murphy's AHS: Hotel, Campbell played a fashion editor, Claudia Bankson, who meets a bloody end. She subsequently stole scenes in Lee Daniels' Empire as Camila Marks, a duplicitous vamp who after pulling off a Dynasty-style corporate take over meets (again) a tragic end. Daniels also cast her in his new series Star opposite Lenny Kravtiz and Queen Latifah where she plays the alcoholic mother of the title character. And just last month she had a role in Amy Schumer's I Feel Pretty as a bemused cosmetics executive next to Michelle Williams. These spots expose her to an audience, perhaps already familiar with her face and talent on the runway, in addition to a new generation of pop culture consumers. That's not to mention Campbell was already a Beyoncé lyric and the lead in the video for Jay-Z and Pharrell's 2003 collab "Change Clothes." Oh yes and her 2003 franchise model competition series on Oxygen, The Face, which produced at least one quotable tagline, the hallmark of any reality show worth its guilty pleasure salt.

But returning to fashion, one could argue Campbell's most important work has always been off the runway. In 1991 Time Magazine chose her to represent the supermodel moment (in Isaac Mizrahi) and in the accompanying interview is one of her earliest on-the-record statements about the disparity in representation and pay between models of color and her white counterparts: "I may be considered one of the top models in the world, but in no way do I make the same money as any of them," she said. Campbell has worked tirelessly to rectify this imbalance, and the industry is only addressing it — buds from a seed she determinedly planted nearly three decades ago. In 2013, Campbell, along with industry vets Iman and Beth Ann Hardison formed the Diversity Coalition, a group that vowed to call out designers and brands that consistently use only one or no models of color on their runways. Slowly but surely the results have been felt and seen in runways in New York and London with Milan and Paris typically, and conspicuously lagging . Also the somewhat glib, but necessary, practice of tallying runway shows for diversity ratios has become a tool against the industries penchant for white washing and one more prevalent after the formation of the coalition. Campbell made good use of a picture of the outgoing, and predominantly white, British Vogue team last spring, saying she is looking forward to a more "inclusive and diverse staff" under Enninful. Before Diet Prada there was Naomi Campbell.

As a marquee contributor at Enninful's British Vogue she has a larger, more consistent platform to push for the changes she has been demanding since her early years as a model. Together they are already leaving in the dust the whitewashed Vogue of yore and reflecting what the world actually looks like. Other masthead contributors at the title are makeup artist Pat McGrath, model and activist Adwoa Aboah, and director Steve McQueen, which feels like something of an Avengers team but for fashion. Is there any more apt example of #BlackExcellence than in the very corridors of Vogue at present? And what with rumors that Enninful is the likely successor to run American Vogue when Wintour steps down, the recent wave of change in London would only gain steam at the New York flagship. If there is any question as to what fashion will look like post-Wintour, it is happening already, and Campbell is gleefully at the center of it, hashtagging and storying with the earnestness and aplomb of Gen Z.

Campbell's sustained eminence inside and outside the fashion world should come as no surprise. She diversified like any smart business and resolutely fought for the people and issues she loved, well before they were popular or in the public conscience. A lifetime in an industry known for its disposability and caprice is one thing, but to now be setting the course for the future after 30 years is a wonder.

In Catwalk, the scene in the Paris hotel with Turlington fades before we get to see if Campbell is patched through to "the boss" in the end. But it is of little consequence in the intervening 25 years, because she's been the boss this whole time, we're only just now dialing in.

Photos Courtesy of Getty/Splash Illustration by Duhrivative