Naoki Sutter-Shudo Sculpts What Can't Be Said

By Harry Tafoya

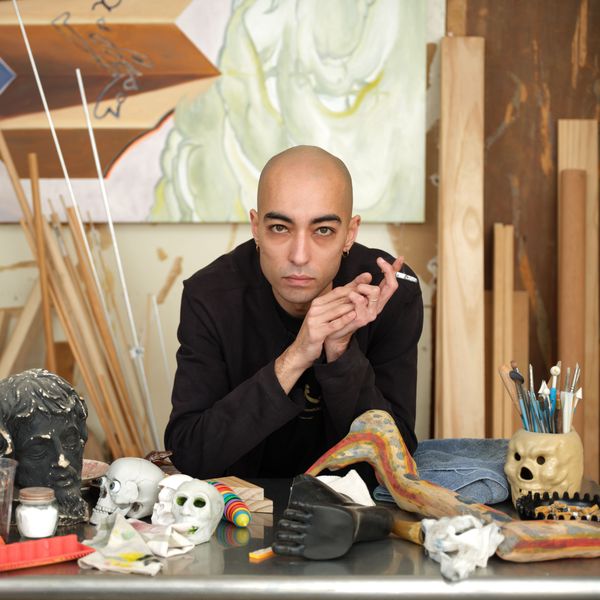

Mar 29, 2024Naoki Sutter-Shudo is fluent several times over. The Paris-born, Tokyo-bred, Los Angeles-based artist has a grasp of sculpture, painting and photography that’s as easy and sophisticated as his command of English, French and Japanese. But in acquiring these wildly diverse tongues and toolsets, he’s also developed a deep sensitivity to the subtle shades and distinct forms that an idea can take on, knowing just how easily they can get bent out of shape or lost in translation. But rather than spiraling over the basic inability of humans to ever fully understand one another, Sutter-Shudo has taken on the challenge of actually building out and coloring in the spaces where communication fails. In his wide-ranging creative practice, the artist has created a rich visual vocabulary to spell out concepts that are too elusive to put into words, circling over gaps in meaning and even giving structure to the void itself through woodwork, metal and paint.

In his recent shows at Gaga/Reena Spaulings in Los Angeles and Derosia in New York, Sutter-Shudo mixes wildly different styles of artwork from kinetic sculptures with molded-over doll heads to spiky crown of thorns sculptures to blown-up paintings of Bic lighters and the Hawaiian flag. Sutter-Shudo has a magpie’s eye for shiny rubbish and a relaxed intelligence that’s both sharply critical and responsive to the more abstract pull of material, color and form. He is a prolific collector of everything from rare books to cigarette packs to pictures of Paris Hilton; in a similar way, the conceptual thread that unites his portrait of far-right Playboy model Pierrette Le Pen with his riffs on Zen Buddhist calligraphy is more intuitive than rigorous or academic. There is a logic to how he assembles this series of work, but it’s open-ended, elliptical and at peace with not fully making sense.

Among Sutter-Shudo’s greatest gifts as an artist is a tolerance for contradiction and paradox, which lets him sit back and channel the absurdity of his work rather than bending over backwards trying to map a sense of reasoning onto it. The fabric-painted mantras that kicked off his show at Derosia — “form/void,” “nothing nothing nothing,” “the enigma of the universe” — are meditations that are clearly taken to heart. The architecture of his sculptures is structurally sound, but also builds out onto weird vistas and bizarre easter eggs. If you were to light the fake candle wick attached to “Untitled” (2024) you would probably end up burning the whole gallery down. A free-floating flame pops up attached to another work a couple of paces over, although the craggy aluminum bears more of a resemblance to a butt plug than a spark. All manner of surrealist knobs are attached to Sutter-Shudo’s work, both graphically striking (some of his art is a dead ringer for Memphis design) and freakily suggestive.

In a piece like “Pay Here (197 Grand St. 2W NY NY 10013)” (2024), Sutter-Shudo turns the audience into a kinetic sculpture, instructing them to pay into a coin slot without getting anything in return. It’s the kind of object-as-prank that Marcel Duchamp would approve of, setting the viewer up for a deadpan anti-climax. This works as a comment on the many fake and pointless transactions that define the art world (you might consider Maurizio Cattelan’s banana to be a cousin), but is even better as an illustration of how Sutter-Shudo cultivates meaning: by staging silly and stylish encounters with the ineffable.

PAPER caught up with Sutter-Shudo to discuss paying your way in the art world, the meaning of the shape of words and why Paris Hilton is so hot.

Could you talk a bit about your approach to language and how it becomes the jump start for the ideas you want to work with?

I grew up in Japan, with a Japanese mother and a French father, who spoke to each other in their own language. My mom would say something in Japanese, and my dad would answer in French, and I was in the middle of that, which was great because I naturally picked up both languages. Usually the kids of binational couples have one dominant language, but I didn't really have one. On some level, being between languages, which is kind of being between identities, you're forced to translate. I would pick up nuances of something that my dad would say that my mom wouldn't get or vice versa. But sometimes you are confronted with things that are untranslatable or very hard to translate. And I like thinking about these sorts of conundrums, almost like little intellectual puzzles, which in a way is similar to looking at art or thinking about art. The way you structure something physical, like a sculpture, or even a painting, can be similar to grammar or syntax. I'm into puns also, like that sort of slippage of language, when language becomes inadequate to describe something.

The gesture of language goes a long way to communicate itself. When you have language that you want to focus on, how does that dictate the shape or color of it?

Sometimes the embellishment of a word, or putting a color onto it, or having it be in a specific shape also does color the meaning of the word or add something to it, which is almost like creating a sentence out of one word. I like it when just the pure formal description of an artwork — like I'm trying to do right now — is also hinting at some meaning, or the meaning comes from the description comes from the physical aspect of the work. What's interesting about Chinese calligraphy is that originally those characters were written in a way in where the gesture created the meaning, meaning if you trace the line upward that means "up" and if you trace a line downward, that means "down." Even if the result looks the same, the brush stroke itself indicates the meaning, so the trace of the bodily gesture is already constructing meaning and, perhaps, symbolism.

Your approach is very associative. When people hear about these kinds of crossed visual wires, they often think of synesthesia. Could you talk about handling these words? Do you also have a visual sense for what they are?

I don't really have synesthesia, so not necessarily, but even when I write short stories, for example, I like to write by hand, the first draft. And there is something in the speed of the hand, that sometimes it's faster than your brain, which is, in a way, getting lost in the words themselves. I read in French, English and Japanese, but Japanese is the language in which I read the fastest because you don't have to spell out words in your mind as you're reading, you just kind of scan the page, and you get the meaning immediately. There are obviously characters that I like more than others for their shapes, because there's thousands of them, and stylizing them is an interesting thing that's been done for millennia. It's often very difficult to decipher old calligraphy when you read it, but trying to decipher something, even if it's just one character, is not unlike looking at art. Sometimes people who are not familiar with contemporary art or modern art assume that art is like a puzzle to be solved. You have these symbols, and then you have to decode them. But it's not like that. There's a quality to language and art that escapes being just a puzzle.

What inspired you to make the more abstract sculptures? Are they building off those same ideas you'd been working from, or are they coming from somewhere else altogether?

Sometimes it originates from pure play in the studio when I'm just assembling shapes and materials, and it's a quite slow process of assembling and collaging things, and then I just know what feels good or what feels true. It's not like meditation because you're active, and you're moving around the thing with sculpture. But there is something like a pursuit of truth, I'm not sure how else to put it, it almost feels religious at times. Almost as if there's something that you can tend towards, a perfect shape or something that is specific and feels good. But other times, it's also informed by more abstract [things], like design elements that you encounter in the world. When a shape starts resembling a potential symbol — that's when maybe it's interesting. It's a sort of interesting thing that's similar to maybe reading or writing.

You have other sculptures made for the show, like the coin slot, that initially seem to have a lot less to do with language and a lot more to do with how you're interacting with that space. Where did the inspiration for those sculptures come from?

The payment one, which is this very simple coin slot that says “pay here” on the side — “pay here” being a phrase that you encounter a lot, especially when you're driving in Los Angeles and you go to park your car or something. And, you know, it's just like, I'm just trying to exist and breathe, but everything is like being monetized and you have to pay for everything. There is a masochistic pleasure in getting rid of money. Like it's probably going to remain there forever until the building gets torn down. And then who does the money go to? Does it go to the landlord? The landlord probably doesn't need any more money. But there's a sort of perverse pleasure in submitting yourself to something that is already extracting money and wealth from you. Also, just taking money out of circulation and having it disappear. Because there's no reward: when you put the money in, it disappears, it doesn't do anything. You don't get anything in exchange. And that's a big trap. It's also rare to pay for nothing.

It feels very art world-specific, because so many of the transactions that go on in the art world feel like they're paying for nothing and actually what you're buying is just pure abstraction.

Oh, totally. I mean, like works that are bought and sold without even leaving the storage.

Or without even being seen.

Most sales today are online. And people use these weird euphemisms. Like: "We just placed this work." But like, was it placed? I'm not sure. Is it in a place? Or is it in Delaware? It was funny, seeing the reaction of artists and dealers in front of that piece. Like Gregor Staiger, who is a dealer from Zurich, kept putting in coin after coin and said, "Metaphor for my life, metaphor of my life." It’s a weird humor thing.

The Swiss love to do all kinds of weird, metaphysical things with money. You're a pretty prolific collector. Could you talk about a couple of things that you collect?

My collecting is not informed by any guidelines. What I'm interested in is just like being in the world and encountering something and appreciating the thing for its thing-ness. I like to go to flea markets, antique stores, and just, you know, anything that catches my eye, regardless of its value. So it could be old ceramics or lacquer-ware, but it can also be just like a screw or something. Trash sometimes, also — I have quite a bit of trash that I'll just find on the street. I'm also very bad at throwing things away. I keep, for example, all the packs of cigarettes I smoke, I keep them in a box.

Wow! How big is it?

I have several boxes of them. I started doing that only a couple years ago. But also, I started keeping cigarette butts in buckets. I collect a lot of books, and, you know, it used to be just books for the content of the book, but now it's becoming slightly more bibliophilic. Recently, I got some books from George Bataille's private library. I have a binder full of magazine clippings of Paris Hilton.

Why is Paris Hilton of interest to you?

Paris Hilton was so big when I was first exposed to American pop culture — and the fact that she was famous for being famous. You wouldn't have Kim Kardashian without Paris Hilton. At the time, it was so hard to foresee the influence that she would have or how she would pave the way to fame based on nothing. It's like pure fame. And this pure invention was a weird camp character. And had I known that, I would have been critical of it at the time.

Do you like Paris more as a person or as an object?

As an image. I would not really care about meeting her. But yeah, just as an image.

That seems to be a common thread for so much of this work, it seamlessly navigates all of these different dynamics: it's traditional but it's modern, it is reverential but it's also kind of silly, it's appreciative but also kind of critical. But you're also somebody who is coming in at the nexus of these two very distinct cultures, which are both incredibly rich and, to be blunt, quite racist. How do you feel like growing up between these cultures helped form your perspective? Was it a sense of "both and" or "neither nor"?

It's funny, often people are like, "Oh, it must have been hard growing up in Japan for not looking fully Japanese,” or something, but not to me. I never felt any problem with it or felt singled out. There's this Baudelaire poem that starts out something like: "Life is like a hospital, where every patient says that by the window is nice, but it's too cold. But, like, I also want the view by the window.” And at the end: "It's anywhere, anywhere out of this world.” Like you don't know where you actually want to be. And that's how I feel most times. I don't really know where I want to be or where to be.

Being in Los Angeles is a neutral, weird territory, it has extremely new history. It has its own history also — but it's sort of a neutral zone. But yeah, I mean, it's like how people have different personalities in different languages. And I do feel that a lot when I'm talking to someone in French, or talking to someone in Japanese, it brings out a different way of being, it brings out a different way of thinking, also. And it’s a way for me to not fully commit to one thing — but also, not being able to commit to one thing is perhaps why making something ambiguous in the form of an artwork is a good outlet.

Photos courtesy of Paul Salveson, Gaga/Reena Spaulings and Derosia

Related Articles Around the Web

MORE ON PAPER

Entertainment

Dove Cameron and Avan Jogia Broke Their Molds

Photography by Gustavo Chams / Story by Joan Summers

Photography by Gustavo Chams / Story by Joan Summers

18 February

ATF Story

Madison Beer, Her Way

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

Photography by Davis Bates / Story by Alaska Riley

16 January

Entertainment

Cynthia Erivo in Full Bloom

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

Photography by David LaChapelle / Story by Joan Summers / Styling by Jason Bolden / Makeup by Joanna Simkim / Nails by Shea Osei

01 December

Entertainment

Rami Malek Is Certifiably Unserious

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

Story by Joan Summers / Photography by Adam Powell

14 November

Music

Janelle Monáe, HalloQueen

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

Story by Ivan Guzman / Photography by Pol Kurucz/ Styling by Alexandra Mandelkorn/ Hair by Nikki Nelms/ Makeup by Sasha Glasser/ Nails by Juan Alvear/ Set design by Krystall Schott

27 October