In complete contrast to its contemporaries (read: Disney and Pixar), almost all of Hayao Miyazaki's films have centered on adolescent girls fighting through a male dominated world to get what they want. From rescuing the guy, finding independence, to just being an overall badass, Miyazaki's ability to infuse hidden messages of environmentalism and women's rights into films that are meant for children is likely the exact thing that continues to draw those same now-adults to it, 10 years later.

In my mind Hayao Miyazaki has always been the greatest animator of his time. Spirited Away changed my life in every imaginable way. Raised by a single mother in a house that was predominantly matriarchal, Studio Ghibli for me was a reflection of how I saw the women in my house and in my life: women that were fighting (and winning) daily battles, both internal and external, as well as thriving despite circumstances. Miyazaki reinforced to middle school me that I should not take any shit, and taught me how.

Related | Jordan Peele Is the First Black Winner of Best Original Screenplay

In 90 percent of Ghibli films, romantic love is never the driving plot of the story. That is not to say Miyazaki shies away from the idea of romantic love, nor does he promote the problematic trope that depicts romantic love as a kind kryptonite for strong female leads. Rather, his films always keep a balanced and very much real life depiction of male and female interaction. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind defeats the stereotype that romance is the problem-solver for all female struggles, eclipsing the idea that women must be saved by any kind of knight in shining armor — without being preachy. "I've become skeptical of the unwritten rule that just because a boy and girl appear in the same feature, a romance must ensue," Miyazaki says. "Rather, I want to portray a slightly different relationship, one where the two mutually inspire each other to live – if I'm able to, then perhaps I'll be closer to portraying a true expression of love."

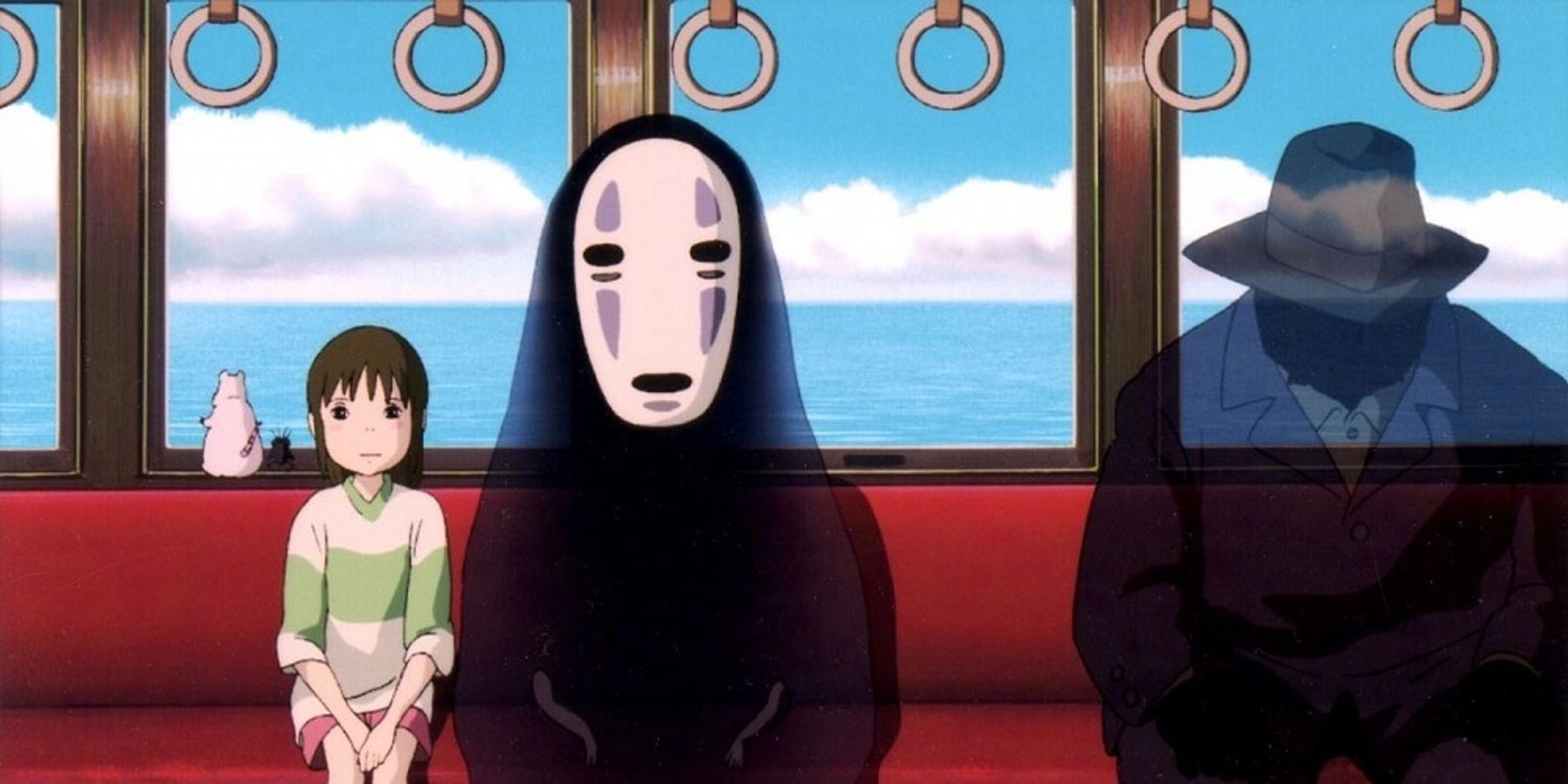

The first Miyazaki film I ever saw, Spirited Away, was a jello mold for most of my childhood and one of my first memorable adolescent nostalgia checkpoints. From elementary through high school (and yes college) watching this film was a right of passage. Anyone who came over my house was forced to watch this on DVD, as I watched them react to every single scene, making sure they laughed and cried at the right parts (the price to pay when watching a film with any Pisces, ever). Unlike Disney, many of Miyazaki's films don't center around an all-evil villain. The antagonist is only singled out once they've identified themselves as a threat to the heroine's own sense of independence. Never are they stomped out with violence or death, rather internal reflection and self-betterment from the heroine. Such is true in the case of the relationship between Chihiro and No Face in Spirited Away. Miyazaki explains the heroine must operate in an environment where "the good and bad dwell together."

"She manages not because she has destroyed the 'evil,'" he explains, "because she has acquired the ability to survive."

Related | Lena Dunham Reveals Donald Glover Felt Tokenized On 'Girls'

At 13 years old, Kiki, the central character in Kiki's Delivery Service, tells her parents that she's going out to become a witch at midnight. With no plan, and now, no parents, she still leaves in full confidence that somehow, she'll make it work. The film speaks to the fear of transition in all of us: whether it's moving to college, graduating and entering the workforce, or starting anywhere new, we all have fear the unknown. A heroine who has zero traces of self-doubt sure is an ideal figure to watch.

Watching Disney and Miyazaki films during the same developmental period, I experienced a simultaneous internal re-wiring of all of the classic damsel-in-distress narratives that shaped us when we were young. Miyazaki was the only one to subtly probe gender binaries and representation: the men were no longer the warriors...women were. In Howl's Moving Castle, though Sophie and Howl are romantically linked, Sophie saves and rescues Howl at the movie's climax. Again, her love doesn't come in the form of a savior, nor is it a focal point. Miyazaki is one of the first animators to write stories about women of color in which there is no tragic trope preset, no man to swoop in or give an ultimatum. He recently announced he will retire for the 5th time after the release of his last film, How Do You Live?, but for a man whose work has impacted a whole generation of women across the globe, there is never any retirement.

Image via Youtube

From Your Site Articles