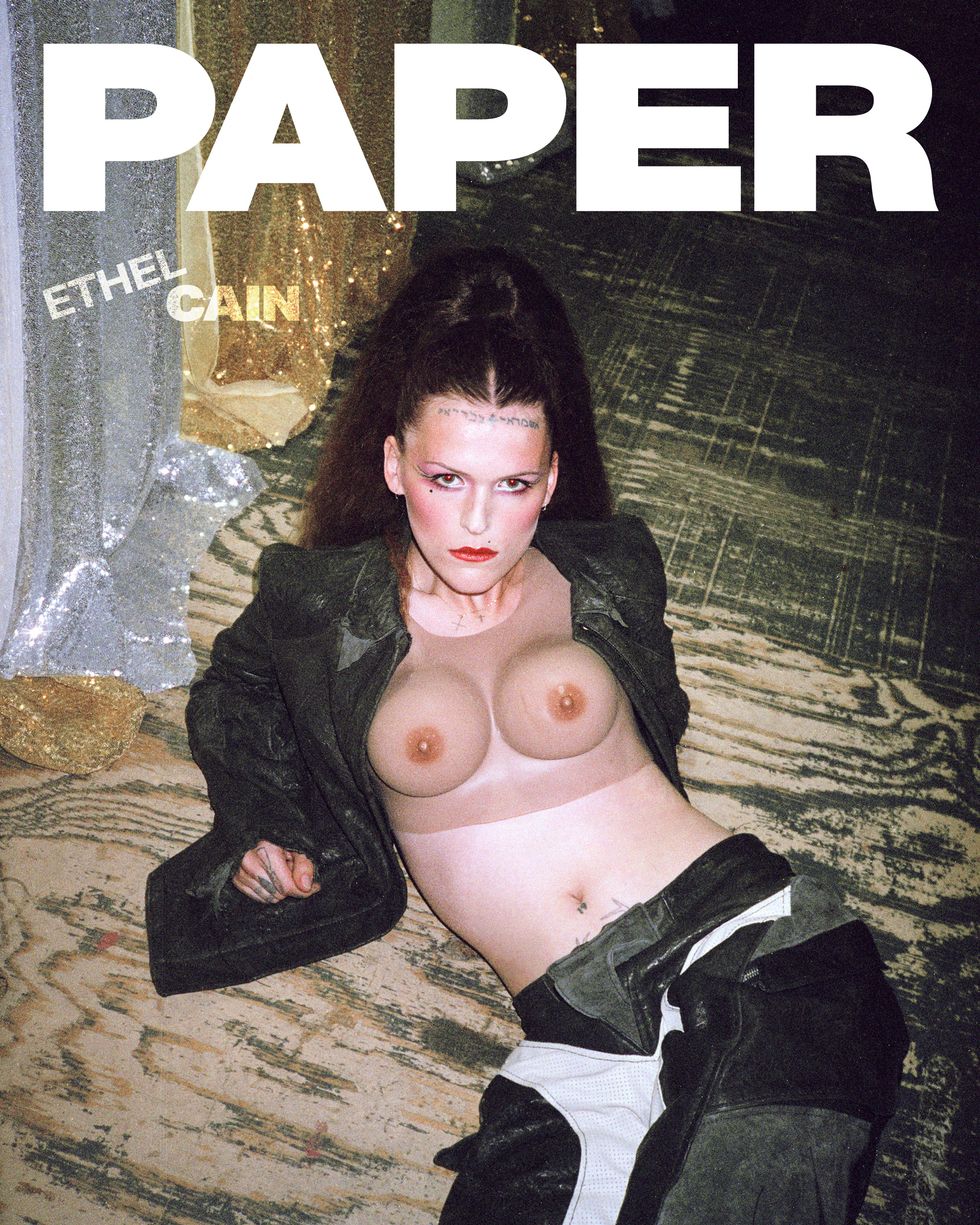

Music

Ethel Cain: All-American Girl

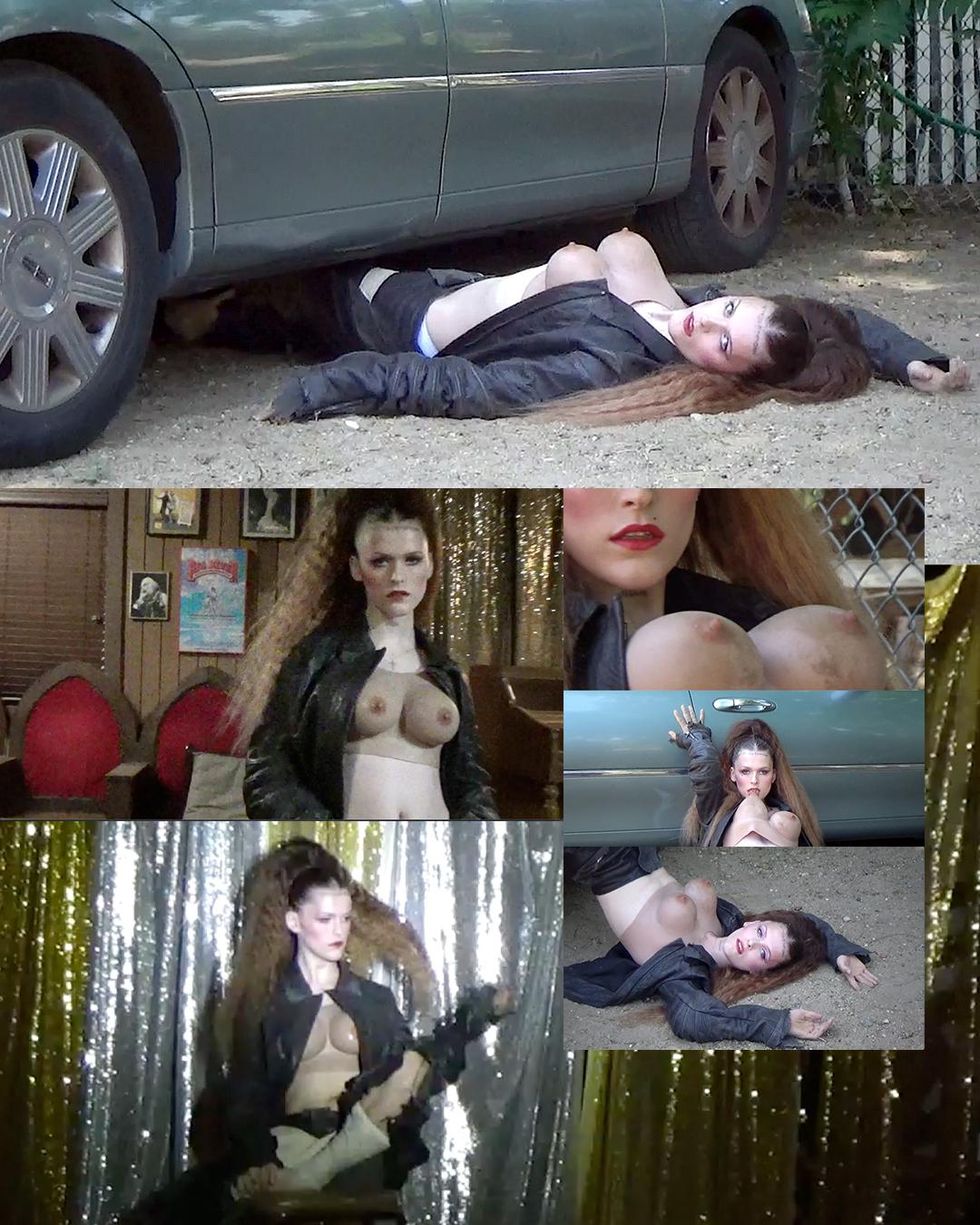

Story by Jacqueline Codiga / Photography by Moni Haworth / Styling by Joanie Del Santo / Hair by Rob Talty / Makeup by Nick Lennon

29 June 2022

"I spent a lot of time with my dad when I was really little.'' Hayden Anhedönia, known by her prairie girl-next-door alter-ego Ethel Cain, is sitting in her wood-paneled bedroom, framed by a tattered American flag that she found laying in the dirt next to an abandoned roadside fruit stand. She is recalling a memory from her childhood in rural Florida, but unlike the dark, brooding tragedies she sings about on her debut album, Preacher’s Daughter, the picture she paints is an idyllic one.

"We would go fishing, we would go hunting, we would go for walks," Cain says. "He would wake me up at like four or five in the morning, so we could get started early before he would go to work. And I remember the way that air would feel at the beginning of a brand new morning, like the way that the sky would be pink and blue and green and the way that the air would be cool. I remember thinking that was the most magical time of day because it's like, I have the whole day to do something."

Jacket and pants: Worstok

Much of Preacher’s Daughter evokes these liminal spaces: the tranquility of the moment just before daybreak; the relief at dusk as the brutal Florida sun finally dips below the horizon; the seconds of silent anticipation as two people lean in for a kiss. For as much as Cain has to say in this ambitious 75-minute project that tackles themes of family, faith, love and abuse, some of the album’s most interesting moments are when nothing is being said at all — from the chirping crickets on "Hard Times" to the buzzing flies of "Ptolomaea."

These seconds of stillness make way for stakes that feel even higher, given the stark contrast. Nature’s calm is countered by Cain’s tales of grisly violence, over-the-top melodrama and Americana clichés. "I love art that is a slightly dramatized version of real life," she explains. "Just like a regular day going strangely right, or incredibly wrong. When you grow up in the South, it's like one long, hot day forever and ever, and you're waiting for something to happen. That's what I want my art to be: waking up on a day where a lot of things are happening in a place where things don't usually happen."

Cain is from Perry, Florida, a small, swampy, town in the panhandle; a choir girl born the daughter of an actual deacon. The plot of this album obviously draws parallels to the singer’s real life, but the difficulties of her childhood were much more mundane than the lurid stories in her music.

Immediately after Cain recalls those early mornings, a more bittersweet memory comes rushing in. "I always loved being outside," she says. "I remember some of my favorite moments in church would be sitting and being so antsy and waiting for the service to be over... rarely would it go over an hour, but it always felt like the longest thing ever. Then, they would set up tents under the oak trees on the green outside the church, and everybody would set up their tables and tin foil dishes full of food. You would run out with your friends, in and out of tents, and you would play tag and climb trees and hear people talking. It was so lively."

Jacket and pants: Worstok

Jacket and pants: Worstok

She continues, "One of the things I came back to while making this record was not only those feelings, but the juxtaposition of what it felt like to lose them and not have them anymore — the nostalgia of remembering them and how beautiful they were, coupled with that hole that they left when I no longer had them. Those two things, married, is where the album wound up springing from."

As a teenager, several years before she came out as transgender, the decision to reveal to her mother that she liked boys meant immediate ostracization from her Southern Baptist congregation — the close community she grew up in — and from her whole family. This isolating experience doesn’t define Cain, nor has it permanently tainted the love she has for her family, but it casts an undeniable shadow over this album — manifesting clearly in songs like "House In Nebraska" and the album’s breakout single, "American Teenager."

"American Teenager’s" synthy heartland rock (she cites Bruce Springsteen as a longtime source of inspiration) mixes with coming-of-age relatability akin to Taylor Swift’s youthful "Love Story." And while this is by far the closest Cain ever comes to making pure pop music on Preacher’s Daughter, what separates "American Teenager'" from a "Love Story" is both the dreaminess and darkness looming around its edges — a foreshadowing of what’s to come. Just like the stories she tells over Zoom, the characters and places Cain crafts are so vivid you’re instantly transported to the scenes described.

Grew up under yellow light on the street

Putting too much faith in the make believe

And another high school football team

The neighbor's brother came home in a box

But he wanted to go so maybe it was his fault

Another red heart taken by the American dream

Every song on Preacher’s Daughter is caught in a conflicted internal dynamic — a push and pull between the things she wants most and the ways those very same things can be turned against her. Her anger towards the structures of power and control that threaten her basic human rights and safety, juxtaposed with the sense of comfort and tranquility that her small town southern way of life still provides for her. The tension between her desire to be cared for by a man who truly loves her, and the knowledge that every man she meets has the potential to bring either physical or emotional violence with them.

"I can do this, I want this. And then I can't do this, it's too much," Cain says. "It's just that constant [cycle] of like, 'I'm gonna overcome this, I'm gonna get through this,' and then feeling completely crushed under the weight of it."

In the story of Preacher’s Daughter, several of Cain’s deepest fears are personified as the lovers and family members who inflict pain on her protagonist. Her fear of not being good enough represented by Ethel’s mother, her fear of abandonment by Ethel's father. The first relationship represents her fear of being undeserving of romantic love, while the last — a boyfriend who ultimately murders Ethel — standing in for her fear of violence at the hands of men. "I wrote this in mind of these morbidities of life that won't go away, and I just gave them a face to blame," Cain says.

"People are hearing these songs and they're about the darkest years with my family," she says. "And now my family and I are so close. I see them every weekend and we have dinner together and we talk every day. It's so funny because I'm like, 'Oh my God, this is weird that I'm in such a good place in my life and I'm still surrounded by these dark, dark times.'"

Sweatshirt: Worstok, Corset: Oriens, Shorts: Greg Ross

Those childhood wounds, as well as the anxieties she still carries with her, are an essential part of Preacher’s Daughter, but Cain doesn’t want this story to be defined by victimhood, describing the album as "intensely hopeful and bright" despite her character's doomed story arc.

"I am, at this point, begging for cis people to cut the infantilization of trans people where they're like, 'Oh, if you're singing about being sad, you're sad because you're trans,' or every confidence, every feel good moment is like a personal victory for a trans woman, because usually she's miserable," Cain says, before adding, "No, it's not a personal victory that I think I look good today. I just think that I look good today."

Hood and suspenders: Archival Comme des Garçons, Sunglasses: Photographer's own, Necklace: Archival Dior, Skirt: Vintage (c/o Palace Costume)

Rather than continuing to dwell on the trauma of her childhood, Cain is excited to begin telling new stories that grapple with the challenges of her life right now. Her eyes light up when asked about her next album, the second in a planned trilogy that will work backwards to examine three generations of women in Ethel’s family.

"The next record is gonna be different," she says. "It's not about God and religion and angst. It's about sexual repression and going from a sheltered upbringing to an exploration of your own body and sexual expression and being a woman who wants and likes to have sex and feeling neglected by a lover."

Hood and suspenders: Archival Comme des Garçons, Sunglasses: Photographer's own, Necklace: Archival Dior, Skirt: Vintage (c/o Palace Costume)

She continues, "It’s kind of a horny romance: it's seductive, it's anxious, it's unsure of itself. This is a woman who does not think about God, this is a woman who's like, ‘Why doesn't my husband care about me?’ Her daughter's story was very much defeated and hopeful and angry. You know, chomping at the bit to get out. Whereas her mother is more like, ‘I'm trapped in this house [and] I'm also having to play the perfect wife and save face.’ It’s gonna be a grown woman type record."

Cain is a proud Southerner through and through. Even with its gruesome tales, Preacher’s Daughter acts as a love letter to the place she calls home, rather than a doctrine of grievances, and Cain’s fondness for the American South is something that still confounds so many; namely, that any trans person would voluntarily choose to continue living there in 2022. It’s easy to flippantly suggest that marginalized people should "just move somewhere else" as assaults upon their basic human rights and safety escalate, but how is it fair that these people should be the ones forced to uproot their lives, just because of the cruelty and ignorance of others?

Dress: Vintage

When people condemn the entire South as a terrible place, or even in good faith suggest that these people should flee for their own safety, they completely miss the point that there are countless queer and trans people in these places who deserve to be able to live there freely if they so choose. That’s one of the things that makes Preacher’s Daughter so powerful: no amount of hardship, nor traumatic memories, can break the bond she has to the place she is from. You can hear it the way she sings the line, "I still call home, that house in Nebraska."

Cain immediately recalls an instance when she tweeted about being excited to move to Alabama with her sister, and a stranger replied to her, "I automatically don't trust anyone who says they're excited to move to Alabama." She refutes the idea that the South is some uniformly evil and hostile place for anyone trans or queer, and points out that all instances when she has been verbally abused and harassed on the street have happened while visiting places like Los Angeles and New York City.

Dress: Vintage

Dress: Vintage

"I had my issues when I came out in high school, it was rough, but as an adult now — [and] the knowledge that I am, you know, in cis terms 'passing' is not wasted on me — even the people who know that I'm trans in public... they don't care,” Cain says, also arguing, "Contrary to popular belief, people are respectful down here. People are all about boundaries and not disrupting an environment. The South is very still, very quiet. People are very friendly, very kind to each other in public. There's a warmth here that people don't really get to understand unless they come here."

That outlook is felt throughout Preacher’s Daughter, an album that somehow emanates a heavenly glow despite taking you on a tour through many of Hayden’s worst-case-scenario nightmares and insecurities. As she puts it, "For anyone who lives a life where the usual pitfalls happen on top of having a marginalized identity, you get to know a lot of morbidities, a lot of darkness, and that's something that you can't escape."

Crown, veil and gloves: Vintage

Crown, veil and gloves: Vintage

She continues, "I could sit here and pretend like things are all hunky-dory all day long, but the fact of the matter is trans people are being killed and abused and hurt just for being themselves. These are uncomfortable, unfortunate realities that I could pretend don't exist and you could pretend don't exist. These are things that will hang over our heads, so I find it is easier for me to confront these things head on and be like, 'This is a reality; this is something that is true, and it happens.' I am still going to be optimistic despite this, because sometimes my hope and my optimism is all that I have."

Cain’s hope and optimism are best represented by the album’s last two tracks, which ironically take place after the character of Ethel has died. On "Strangers," Ethel’s mother sees her daughter’s picture on the side of a milk carton — Ethel’s cold, chopped up body already sitting in her cannibal boyfriend’s freezer — and though it’s a viscerally grotesque concept, the imagery is soothed by the album’s incredibly tender final lyrics:

Phoned you just to tell you that I made it real far

And that I never blamed you for loving me the way you did

While we were torn apart

I would still wait with you there

Don't think about it too hard

You'll never sleep a wink at night again

Don't worry 'bout me and these green eyes

Mama, just know that I love you

And I'll see you when you get here

For the character of Ethel, this is an undeniably tragic ending: singing to her mother from heaven, forgiving her even though it’s too late to be saved. But for Hayden, the young woman who is only just beginning her journey, it represents a beautiful reconciliation of mother and daughter, despite the hard times between them in their past.

Crown, veil and gloves: Vintage

"In 'Sun Bleached Flies' and ‘Strangers,’ that is the hope that I carry on every day to remember," Cain says. "Though things are bad and they get really dark sometimes, the sun will always rise tomorrow, and if I'm still breathing, there will be another day. That's what I have to hold on to, and that's what this whole record was for me. It was a direct confrontation of all these things I'm scared of and being like at the end of the day, all this is true. Keep going."

Photography: Moni Haworth

Styling: Joanie Del Santo

Hair: Rob Talty

Makeup: Nick Lennon

First styling assistant: Annie Lavie

Second styling assistant: Raea Palmieri

Retouching: Matty So

Video editor: Caroline Fortuna