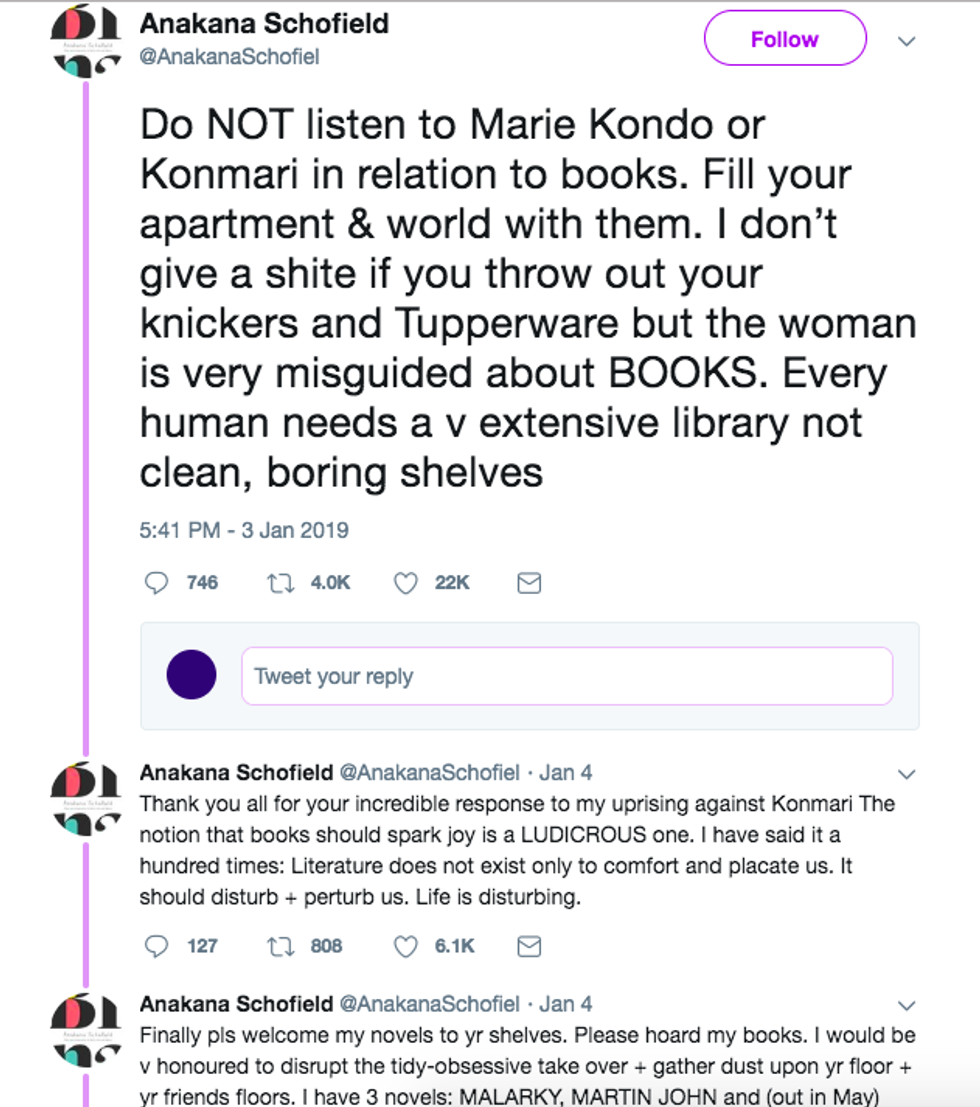

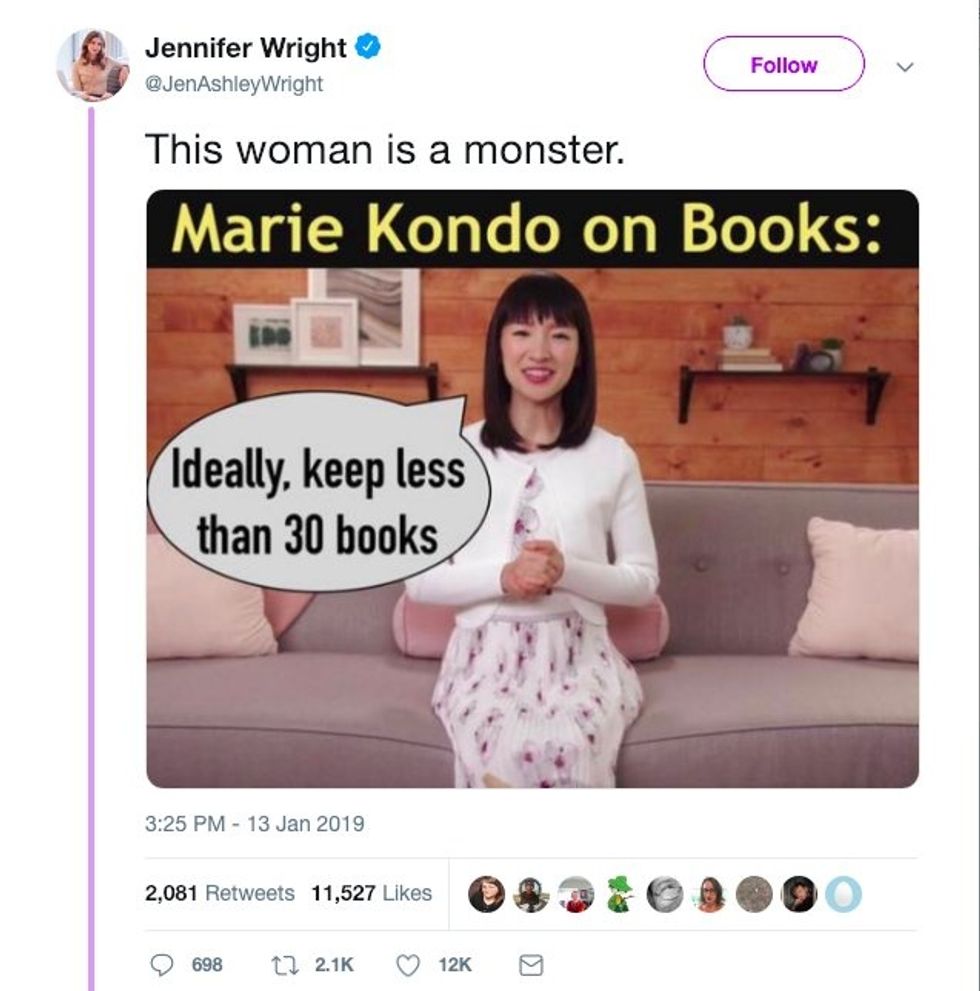

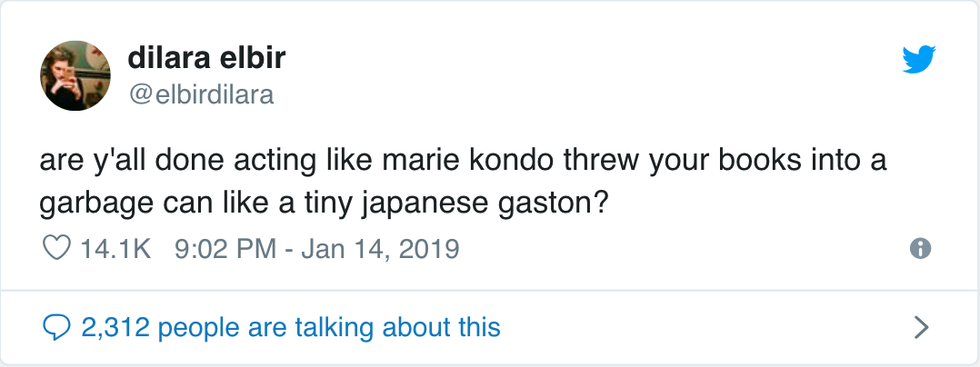

Marie Kondo became famous for her 2011 book The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up and has recently become a viral internet phenomenon with the release of her Netflix series Tidying Up with Marie Kondo earlier this month. Although her show was initially met with positive reaction and internet virality, the white public has suddenly turned against her. An avalanche of attack pieces, tweets, and comments largely by white people has been launched at Kondo. This backlash was initially triggered by statements that Kondo made regarding books in episode five of her show. In numerous viral tweets and pieces, white people alleged that Kondo was forcing people to keep under thirty books, telling everyone to throw out all of their books, and was a threat to literature. A viral tweet by a white woman, Jennifer Wright, who later apologized in response to criticism, called Marie Kondo a "monster" and photoshopped a speech bubble onto an image of Kondo stating that she was telling people to keep under thirty books.

These accusations have now been proved to be lies and a willful misrepresentation of Kondo, who has stated repeatedly in her book and on her Netflix show — that she personally keeps under thirty books but that others should keep as many as is fitting according to how much they value books. Interestingly, even her statements in episode five that triggered this white rage are surprisingly tame and provide no basis for the attacks. In the episode, she gently advised a frazzled couple regarding books, "Take every single book into your hands and see if it sparks joy for you. Books are the reflection of your thoughts and values."

In addition to the book controversy came a wave of outraged pieces by white people mockingly fixating on Kondo's "spark joy" phrase and jeering at her philosophy as "moral righteousness." Anakana Schofield, another white woman, whose viral tweets started the book controversy, used coded racist language —"fairy finger" "woo-woo nonsense"— to disparagingly refer to Kondo's Shintoism-influenced methodology in her piece in The Guardian. Then came further endless tirades by, you guessed it, more white people eviscerating Kondo's method for not working perfectly for their hyper-specific personal situations, projecting extreme malice onto Kondo, and launching patronizing vitriolic attacks such as, "[T]ake your tidy, magic hands off my piles."

In nearly every major publication, white people have repeatedly grabbed at the mic and been given the platform to attack and be the authority on Kondo, a Japanese woman and woman of color. Ultimately, white people's initially voracious viral consumption of and then sudden vilification of Kondo exemplifies the duality of the tropes projected onto Asian women — we are either a fetishized exotic experience or embodiment of a yellow peril threat. Once Kondo was no longer an exoticism's site of pleasure and exploitation for white people to experience their orientalist fantasies, she became the other orientalist trope — the yellow peril threat to white people's insecurity over their destructive capitalist consumption.

In contrast to the enormous wave of criticism by white people portraying her as a frigid mystical dragon lady, Kondo in both her show and her book has repeatedly emphasized that the core of her philosophy is a gentle approach based on one's individual sense of value for items. In her show, Kondo is a kind guide, helping the guests tidy their homes while repeatedly stating that her philosophy is a non-forceful and gentle approach centered around the person.

In fact, as Twitter user Clara Mae pointed out, Kondo in her book explicitly prescribes against tidying methods that enumerate a specific number of items to keep. She wrote in her book, "The majority of methods give clearly defined numerical goals...but I believe this is one reason these methods result in rebound...Only you can know what kind of environment makes you feel happy."

If any of these white people read her book or watched her show even briefly, they would have realized this. Or perhaps they did, but the truth did not fit into the ominous orientalist narrative about Kondo that they seem determined to construct. Ultimately, Kondo was forced to come out with a statement, reiterating yet again that her philosophy is explicitly against the harsh, forceful approach that white people have projected upon her. She stated:

"I do think there is a misunderstanding of the process, that I'm recommending that we throw away books in the trash or burn them or something… The most important part of this process of tidying is to always think about what you have and about the discovery of your sense of value, what you value that is important. So it's not so much what I personally think about books. The question you should be asking is what do you think about books."

The contrast is startling between the gentle philosophy she espouses and the perception that white audiences have, against all reason, projected onto her as a bogeyman from the Orient descending upon the peaceful West to throw away their books and possessions. In actuality, the backlash has little to do with Kondo — who has done nothing wrong — but instead entirely to do with the duality of orientalist tropes projected by whiteness upon Asian women. To whiteness, our bodies are either exploited by whiteness as fetishized experiences or the embodiment of a yellow peril threat.

The internet provides a digital conduit for the white gaze to virally and endlessly consume bodies of the "Other." To the white Western audience that consumes Kondo via their screens, Kondo fits the white West's fetishized conception of the ornamental yellow Asian woman. As Professor Melissa Borja wrote, Kondo's virality and traction with white audiences may in part be due to the fact that her image and show fits the white conception of the oriental "sage" coming to deliver a mystical message. The white West is fixated on the exotic Orient as a resource to extract from, and Kondo comes onto our screens as a non-threatening means through which white people can consume spiritual Asian religions in a palatable and neat manner.

Kondo is a vector through which white people can consume "Asian-ness" to assuage their insecurities about their destructive capitalist consumption and economic anxieties over the U.S.'s potentially faltering power as an imperialist superpower. Kondo may even provide a palatable East Asian foil to the white West's racist, orientalist fear of China as the yellow peril superpower coming to take away the U.S.'s wealth, which it accumulated via racist and global imperialist exploitation.

Thus, Kondo's show first achieved enormous virality likely in part because whiteness deemed her worthy of consumption to alleviate their own first world white capitalist anxieties. They were able to project their orientalist conceptions of the exotic Orient onto her and derive their fantasies of "Asianness" for their own pleasure. However, the sudden backlash against Kondo exemplifies the violence with which whiteness consumes Asian women's bodies and non-white bodies in general.

The white West's consumption of images of Asian women via the internet and digital representations almost always reduces women to certain fetishized tropes, meant solely to be exploited for white pleasure. Our images are never fully ours. Instead, our bodies and images are snatched by white audiences, viciously warped, and ultimately used against us. Our value and utility only last as long as whiteness chooses to consume and forcefully derive pleasure out of us. At the hint of deviation from whiteness' authority, our existence and images are suddenly no longer of use — and whiteness turns hostile and attacks.

Whiteness' ego is fragile and fickle. Thus, at the drop of a hat and the most benign of statements, white people turned on Kondo. Once Kondo was no longer a useful fetishized salve to the white West's anxieties about their capitalist consumption for them, she became the other orientalist yellow peril trope — reminding white people of their own stress surrounding their first world economic anxieties and destructive capitalist consumption. White people suddenly became enraged at their perception that an East Asian woman had the audacity to tell them what to do. She has now been relentlessly attacked by a barrage of self-righteous white people.

Major publications have published an avalanche of think pieces with coded racist language, such calling her philosophy "fairy finger motions" "woo-woo nonsense," repeatedly referring to her "diminutive" stature in relation to her being a Japanese woman, and patronizingly referring to her method influenced by Shintoism as fake "magic."Her image has been distorted over and over by white people to create a wave of (often demeaning) memes. Her rich and kind philosophy has been reduced to a reductive "spark joy" catchphrase that white people have latched onto to make infantilizing memes and pithy jokes about. Her image has been manipulated and commodified by companies to capitalize off of whiteness' viral consumption of her.

Thus, what has happened to Kondo — the en-mass viral consumption and then sudden disposal of her, all via the internet — evinces greater truths about the duality of the exploitation of Asian women and about whiteness' exploitation of non-white people as a digital voyeuristic experience of the "Other." To whiteness, the existence of non-white people is only valuable as long as whiteness deems our existence pleasurable for their consumption. To white people, Asian women's bodies are either fetishized sites of exploitation to mine and extract for their own pleasure, or the embodiment of the threatening yellow peril orientalist trope. They voraciously consume our bodies, images, and cultures to satisfy their orientalist fantasies. But once white people deem we are no longer of value to them, they do what they always do to Asian women and non-white people in general — they attack and tear down.

Photo via Instagram