Much has been written about the young photographer and artist John Edmonds, and his approach to toxic notions of racial bias and the role it plays in how we as a society tend to view blackness.

But nothing captures Edmonds' true intent like seeing the art up close and personal. It's even better when given the opportunity to speak with the D.C.-raised, New York-based artist about his work and his intrinsic motivations. When going to meet him at ltd's whitebox Lower East Side gallery space (he is repped by ltd's Los Angeles headquarters) currently showing Edmonds' latest solo work, "Tribe: Act One," I was struck by what the author and feminist scholar bell hooks wrote about Black art and visual politics in 1995's Art on My Mind, specifically what she had to say about the role of the camera and photography through the Black lens.

One passage in particular is with me as I head down Orchard Street. hooks writes about the place of art in Black life, the "connections between the social construction of black identity, the impact of race and class, and the presence in black life of an inarticulate but ever-present visual aesthetic governing our relationship to images, to the process of image making." And hooks has more to say about this business of "image-making," a term Edmonds uses in our conversation moments later when referring to his own work: "The camera became in black life a political instrument, a way to resist misrepresentations well as a means by which alternative images could be produced."

bell hooks, as usual, is totally correct. Edmonds, who holds a MFA in photography at Yale's School of Art, presented a series called "Hoods" in 2016, and last year, another untitled series featuring do-rags. Both series depicted people who were presumably Black men (their identities cleverly and strikingly obscured by hoods and do-rags, and the fact that backs of their heads were thus not visible). As such, they stood in as literal figureheads for discussions around toxic masculinity, racial bias, and what we think about when we talk about blackness in society, especially in light of movements such as Black Lives Matter and debates around police brutality, who gets criminalized, and who gets a pass (no one Black gets a pass). In other words, to paraphrase an old adage, there is always more present with Black art than meets the eye.

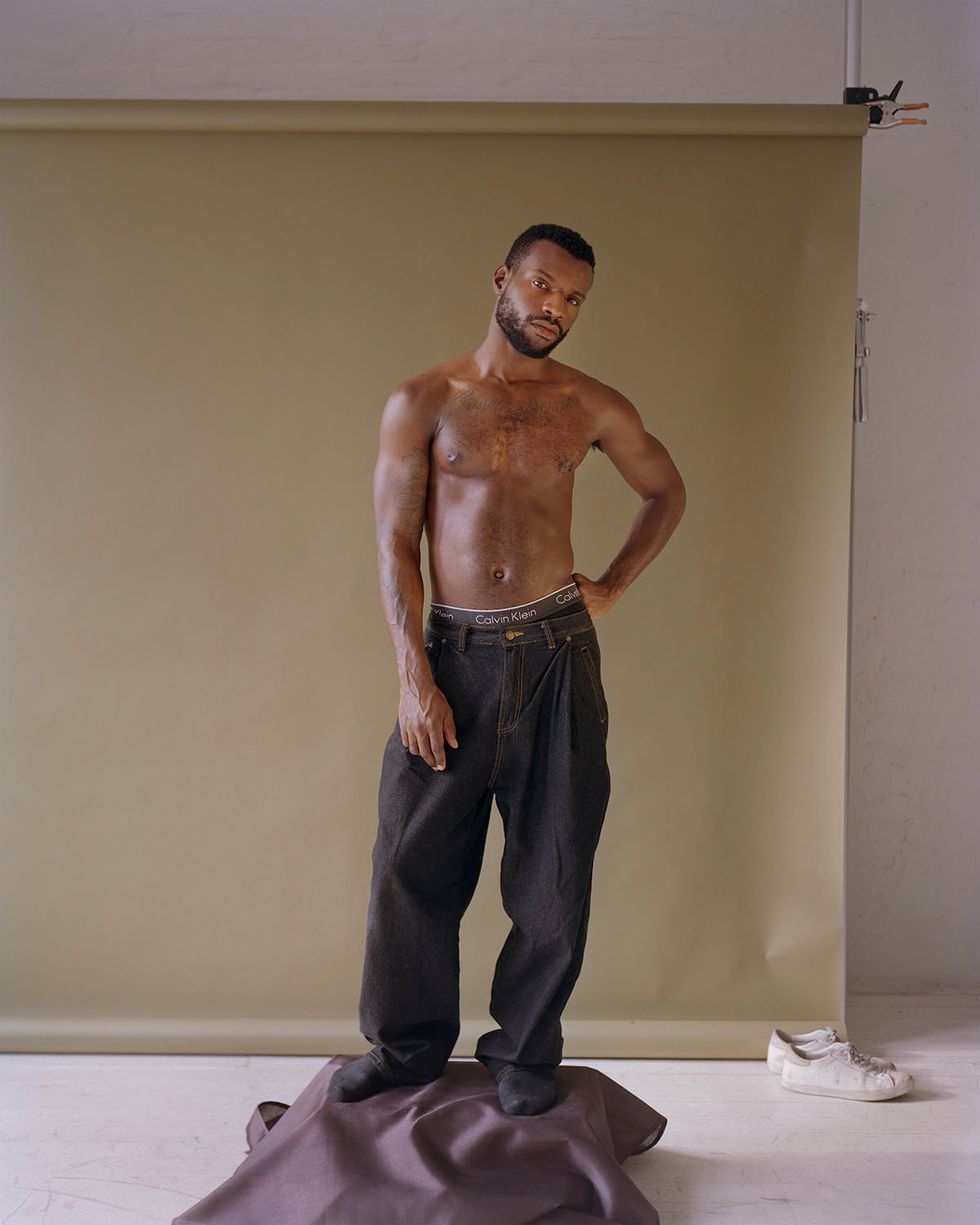

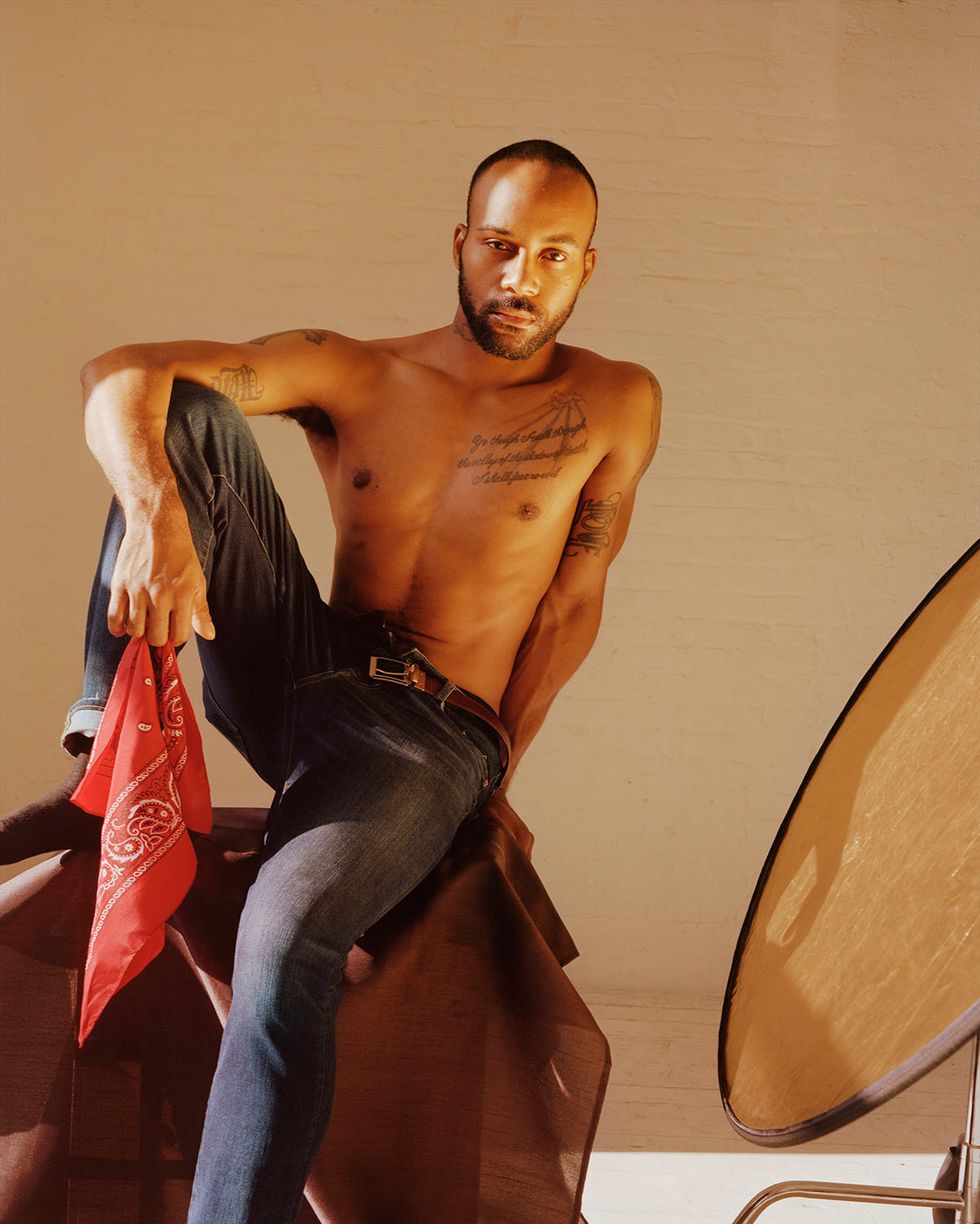

Having only seen those works as a Black queer person, and having not met Edmonds, a Black queer person, I only had my experiences to go on. I thought that my own bias made me less privy to misrepresentation of Edmonds' work, and I was pleasantly surprised to learn I was wrong. Rather than focusing on Black masculinity, and whether or not it is problematic, Black beauty actually plays a much more important role in Edmonds' work, as I saw up close when I met him at ltd to discuss "Tribe." He collaborates mostly with queer artists, some are nonbinary, and all represent facets of blackness not often captured on camera. Ihab, Khari, Ladin, Milton, Brittany, Alex, Tom, Victor, and Justin comprise a range of identities and experiences with a story to tell in each photo. Their aesthetic versatility, framed by Edmonds' use of glowing natural light and warmth invite the viewer to experience an almost feminine softness.

One of the works in "Tribe," Face As Mask II, Brittany is shown cradling her face, accented by dyed-blonde waves, created by Black hairstylist (and former Edmonds muse) Malcolm Cuthbert. In the portrait, Brittany's face seems almost detached from the body. "There is fluidity always, to how the body can be used," Edmonds says. "And to me, the waves in her hair give the photo overall a mermaid-like, aqueous quality. It's a deeply subjective thing, but it's how I see it."

For Edmonds, a Cancer who turns 30 this summer, the stars might say emotional availability and nuance flows through him effortlessly and translates to the art he creates. I say that I'm more than happy to be proven wrong, but "Tribe" is essentially a meditative series about the communities and families we create, and the beauty we are all capable of accessing through silence. In a world that is so loud and often traumatizing, Edmonds' quiet beauty cuts through the noise. Read on.

What do you make of people who say your work is primarily about Black masculinity? That was one of my own personal reads of your work when I first encountered it.

In the past people said it's about Black masculinity which is interesting because for me I found my work to be very feminine aesthetically. For me despite having photographed subjects who identify as Black and male, I feel gender, as a queer person, the way we see it is so limited. A lot of my work, I think about it as a space to undo limitations and biases people have attached to whether it is someone who identifies as male or reads that way, so in a lot of ways, this show is the first show where there are people who very much identify across the spectrum. A lot of that ties into me creating this fictitious tribe.

In your mind, how is "Tribe" different from past works like "Hoods" or your do-rag series?

With many of my pictures, and with photography in general, it gives you the surface of something or someone. For me, it's been good at starting there, then going beyond the facade. Many of the people in my shows and in this one, are people within creative communities. You wouldn't be able to tell that just from first impression. In this show, and in past works, people often address the work in a way where they talk about these figures as Black males, but it's interesting because you can't exactly see or tell that. The viewer's gaze is interesting because in some ways, different gazes complicate a narrative, but in a good way that adds to a larger discussion of whatever it is I'm hoping to address. It just goes to show that we all come to view a work with our own biases and the ways in which we see the world. With this show, I'm hoping to hold myself to continuing to subverting expectations. In this medium, I'm always thinking about ways to do that.

How does the use of light play into what we're seeing here?

All the photographs in the show are made with natural light. I'm using this big gold reflector. With the way that Black figures appear in art, if it's not a Black artist framing it, it's often shown to the bourgeoisie and depictions of Black bodies are different by upper-class white people. So the way the skin is shown in my photos, is I like to show the warmth and the tones of the skin, because they have such beautiful qualities when illuminated properly.

On my way here, I was thinking about what bell hooks wrote about the need for more Black writers critiquing Black art in Art on My Mind. I'm a Black writer and we're talking about Black experiences, but what's something about this project that anyone else whose looking at this could gain, not having the perspective maybe you or I might have?

I'm really interested in the emotion of art. It's essential, and I think about how space within this exhibition, parses out emotionality. On one side of it, I have photographs that represent a type of submission and softness, and the opposite shows power and direct connection with viewer based on the gaze. The gaze in a lot of my work is about looking and being looked at. I collaborated with Malcolm Cuthbert, who is a hairstylist based here. He has been working on this project and was my muse for my do-rag images. A lot of my work is predicated on real-life experiences. So in a lot of ways, the people who are participants become collaborators. I always photograph actual models and I like to think that in the process of scouting people, one of the reasons it's called "Tribe," is because I'm building one.

I remember the trending hashtag #softmasc, which subverts the gay trope of a harder, "straight-acting" #masc4masc masculinity. How does your work in "Tribe" reflect that idea?

In general, I always aim for a softer, more tender portrayal of masculine and feminine figures. It has a lot to do with me wanting viewers to see a subject's beauty. In "The Villain," featuring Tom, despite them wearing clothing that might be symbolically charged, the eyes are filled with emotion and softness.

It seems that even the dominance in some images feels softer.

To me, this exhibition allowed me to think about several types of image-making, too. There are several types of portraiture I'm working with. There are pieces with hair extractions and still-life portraits. In previous works, like with the do-rag series, I'm working with a consistent form. I'm working with repetition, and that is to show the nuance of difference. For me, nuance and subtlety have been important parts of my work. That allows for a viewer to enter the work and have a real human experience with it.

Was there a moment in your life that struck you and helped you decide to create this particular body of work?

A very definitive moment for me in art-making in general was when I was in undergrad, and I was getting my BFA in fine art photography [at Washington DC's Corcoran School of the Arts and Design]. For me, I'm interested in blurred lines. Photography is a moving currency. When I was studying there, I saw the 30 Americans show from the Rubells' Family Collection. It was my first time seeing Black contemporary art. That for me was extremely liberating. We're at this point now where all these nuances of the Black experience are being unveiled, and that's obviously a great thing. But within art history and pop culture at large, there had been up until recently a monolithic portrayal of blackness. When I was the 30 Americans show, I saw the ways in which these Black artists talked about race and gender; about public and private, and how we come to frame history. A lot of the pictures in my show deal with history. I'm using these African decorative masks that are not specific to a tribe in Africa but are repurposed. One of my favorite pictures is of Alex, "His Strength." He's Haitian Creole. When you think of Haitian people and their physical features, Alex doesn't look like how you might "expect" him to look as a Haitian person. For me, the show poses these questions as to what makes something real or authentic. Also, the work, despite being politicized, it's always really appealed to queer people specifically because we know what it's like to have our authenticity questioned.

Related | The Enduring Influence of Lorna Simpson

That brings me back to what I thought earlier — about the ways in which you were depicting Black masculinity. It turns out I was wrong. It helps support what you just said about queer people needing to validate their perspectives.

I appreciate you saying that! It's okay to see things through your eyes, too. When you have post-modern image-making examples set by people like Lorna Simpson and Carrie Mae Weems and others navigating the ideology of the gaze, in a lot of ways, people don't simply look at the artist and say "this is what it's about." We're able to unpack our own expectations about who or what someone or something is.

When it comes to carving out space, creating your own tribe, do you feel a certain calling to always do that in your work? People need to see and be seen for who they are.

In terms of visibility, we're in this point in time where there's a lot more individual perspectives that are being made visible. There's more of a desire of these things to be seen as such. I use the power of silence. There's a quiet power to that.

Silence seems to be a lost art.

I love this picture of Ihab ["Modernity"] so much because when you think about the stoic nature of their expression, it's almost loud. When I was younger, I remember being at home in the middle of the day on a Saturday in Washington DC, and how I could hear silence. I like thinking about understatement as a way to seduce the viewer. We are in a moment where so much is trying to grab our attention, and it creates a tunnel of anxiety for people. For me, silence is more invitational, and there's power in introspection and contemplation. I started meditation earlier this year.

Meditation is a game-changer.

I use the Calm app. It's been very important for me, in creating a sense of mindfulness.

There does seem to be a quiet power constantly at work in this show, based on the mindfulness you're talking about.

Thank you for saying that! As a Black artist specifically, I've been thinking about ways to not make the work reactionary. It has nothing to do with the exterior world. The idea of being responsive and not reactionary to the ubiquity of information and images bombarding us. It's important to find your quiet, find your peace, and then, without fear, say what it is you need to say.

John Edmonds' "Tribe: Act One" is on view through May 31 at ltd Lower East Side. Follow Edmonds on Instagram.

From Your Site Articles