Art

A Puerto Rican Teen Is the Subject of This Artist's New Exhibition

by Jhoni Jackson

31 October 2018

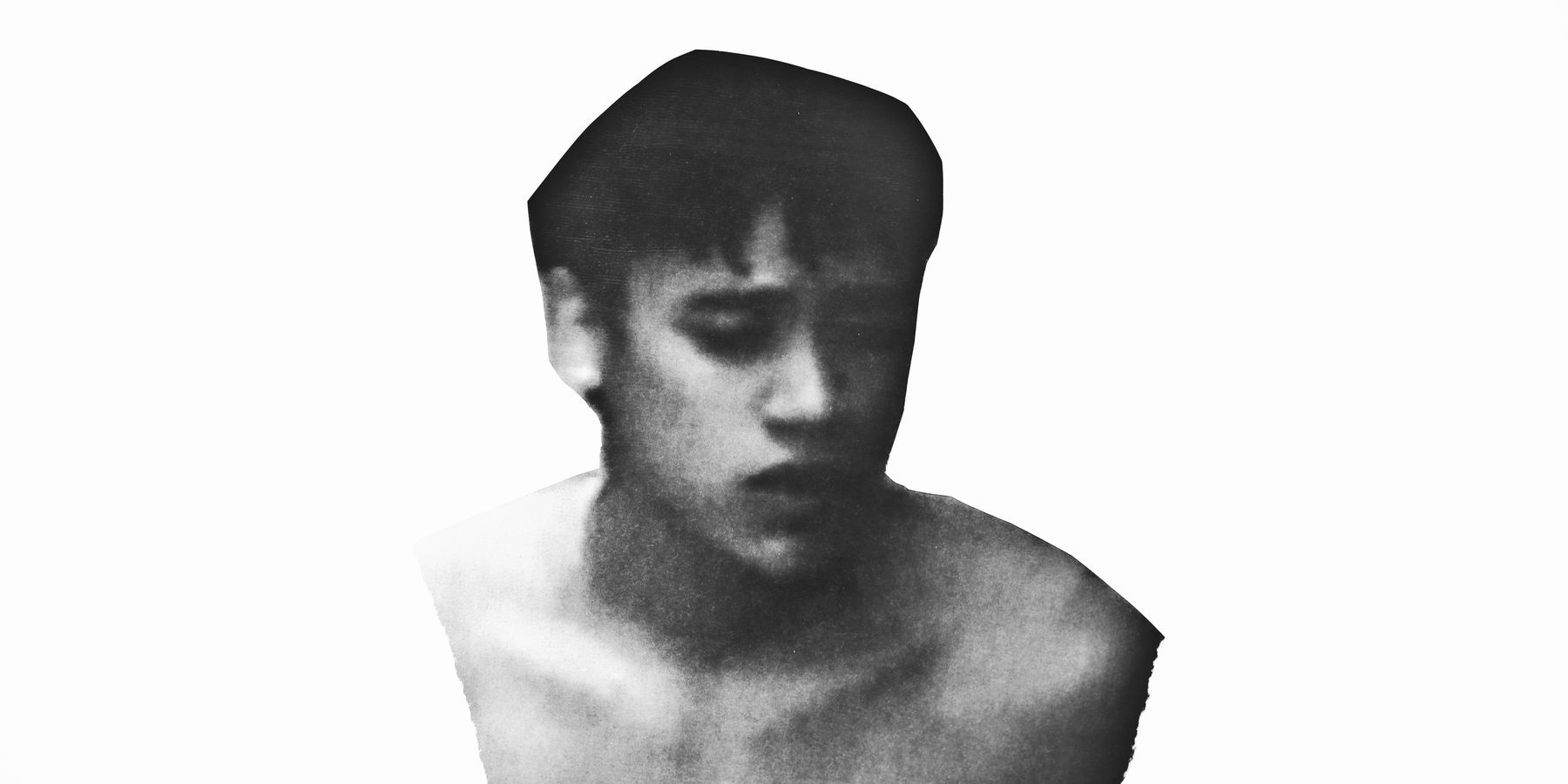

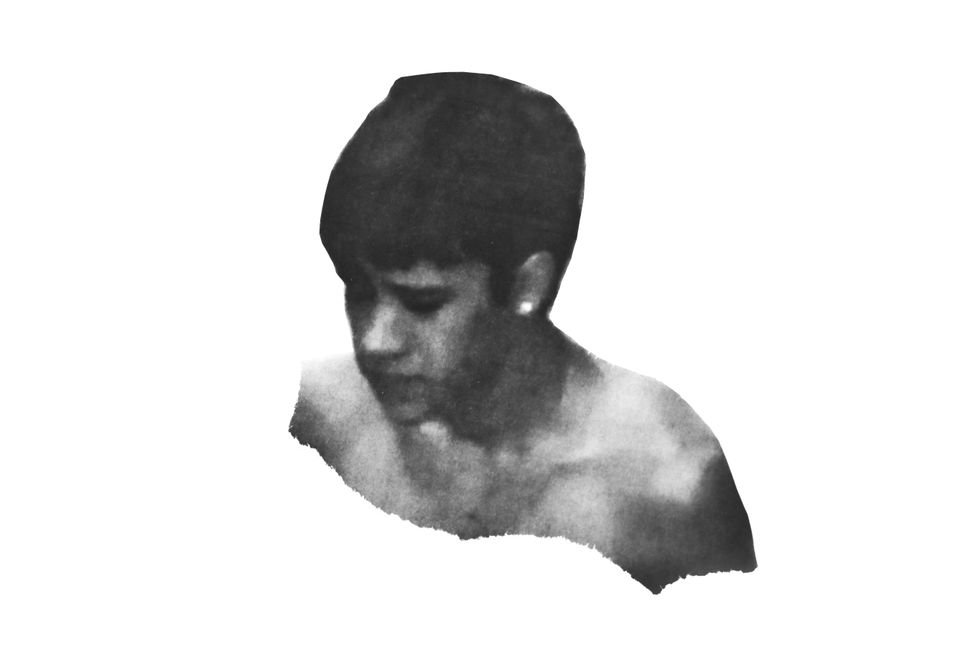

The subject of French artist Camille Rouzaud's first-ever solo New York exhibit, Raúl, is a Puerto Rican teenager she met a few years ago, back when she lived in the island's historic neighborhood of Old San Juan. Drawn to studying performativity and the complexities of living, she spotted Raúl in casual conversation from her balcony, and started filming. "He had this very beautiful and free energy of movement that I seek out so much," she says. That documentation sparked a friendship, and the footage became a well from which to continue investigating.

For Puerto Rican-born Natalia Viera Salgado, who curated Raúl, Rouzaud's exhibit illuminates "all the layers we go through when we are growing up: failures, experiences." Resilience and resistance figure greatly in Rouzaud's artistic efforts; as means of self-preservation, they're human nature, and her work often explores those instincts through the impetuousness of adolescence. "The subjects in her work fear nothing," Viera Salgado adds. "Yet they also show emotion, and I think it is a beautiful thing to notice."

Still, Raúl should be considered in context: The subject lives in Puerto Rico, a U.S. colony where the debt crisis has led its government, working in part at the behest of a federally-appointed Financial Oversight and Management Board, to close nearly 250 public schools last summer. And the outlook from there isn't so bright, either: Budget cuts and tuition hikes at the University of Puerto Rico will undoubtedly limit access to secondary education (some students are already struggling to stay enrolled, with more cuts are on the way), and the island's average annual income is less than $12,000. Right now, more than 40 percent of Puerto Ricans live below the poverty line.

"Growing up in an island like Puerto Rico is very tough, especially in our time," Viera Salgado says. "And I don't say it in terms of the street, but to see how the system is dismantling our education system is very frustrating. I feel these kids learn to survive and navigate many things that their parents experienced very differently."

Rouzaud doesn't purport to speak for Puerto Ricans, but her own experience — a queer woman who grew up in French public housing — certainly informs her understanding of inherited oppression. Read our conversation, below, to learn more about Raúl, and how Rouzaud's connection to Puerto Rico and her own identity intersect.

I know you were born in France and currently live in New York City, but can you give us some insight on how you developed your voice as an artist?

My own complexity, my own acceptance of who I am. I fought myself so much and felt so defeated during my teenage-hood. But I remembered the unconscious strength that I had sometimes as a kid. I look for that. I'm looking to be this wild animal again. But I grew up and I can't really be this fearless kid again, so I put it in my work. It's a form a therapy for me. Sometimes the kid in me can be very afraid so I try to find comfort and gain invulnerability through my work.

What brought you to Puerto Rico? How long were you living in San Juan?

First time I traveled to the country was 10 years ago 'cause my girlfriend at the time was from there. Back then I was living in Barcelona and hanging out with the Puerto Rican community there. With time, I grew family and friends for all those years and their culture become part of my culture. Now it's equally as present as my Mediterranean culture, maybe even more. I've spent the last 10 years going back and forth, but I was living there between 2013 and 2015.

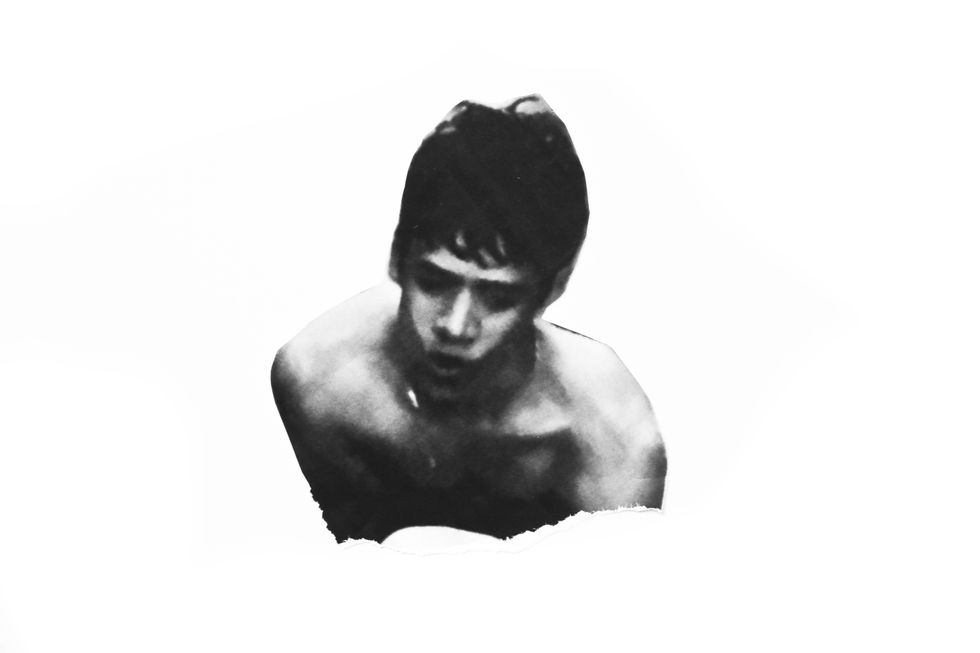

How did your friendship with Raúl begin? What prompted you to film him back in 2015?

Raúl was my neighbor in Viejo San Juan. I was living just in front of his building. One day he was having a conversation in the street, I was on the opposite balcony and I just started to film him. He had this very beautiful and free energy of movement that I seek out so much. We met down to the street the next day and I showed him some of the images I took out of the footage and he was like, "Yeah, that's cool, we can even film more?" And so we became friends.

In your artist statement, you noted a fascination with the "capacity for resistance" of teenagers. How does Raúl exemplify this?

It's about the movement, having this power in your body, like a wild animal, feeling invulnerable. In those videos Raúl is very much like that.

Considering the chronology of Puerto Rico since your 2015 documentation (including the crisis post-Maria), has the significance of this project changed since its initial creation?

Yes it changed, but mostly for personal history, not out of a political reason.

I suffer for Puerto Rico's situation. I fully support the idea of independence; Puerto Rico is a very solid inspiration in my work but I feel like it's not my place to be political about PR in my work. At least not deliberately. I'm just proud to be linked to the island.

My influences are more global: It's not just the oppression of the people of Puerto Rico specifically, it's the difficulty of being from a place where you feel like you're not accepted or are considered a second-class citizen. Like the public housing where I grew up in, for example, with poor people from everywhere, fighting for the right to be treated the same as all other French citizens. Or growing up gay in a hostile environment.

The capacity of resilience.

Can you tell us more about what the original documentation was like? What did Raúl think about it?

The original footage is a conversation in the street between three teenagers. Sometimes intense, sometimes silent, some moments of affection and games. Actually some of the original untouched divided footage was published in Collection of Documentaries, an English magazine, in 2016.

But I wasn't quite satisfied with the untouched footage. I knew I could get more out of it, something deeper, something even more close to me.

I kept Raúl informed about the evolution of the visuals and he seemed happy with it. Actually, I sent him the photos of the exhibition a few days ago and he said "se ve cabron." (Roughly translates to "that looks awesome.") So I think we're good.

I love this group of work so much that some of his images will actually be traveling to Hong Kong for the Design and Art fair early next year.

How did you choose the stills to incorporate into this exhibition? What significance do the materials used for sculpture have?

If they vibrate within me, I go with those. It's also easier when it's the same person throughout the work because that person can't betray his own expression. As far as the materials, stones, heavy plexiglass, concrete... these just reinforce the purpose of my work. Strong, indestructible materials.

Looking to the larger Youthquake prompt and its aim to spark a dialogue about "collective consciousness and understanding how semantics can play a crucial role in shaping public opinion," where does Raúl fit in?

He is both a fragile and invincible being, as we all are — on the edge of chasm. And the madness of youth makes it even more apparent. So hopefully it's a universal dialogue.

Photos courtesy of Camille Rouzaud / Hunter East Harlem Gallery