Art

Talking Representation, Masculinity and Emotional Expression With the Creators of "Black Boy Feelings"

by Michael Love Michael

18 July 2017

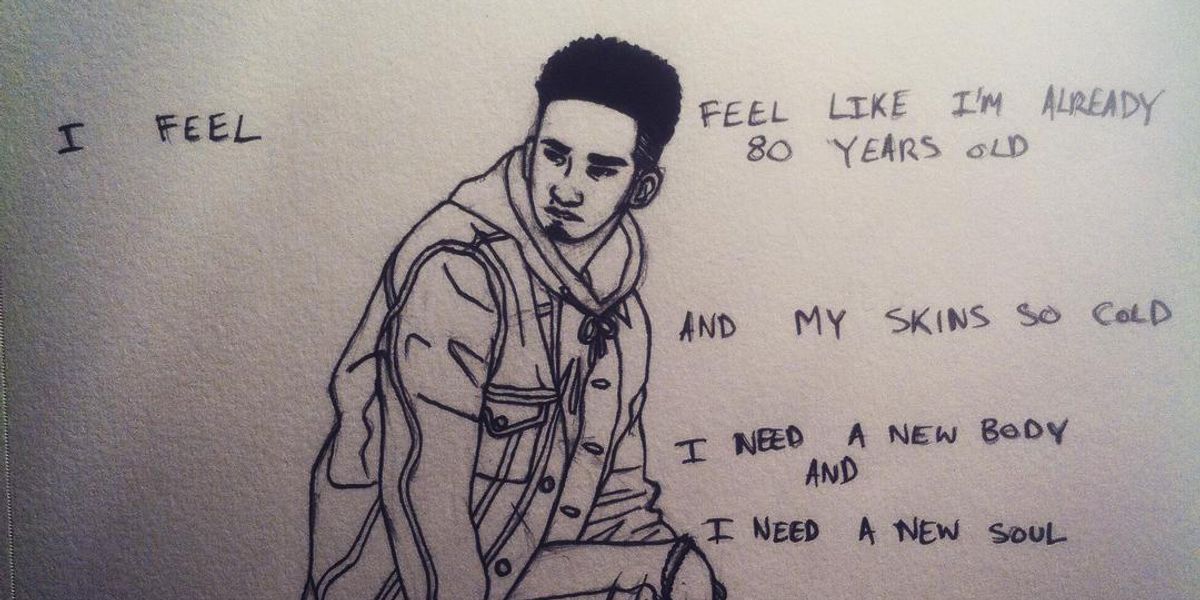

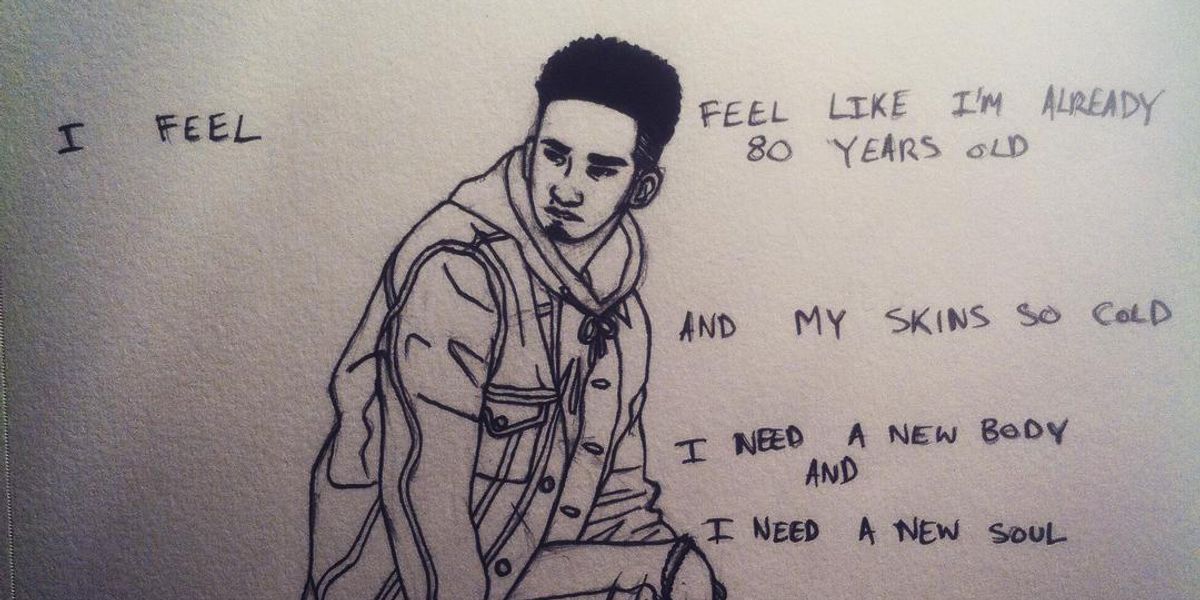

Courtesy of Black Boy Feelings

I first met 23-year-old artist and wunderkind Richard Bryan at Vanessa's Dumplings in the East Village about a month ago. Fresh out of college (he went to Colgate in upstate New York, a place that he calls "cold and white as shit"), native Brooklynite Bryan is co-editor of the new book Black Boy Feelings, Volume 1: Boyhood, alongside his creative partner, 22-year-old Jeana Lindo. As you'll learn, the book is several things, but it is a self-described "anthology about black masculinity."

I can identify. As a 20-something black queerling who is often told that my emotional intelligence and vulnerability are forms of violence to white supremacist patriarchy, it was both eminently cool and validating to meet someone like Bryan -- someone I could see myself in.

Through this book, he and Lindo are explicitly trying to create a safe space for the all-too-often overlooked interior lives of black males. In other words, Vol. 1 gives access to a perspective we don't often see in mainstream culture. More impressive is the fact that Bryan and Lindo curated, edited, produced and published the book independently. In its scope, Vol. 1 is an ultrachic, magazine-style, 218-page work culled from hundreds of artists' nationwide submissions ranging from poems and short-stories to striking photographs and graphics.

In a time where it needs to be voiced that Black Lives Matter, and poignant storytelling about the emotional lives of unforgettable black characters gains traction, (perhaps illustrated most powerfully and recently in last year's devastating Oscar-winning turn by Mahershala Ali in Barry Jenkins' Moonlight) now is as good a time as any for people everywhere to get all up in the feelings of black boys 'round the world.

Over teriyaki dumplings, Bryan and I chatted awhile before getting Lindo on speakerphone, who was vacationing in her native Florida, and together, we discussed their serendipitous union, the making of Black Boy Feelings, Vol. 1, the diversity of black males, the Black Lives Matter movement, and future plans for world domination.

Jeana Lindo and Richard Bryan; Photos courtesy of Black Boy Feelings

In the introduction for the book, you write that the world is largely unconcerned with what a black man has to say unless it's accompanied by snares and 808s, which is true. What made you want to open the book with this statement?

Richard Bryan: My message for black men like me is that what's on your heart is valid. Not just the entertainment shit is valid. And people are very quick to listen to a mixtape and some beats, and that's real as a legitimate form of black expression, but that's not the only avenue we have to voice our emotions. It is the one most commonly accepted by white people. And to be real with you, I often feel that the only reason why people give a shit about what I have to say is because I come from a place of some privilege. I went to good schools and I'm smarter than the average bear, which gives me maybe more access to certain channels through which I can and am allowed to express myself. But let's not get it twisted: I'm still very much treated like a black man in American society, regardless of where I come from or where I went to school.

Tell me more.

Bryan: A small example, but you know, I was recently arrested for an unpaid bike ticket, but the way the whole thing went down was very typically unnecessary. I was riding my bike on the sidewalk and was ticketed one day. OK, it's whatever. But one night I'm in a park when it's dark and some police roll up and stop me. It's crazy that I knew not to try and run away because that would make things worse. Plus, I didn't actually commit a crime. So they run my shit and are like, "you've got a warrant out for your arrest from this unpaid ticket." So they lock me up at the precinct for five hours, then take me to Central Booking for 22 hours. And It's like... I had shit to do, man.

Back to the book, which obviously comes at a time where people are being made more aware on a very public level about the value of black lives and voices. How important was it for your to capture a diverse range of voices?

Bryan: Though there's a lot of stuff that's fucked up right now, creating this book with Jeana was a partially a thing of access for black men to express themselves and a thing of fear. I don't like talking mostly and it's because most people don't like to listen. But of course, I do recognize that it is very necessary. You can't bottle everything up. And of course, we are not a monolithic people. There are shades of that all throughout the book. The Jamaican experience is very different from the black American experience, for example, even if we live in a society that tends to treat it all as the same thing. There's more than one way to be black.

One of my favorite pieces in the book is by Djibril Sall, who writes about how risky it is being queer and black in public spaces, which goes against a severe version of manhood he was taught by his upbringing and surroundings.

Bryan: Djibril is one of my favorites, too; he's a homie. The hardest thing is the biggest perpetrator of that kind of hate is other black men, but it all stems from white supremacist patriarchy as a way to pit dudes against each other so they feel undervalued. You're so obsessed with a nail color or a lip color or anything that's left of center. The idea of toxic black masculinity is projected onto us and we embrace it like that's what we have to be in order to be seen as valid, and it's this vicious cycle that keeps us oppressed and not expressing ourselves authentically. Masculinity as a construct in general ruins a lot of shit for us.

When I was first telling people about this project, people were like shocked that I was trying to explore emotions from the perspective of black boys, and one annoying assumption was that I was featuring a lot of stuff about being gay. Why does emotional authenticity have to be equated with a type of gayness in a negative way?

Tell me about the design and curatorial process. And how you guys decided to collaborate on this project in the first place.

Bryan: Jeana and I designed it together, but most of the aesthetic vision comes from Jeana because of her graphic design background. We definitely gave a lot of thought to the cover, with the parental advisory sticker and such. As much as it's not about rap, it's always about rap. The original storytelling. She used Illustrator and hooked up the formatting.

The best thing for me initially when it came to the layout for this is we basically printed out all the submissions and then laid them out on the floor and basically storyboarded the book from there. We took most of what was submitted and organized it, mostly because of the fact that people believed in the project. That was enough for us.

Jeana Lindo: We are actually best friends. We met two summers ago at an Oshun concert and then went on vacation together last summer. We were around all these white kids creating cool shit and we just thought about how there was a void with Black Boy Feelings. We wanted to make it a hashtag. To that end, Black Girl Magic was also an inspiration for us. Also, visibility is very important to us. As for me, I'm a big fan of movies and I'm always thinking about how stories about us are told. I'm always interested in us being the stars of our own stories and being portrayed as people with depth and range. We came upon this idea and it was immediately obvious that this is what the world needed.

How about the cover? How did that come about? It's very on-trend with the baby photo album cover and has a Kendrick Lamar good kid, m.A.A.d. city vibe.

Lindo: I really wanted to put Richard on the cover, and we were obviously inspired by rap album covers of late. Plus, frankly, we don't see enough little black boy babies in the consciousness of culture.

Can you tell me the reason you decided to publish this independently?

Bryan: For us by us, you know, But when we were working on it, not only was this an art piece but [it was also] a business [and] we'd have to get more people involved. We get the artists involved by having them sell their merch and come to events we are hosting. Publishers are mad expensive. It's kind of like, fuck a label until they give you the bread you deserve. Maybe for the second or third book we'll start a publishing house at some point. Maybe if Penguin or Random House cuts that check, but we're already not making money. It's a full labor of love.

On a personal note, I've always been very in tune with my sensitivity and i think that vulnerability is a character asset and not a weakness. There is this idea that is promoted by the white patriarchy that if you are black and male and speak from the heart, people think that your point of view is inherently violent.

Bryan: A lot of people hate me because I love them more than they love themselves. And, to me, that's because a lot of people don't experience love, understanding and affection. Black people are the strongest people on earth. We've been enslaved and poisoned and dumbed down, but when black people start uniting people become afraid. It's interesting that you look at the most peaceful stuff uplifting the black community, like the entire Civil Rights Movements and it's perceived as dangerous. It's sad but it's nothing new.

This feels obvious to ask, but: How connected is this project to movements like Black Lives Matter, and more visibility for the emotional experiences of black men, as seen prominently and recently in Barry Jenkins' Moonlight?

Bryan: It's everything. Black Lives Matter is facts. Black Girl Magic is facts. There are people who need to be safe, to feel safe. The hope Jeana and I have is that this book helps foster a safe space for black male visibility and expression. By the way, people do ask us: "in light of Black Girl Magic, when will you do a Black Girl Feelings book?" Our answer to that is, yes, black women still get stereotyped for being aggressive and angry. But there's still a void where we don't talk about the emotional nature of black boys. I saw Moonlight on the plane when coming back from New Orleans. It was important to see that, but you never really saw the main character dealing with the ramifications of growing up, he's like trapping and becoming hardened, but I did wish they showed you how he progressed. This whole thing is like -- everyone's opinions and art is valid. Do whatever you want and stay sharpening your sword.

What next for you?

Lindo: We have a plan for three books. The second volume -- we all want people to submit for the topic: Things My Mother Taught Me by July 21. Our own publishing company would be cool. Then, who knows, maybe world domination?

If you are interested in submitting original art or writing for Vol. 2 of Black Boy Feelings, visit Richard and Jeana's Facebook page for submission details. The deadline for submissions is September 30th.

Vol. 1: Boyhood is now on sale here.

Splash photo: Art by Chris Lee