Devin Allen grew up near Sandtown-Winchester, the neighborhood that Freddie Gray called home before he was arrested and killed in a police van in at the young age of 25 in 2015. Allen was already an experienced protestor, and was getting his feet wet as a photographer after discovering that he not only had a passion for it, but an uncanny eye for striking images that told far more than a thousand words stories.

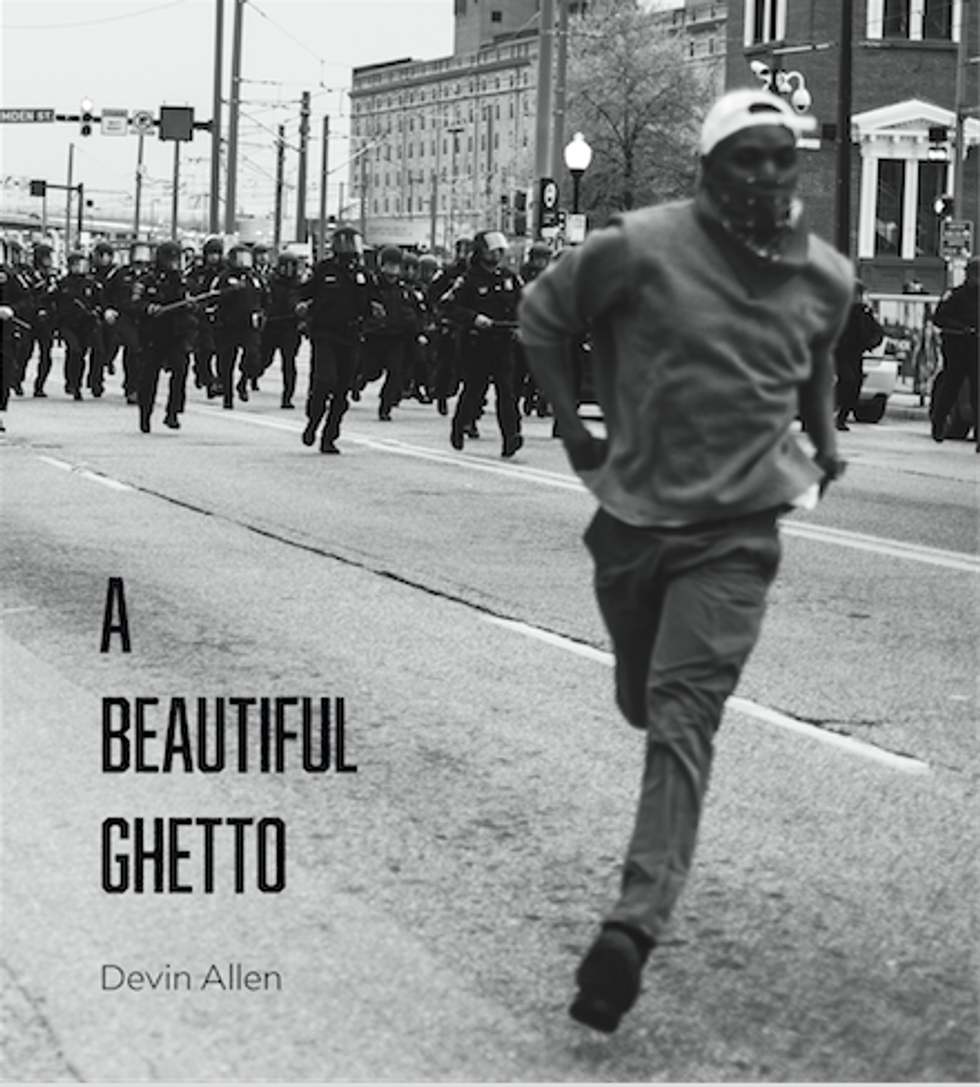

Gray was a year younger than Allen when he died, and the photographer suddenly found himself, like so many residents of Baltimore, surrounded by protests and a community enraged by another young life taken without consequence. He did what he had learned to do in these - and all - situations, and picked up his camera and took to the streets. He soon captured an image that ended up on the cover of TIME, making him one of three non-professional photographers to land that spot in the magazine's nearly 100-year history. He soon found himself, like Baltimore itself, on a global stage, as his photo was shared by BBC, CNN and even Rihanna - putting millions of eyes on his work.

Now Allen has a new book out, A Beautiful Ghetto, which pulls together 100-black-and-white photographs he took of both the uprising and of his hometown. We caught up with Allen to talk about his book, outreach program in his community (Through Their Eyes), and what it means to be a photographer capturing one's own history.

PAPER: I read that you're self-taught. When did you really feel like photography was going to be something you wanted to dedicate yourself to?

Devin Allen: I think the sign was after I got my camera. Losing both my best friends in one weekend, that kind of pushed me to take it more seriously.

PAPER: You lost both of your friends in one weekend?

DA: Yeah, one was killed Friday and another was killed Saturday. The only reason why I wasn't with them is because I was somewhere taking pictures. When I got into art, I performed first and I did that for a year or two. I didn't like performing so photography allowed me to show my work without saying anything. In 2013 - that's when I got my first camera.

In January, my friends were murdered. When I found out my friend was shot Friday, I was in the house actually editing pictures. Then the second day I went to go see his mother and everything. After that my other best friend was with me and after I left, he was shot in the head around the corner. It's heartbreaking, but it inspired me. It inspired me to take this seriously and dive into it while maxing out a couple of credit cards.

PAPER: And two years later, it was Freddie Gray and the uprising.

DA: Yeah it was two years later when everything happened in Baltimore.

PAPER: How did that experience affect your relationship with photography?

DA: It actually made me understand not just my role, my gift. Photography is not just my gift, but it's actually what I'm good at. I'm good at creating a conversation. A lot of people call me a journalist, but I'm not really a journalist because I push images to create a conversation. That's what I did documenting Freddie Gray and the uprising. You don't really understand how powerful it really is and how important it is to move it forward. Also, just documenting and making sure that the stories are told correctly. We're in a day and age where we don't believe anything in the media if it's not told correctly. That's something that has been happening for a long time.

PAPER: Could you talk a little bit more about creating images? How do you do that? What do you look for?

DA: It's all about how it connects to people. There's no such thing as a bad photograph I believe. When I create images I just make sure that it's not about how sharp or how clear the image is, it's about 'how can I connect?' That's the only goal, is to make someone feel something. If I could make you feel happy, sad, angry, then my job is done. It's about creating through my perspective. So when I'm shooting I always make sure that I love what I shoot, or that I have some type of connection to it. The subjects that I shoot, I can connect to. For me, creating images is all about how am I portraying it while documenting it.

PAPER: What was it like to be in the thick of those protests? It was your city and your people, but you were there as a photographer. What did that feel like?

DA: The crazy thing is when I'm there, I'm not just a photographer. I'm also protesting. Sometimes I just put my camera down and I get involved in the chants and everything else.

Just being in the uprising was kind of like a movie. You watch these documentaries about civil rights and see the things that happened in between protestors and police officers. It feels unreal. It makes you feel like how far have we come to be thrown into moments like that. It feels like things have settled for a while just to erupt again.

PAPER: What was it like to have such an enormous reaction to your work?

DA: Unbelievable. Coming from a small city like Baltimore, I've never expected it to be anything like this. Just to be having the cover on TIME Magazine, it's inspirational. That's probably the biggest thing -- that the kids are inspired by what I'm doing.

PAPER: I wanted to ask you about your travels. Your favorite places you've been. Other places you would like to go and photograph. What it was like to get perspective on Baltimore when you went away for the first couple of times.

DA: I'd never traveled prior or been overseas. The furthest I'd traveled was to North Carolina, and I've been to New York a couple of times, and I've been to Miami. I never really traveled too much, I was always in Baltimore. Mid 2015, Under Armour reached out to me. They were like "Hey you're on a shoot with Steph Curry." I was scared. I never left the country before and they put me on a sixteen-hour flight to Tokyo. The first time I left the country, I went to Tokyo. That was my first real job. I really got paid. It was amazing.

PAPER: What's the "Through Their Eyes" project?

DA: I've been working with the youth. The same year that I got the TIME cover and while I had all of that media attention, I wanted to give back immediately. I wanted to turn that unfortunate situation into a positive. I wanted to teach inner city kids photography because I just felt that would be a different perspective of the world and it should be shared. I felt photography helped me through all of this pain. I'm still learning photography, but I know the basics. I started a Go Fund Me and got a good response. Even the guy who started Go Fund Me liked the work and he donated a thousand dollars.

Russell Simmons was looking for me and wanted to help. He took care of everything that I needed. He gave me a twenty-thousand-dollar grant which allowed me to buy cameras and give them out. I also started working with kids over the summer who have disabilities.

If someone comes to me and says, "my child is into photography and can't afford a camera," I can give them a camera. So I work directly with kids, and some kids I give them my number and my email so that they can reach out. I've given out not just fifty cameras alone in Baltimore, I've also donated 18 film cameras.

PAPER: What's it like to see kids discovering photography for the first time?

DA: It's cool because a lot of kids are on Instagram and Twitter all day taking selfies. They have an eye for photography, so let's develop that eye. Just to see when they first learn, they have no idea what they're doing. But they think they know everything. I just like the interaction and teaching them. In Baltimore growing up there were drug dealers around me. I looked up to drug dealers because that's what was around me. I didn't know any lawyers or doctors. I know how hard life can be. I've been through things growing up. I want to help them more and be great also. Working with the youth is something I really want to do, because they are the future.

Splash photo by Adrian O. Walker