Kesha cried in front of a room full of journalists at a London playback for her latest album, Rainbow, in June of 2017. At first, she apologized, conscious she might be making them uncomfortable. But she quickly rebuked herself: "I'm not actually sorry," she told them. "'Cause that's what this record is about — being vulnerable. This is what I am."

The moment, captured by The Guardian's Laura Snapes and Metro UK, was a public, unapologetic embrace of vulnerability: something at the heart not only of her third album, but also the wall-to-wall rebranding Kesha underwent around its release. Musically and personally, Kesha left the defiant, snarling party animal behind, and re-emerged from her legal battle with producer Dr. Luke still glittery, but a newly tender and sensitive feminist icon.

"Vulnerability as a strength" became Kesha's tagline and rallying cry on her comprehensive Rainbow press tour. "I've written a record that reveals my vulnerabilities, and I have found strength in that" she wrote in an essay for Lenny Letter, calling Rainbow "the most real and raw" art she's ever made. She offered a similar spiel in Refinery29: "I let myself be 100% genuine, vulnerable, and honest." A New York Times profile titled "Kesha, Interrupted" reported that with Rainbow, Kesha set out to prove that "you can be a fun girl. You can go and have a crazy night out, but you also, as a human being, have vulnerable emotions."

Vulnerable Kesha was received with gusto by the press, which happily parroted the words back to her: "Rainbow's greatest triumph is how Kesha holds onto that vulnerability" claimed Slate, while Stereogum praised her "soul-bearing vulnerability." Consequence of Sound called Rainbow an album "ruthless in its commitment to vulnerability."Rolling Stone echoed: "she wants to be human, to be vulnerable, to let her life veer off-pitch once in a while..."

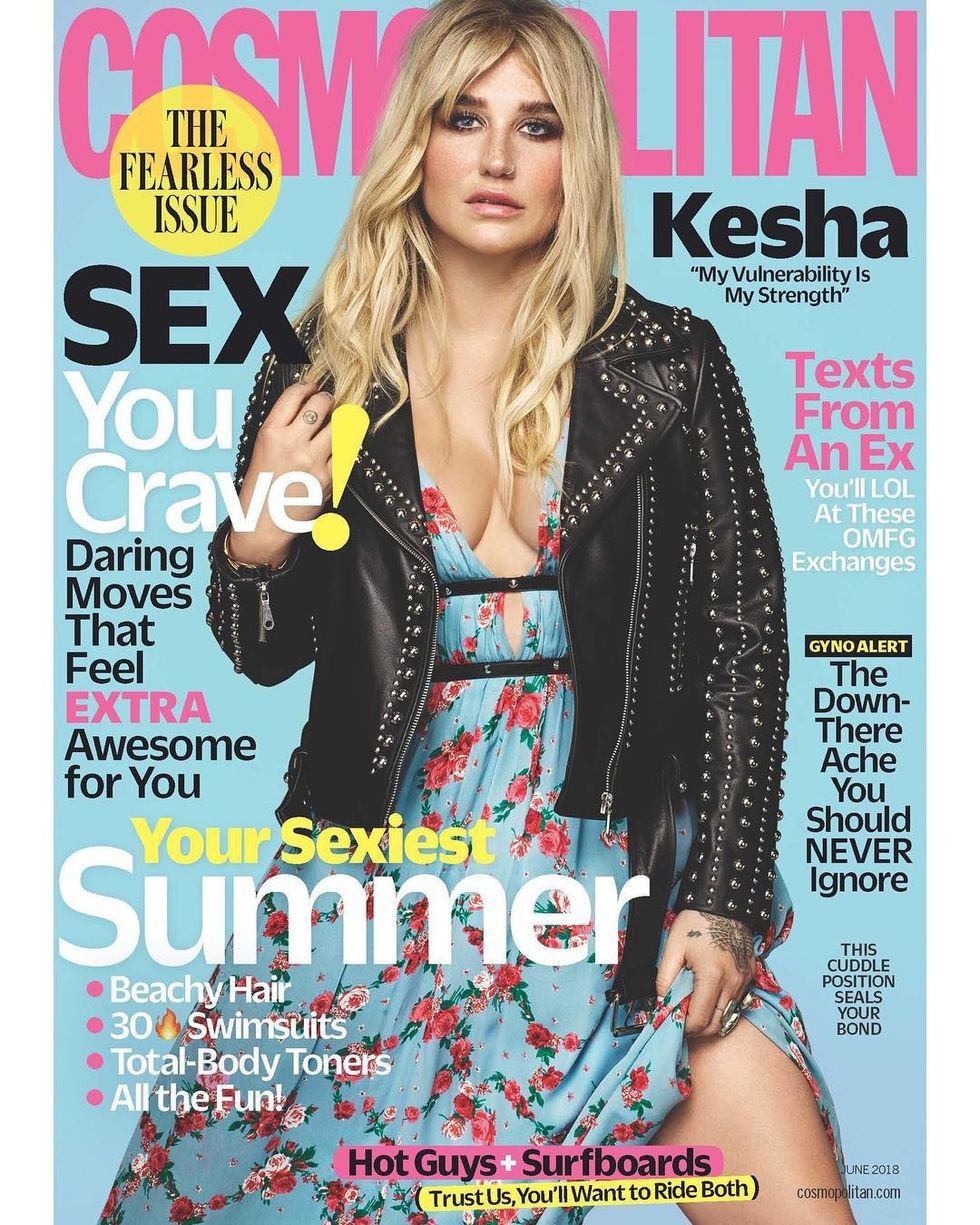

Maybe the most striking clip is Kesha's June 2018 Cosmopolitan cover, which was deliberately, if bluntly styled to emphasize that Kesha is wearing her wearing her pain and struggles on her sleeve. She gazes out from under smudgy eye makeup with a pained expression, awkward against the brightly colored spread and her girlish ensemble. She looks miserable. Her aching appearance underscores the tagline floating above her shoulder: "My Vulnerability Is My Strength."

Cosmopolitan / Jason Kim

It's a remarkable phrase to read on the cover of Cosmopolitan: a magazine that advertises itself as a bible for "fun, fearless females." For decades, titles like Cosmo — among the best-selling young women's magazines in the U.S. — have offered a window for the critical reader into the matrix of rules, regulations, ideals and aspirations that define American womanhood. For a long time, the stylings of femininity that glossy lifestyle magazines celebrated sounded much more like the old Kesha — the feral, carefree pop rebel, a picture of chill-girl confidence, always down for a laugh — than the afflicted woman who graced last summer's issue.

Commandments of desirable, healthy American femininity have long included self-esteem, happiness, confidence, resilience, and a positive outlook. Our collective dreamgirl is outlined by a 2006 list of "Cosmo Girl commandments," proposing that the model girl-citizen should "laugh in the face of danger," be confident enough to "ask a man out without perspiring," and feel so assured of her talents that her work computer password is "youareluckytohavemehere."

"Most men agree that a confident, secure, optimistic and happy woman is easier to fall in love with than a needy, neurotic one" advised Glamour a few years later, around 2009. Would Kesha's preoccupation with her own propensity for injury, insecurity and shame have landed her a Cosmo cover or a glowing Glamour feature (praising her swap of "glitter and Jack Daniels for vulnerability") back then? When, exactly, did "vulnerable" find its way into the list of breezy adjectives that describes the ideal modern woman?

Today, women who make themselves vulnerable in public by speaking about the kinds of traumas apt to render them, per Glamour, unattractively "needy and neurotic," can be confident they'll be cheered on — at least by liberal and women's media — something that was not a given even just a decade ago. Just look at the left-of-center media's reaction to Christine Blasey Ford's testimony against Brett Kavanaugh. CNBC and Politico both ran think pieces praising Blasey Ford's vulnerable appearance, — her shy demeanor, quivering voice, and admissions of being "terrified" — arguing that it was crucial to her credibility. Cosmo could be found cheering on their new girl power symbol: "Christine Blasey Ford and the Myth of the Weak Victim." As Politico points out, in the same seat 28 years earlier, Anita Hill couldn't have presented herself more distinctly: "She was a rock: understated and confident, steely and cool, staring down the senators." The behavior of a woman trying to convince an entire country she's telling the truth on national TV is surely a litmus test for the type of femininity we desire, maybe even a more accurate one than beauty magazines.

If we go just a few years back, the idea that a woman facing public scrutiny should lean into vulnerability rather than aspiring to confident poise — or could do so without being described as overly-emotional, hysterical or self-victimizing — was far from conventional wisdom. In between the era of the "fun fearless female"s reign and Kesha's embrace of the term, the modern ideal got a makeover. Sometime during the late Obama years — after Beyoncé sampled Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, but before Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 presidential election — feminism became mainstream. At the dawn of this era, the halter-topped, sexually empowered Cosmo girl morphed into an intrepid, entrepreneurial #girlboss: an even more tenacious, but now-pantsuited character, who wouldn't be caught dead crying at a public speaking event.

Vulnerable was a dirty word you'd call a woman to insult her, under the reign of "manifestos" like Sheryl Sandberg's Lean In: Women, Work and the Will to Lead (2013) and Katty Kay and Claire Shipman's The Confidence Code (2014). The leader of this moment of cultural feminism, Sandberg proposed that the most crucial barriers women face, are actually the internal ones they create for themselves. Though she disputes this reading, millions of women interpreted Lean In as a call to "man up:" an imperative to abandon femininity, and instead, adopt normative masculinity: toughness, aggression, strength and volume. Women were told they should and could fight to the top of the boys' club, sometimes, through adjustments as simple as cutting down on apologies and striking "power poses," as psychologist Amy Cuddy suggested in a 2013 TED Talk, rather than question why such traits are viewed as leaderlike in the first place. As Jessica Valenti put it, Lean In successfully convinced millions of women that what is "truly holding [them] back is their own self-doubt."

Lean In, according toThe Nation, debuted with Gloria Steinem and Beyoncé's endorsements and rode the New York Times' bestseller list for over a year. Over 4 million copies having currently been sold, and two and a half million more people viewed Sandberg's 2010 TED Talk, a prequel of the book. Today, 12,500 copies still sell each month and thousands of "Lean In" circles (Sandberg bible studies, spaces "where women can be unapologetically ambitious") meet monthly around the country.

With their massive audience, Sandberg and her ideological peers reinscribed the familiar notion that confidence is the most important quality of a successful, desirable woman — as well as the key to finding success in the existing system. This obsession with women's confidence, now in the explicit name of feminism, wrote London University professor Rosalind Gill in her 2017 essay "Confidence Culture and the Remaking of Feminism" for the journal New Foundations, rendered "insecurity and lack of confidence as abject and abhorrent. If confidence is the new sexy, then insecurity... is undoubtedly the new ugly... Self-doubt and a lack of confidence are presented as toxic states."

Obviously, Lean In had immediate critics. Aside from Jessica Valenti's concern with who shouldered the burden of change, bell hooks wrote in her 2013 review for The Feminist Wire, "Sandberg's definition of feminism begins and ends with the notion that it's all about gender equality within the existing social system..." Jacobin's Melissa Gira Grant charged that Lean In "centers the concerns of an elite minority of women" and "repeats the losing tactics" of past feminist movements, which were "insufficient in addressing inequalities among women." Trickle-down feminism doesn't work, argued The New Republic's Judith Shulevitz, because women won't become good or ethical or feminist leaders if they can only succeed through conformity: "Competent female executives run better companies than incompetent male executives, but they're no more likely to make universal day care the law of the land."

Once the stuff of leftist magazines and academics, today Lean In has been challenged by everyone from Michelle Obama to Sandberg herself. "It's not always enough to lean in because that s*** doesn't work," Obama quipped recently at a stop on her book tour. Sandberg, meanwhile, has admitted that she failed to account for the difficulties faced by groups like single mothers, a demographic she now finds herself a part of, in the wake of her husband's untimely death. The internet is littered with studies questioning Lean In's efficacy in light of women's plateaued progress since 2013 (by metrics like the number of female Fortune 500 CEOs, at least) and staggering evidence that women are often subtly penalized for the kinds of workplace for the assertiveness Sandberg recommended. "How Lean In failed me"-style personal essays, written by former disciples, about how damaging its illusions are also abundant. Most mainstream outlets have published one of each.

"Lean In Has Been Discredited For Good" declared The Nation, which once reviewed the book positively, after the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke in November. Positing that the Facebook executive was just another example of a female leader who will act just as unethically and unscrupulously as a male counterpart, when given power, the author asked, "Why would women aspire to be like Sandberg?" Facebook and Google alum Marissa Orr is making a beeline for Sandberg's disaffected audience seeks with the first definitive corporate rebuttal. Her book, Lean Out: The Truth About Women, Power and the Workplace, promoted as "the antithesis" to Lean In, promises to "reexamine the business world's paradigm of a 'successful leader'" and "expose corporate dysfunction as the source of the nation's gender gap."

Given unsubtle titles like these, we don't need Kesha's Cosmo cover to see that women have lost faith in Lean In's promises. However, her glossy grimace is a clue that our culture's fatigue is with more than just the bestseller. Insofar as we project our desires onto celebrities, and celebrities model themselves based on our desires, Kesha's public vulnerability hints that we may, finally, be moving away from the cult of confidence that has defined American womanhood for decades, and the often unlivable model of femininity it prescribes.

Kesha is far from the only celebrity adopting these catchphrases. Lady Gaga built the term into her brand around 2016's Joanne (marketed as her "vulnerable" album), her documentary Gaga: Five Foot Two, and her revealing role in A Star Is Born. Billboard quotes Lady Gaga at a press conference for Five Foot Two, in which she spoke about her PTSD as the result of a teenage rape and chronic pain due to fibromyalgia: "to touch on that idea of vulnerability... there is a degree of self-deprecation and shame that comes along with feeling in pain a lot, and I want people that watch it... to know that I struggle with things like them... and that I don't have to hide it because I'm afraid it is weak."

The media has amplified and cheered on her newly softened persona. A Hollywood Reporter roundtable from this past Oscar season featuring Gaga, Glenn Close, Kathryn Hahn, Regina King, Nicole Kidman and Rachel Weisz was titled: "The Actress Roundtable: 'Vulnerability Can Be A Strength.'" The title quote is Gaga's. "Lady Gaga Is The Most Vulnerable Pop Star In The World" claimed ELLE in their review of Gaga's "Enigma" Las Vegas residency, praising how, during the show, she displays the "raw edges of her struggles."

Likewise, Selena Gomez and Demi Lovato, two celebrities who've struggled publicly with mental health and addiction, have used the rhetoric of vulnerability to take control over their narratives. In the wake of sensitive moments that might once have been reported on as as embarrassing scandals, the media has embraced them. "How Selena Gomez Turned Vulnerability Into Her Greatest Strength," blared a 2016 Mashable headline after it broke that she'd entered rehab. Gomez later repeated the idea herself. "I think strength is being vulnerable," she told TIME. Lovato similarly promised in 2017 to be "completely vulnerable" in her new album and documentary, with regards to her struggles with mental health and addiction.

Even Beyoncé, of the Sasha Fierce alter ego, has embraced vulnerability, or at least by media consensus, become its champion. "Beyoncé's Lemonade and the Undeniable Power of a Black Woman's Vulnerability" read the headline of a Vulture essay, while on Lemonade, wrote ThinkProgress, "through vulnerability, Beyoncé displays her power." Glamour argued that Lemonade "gave Black women permission to be emotional without shame." This year, Refinery29 praised how Beyoncé "continued her "Year of Vulnerability" and her announcement that she's "done being perfect" in her September Vogue cover story, in which she described feeling "neglected, lost, and vulnerable." Zooming out on the Knowles-Carter empire, VIBEobserved that with their trio of intimate albums, Lemonade, 4:44 and Everything Is Love, Beyoncé and Jay-Z quietly "rebranded themselves as vulnerable, endearing superstars."

Kesha, Gaga, Demi, Selena and Beyoncé have become associated with the term "vulnerability" via divulgences of specific traumas, from infidelity to addiction. Others have taken up the mantle as an everyday aspiration. In January, Hailey Baldwin Bieber shared a New Year's resolution with her 17 million Instagram followers: "stepping into 2019 I want to be more open, I want to be more open about the things I struggle with, and be able to be more vulnerable. I'm a 22 years old, and the truth is no matter how amazing life may look from the outside I struggle... I'm insecure, I'm fragile, I'm hurting, I have fears, I have doubts, I have anxiety, I get sad, I get angry."

---

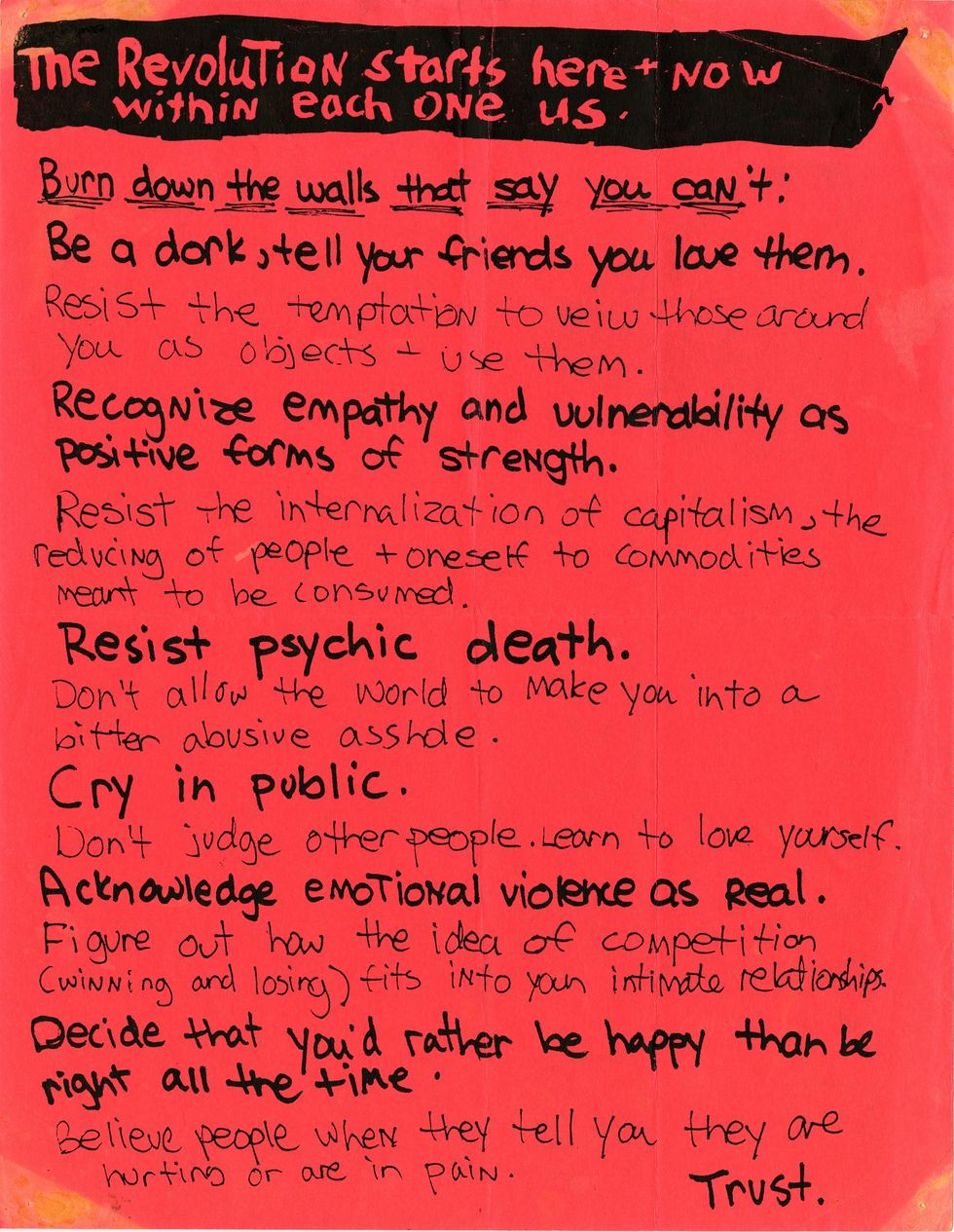

Over the years, feminists have thought a lot about the meaning of vulnerability. In academia, Audre Lorde, Judith Butler and many others have written books about its potential as a radical political fuel that, if truly recognized, could end wars and save lives. Feminist literary hero Joan Didion has been credited with challenging the gendered dichotomy between frail and strong, vulnerable and powerful with her hurting heroines and complex public persona. A flyer made by Bikini Kill's Kathleen Hanna in the '90s instructed her Riot Grrrls to "recognize empathy and vulnerability as positive forms of strength" and to "cry in public." Much more recently, DIY feminist artists and writers (often on Instagram) have proposed popular mantras about its resistant and revolutionary power, like Audrey Wollen's "sad girl theory" which suggests that a women's negative emotions can be an act of political protest and Lora Mathis' viral pieces surrounding the notion of "radical softness as a weapon."

Kathleen Hanna's Riot Grrrl manifesto circa 1990's / Courtesy of Fales Library and Special Collections

While the mainstream embrace of "vulnerability as a strength" reflects a pivot from the Lean In model of desirable womanhood, there's little evidence that this trend is being complemented by a radicalization of mainstream feminism. Kesha, Gaga, Demi, Selena, Hailey and Beyoncé all identify as feminists (the standard for celebrity women), support LGBTQ rights, #MeToo, and #BlackLivesMatter, and endorse Democratic political candidates. But they rarely express political ideas outside of generic liberal talking points. Though they'd likely agree with several of Hanna's riot grrrl rules like "believe people when they tell you they are hurting or in pain," they'd perhaps be less comfortable with her call to "resist the internalization of capitalism, the reducing of people + oneself to commodities meant to be consumed."

Gill questions if we might see "vulnerability be just as co-opted and commodified by corporations as confidence and female empowerment." Perhaps nothing illustrates the importance of a critical eye towards trending vulnerability more than the Kardashian-Jenner's timely culture's new interest in women's vulnerability.

"I'm so proud of my darling @KendallJenner for being so brave and vulnerable" Kris Jenner wrote on Instagram, previewing a mysterious video that Kendall would drop that weekend (terms uncomfortably similar language used to talk about how products like sneakers and albums are dropped). Kendall's "most raw story" turned out to be a paid sponsorship with skincare brand Proactiv in which Kendall "confesses" that she's struggled to feel good about her skin. The ad drew backlash from those who found it insensitive for Kendall to suggest that overcoming acne is heroic. Others defended her, arguing that even women armored with money, conventional beauty and privilege deserve the right to feel vulnerable — and to make money off that vulnerability.

Kendall's ad warns of the precarious heights of vulnerability rhetoric's rise. On one hand, her use of the rhetoric points to a remarkable level of consumer consensus around vulnerable femininity: when a Kardashian-Jenner deems an idea profitable, you know they've run the numbers. This isn't to say that Kendall's insecurity about her skin is insincere. However, branding choices like Proactiv's ad are based on perceptions about what people desire and believe. The ad and its roll-out were designed based on a novel new normal: that vulnerability is positive and powerful, something to champion in your daughter, not something you teach her to hide. On the other, the backlash against her highlights how quickly vulnerability becomes contested, as more people claim it over mundane, banal or privileged challenges. Even though what Kendall's doing isn't all that different from Kesha or Gaga's teary speeches, in the end, her monetization of her own insecurities undermines the credibility of her language and others amplifying it.

Speaking to these tensions, Jane Juffer, a professor of Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Cornell University, surmises: "The branding, that's what ties it together. Vulnerability has become a brand, and a marketing category. However, I would not by any means dismiss that because branding can be powerful. Consumer activists have used branding to make consumers into political activists. I think that has a lot of potential."

Whatever its potential, there's clearly no direct link between celebrity invocations of "vulnerability" and the term's radical feminist legacy. These empowered, vulnerable celebrities' ideas appear more rhetorically similar to the apolitical pop psychologist Brené Brown, whose TED Talk, "The Power of Vulnerability," went viral in 2013. The 20-minute talk suggested that "listening to shame" and sitting with vulnerability could be a secret to happiness, and a birthplace "of creativity, connection and change." She's been championed by Oprah, who, as Editor-in-Chief of Bitch Magazine and author of We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl Andi Zeisler points out, was among the first celebrities to leverage vulnerability as a part of her brand. Nonetheless, the journey of this rhetoric, even if it's just from the maternally coded domain of Oprah and self-helpy TED Talks to young starlets' Instagrams, still feels remarkable.

---

Given that social media is a central sphere where these vulnerable confessions are made, the rise of our interest in women's vulnerability feels inextricable from our relationship to the internet. "People who grew up on the Internet just have a different level of comfort with being vulnerable with sharing parts of themselves, whereas I think generations before saw so many examples of people — particularly people who aren't white men — being punished for merely being honest about their lives," hypothesizes Zeisler.

Beyond the general phenomenon of our increasingly translucent lives, in recent years, we've witnessed an online referendum on empathy. Gill speculates that "a key driver of [the rise of vulnerability rhetoric] is a reaction to hate and social media toxicity, especially among such high profile celebrities who are on the receiving end of extraordinary volumes of criticisms, attacks, threats. The embrace of vulnerability is connected to a desire to promote kindness... a reaction against hate in the wider political climate."

There's no better benchmark for how much our online space has evolved than a look at the climate that Lindsay Lohan and Amanda Bynes weathered in the 2000s and early 2010s, as compared to the one their child-star counterparts, like Demi and Selena, encounter today. While Demi and Selena can confess their afflictions online and assume they'll be met with support, in the mid-2000s, when Lindsay Lohan was in and out of court and rehab, and, later, when Amanda Bynes was tweeting in an amphetamine-fueled spiral, they were viewed and reported on as pathetic scandals.

It doesn't seem like a coincidence that Lohan — who endured some of the Internet's cruelest years as a young woman, who was never allowed vulnerability without ridicule — was one of the few female celebrities to criticize #MeToo, equating vulnerability with weakness. "I think by women speaking against these things, it makes them look weak when they are very strong women," she told British magazine The Time.

Trolls will still make quick work of mocking visible women's perceived imperfections, but on an increasingly sincere Internet — newly concerned with privilege, power, mental health, addiction, and sexual violence — humiliating women in crisis is not the sport it used to be. It's hard to say how, if Lindsay or Amanda had tried out being "raw" and "vulnerable," or if Kesha's Rainbow moment had happened five or ten years ago, these women would have been received. I suspect, given our historic comfort with a dichotomy of pathetic victims and boss bitch warriors, we wouldn't have known what to make of a star insisting she ought be able to have both: vulnerability and dignity.

Celebrities are not activists, and Instagram posts wont dismantle the toxic ideals of our culture. However, the overhaul of vulnerability-as-virtue has undeniably feminist implications. For too long, and too often in the name of feminism, women have been punished for their "vulnerable feelings," insecurities, self-doubt and shame, which in reality, are a generally appropriate response to how the world values them.

Although their soundbites don't appear to have much political depth, when Kesha or Lady Gaga say "vulnerability is a strength," they suggest awareness of how oppressive the demands placed on women in the name of their own uplift and empowerment can be. They propose that women should not be required to perform happiness or confidence in order to be seen as strong, powerful, or leaderlike. They claim that women should be able to express emotion, without being seen as sentimental or pathological. Insecurity, without being read as neurotic or needy. They endorse the simple notion that existing in the world as a woman is a vulnerable experience. As Baldwin puts it, "I'm a young woman, I'm learning who I am, and it's REALLY FREAKING HARD." Their words, potentially, offer relief from the kind of shame, that is born from the punishment of shame itself.

---

The celebrity uptake of vulnerability can't be separated from performativity and branding, but that doesn't mean it's not significant. "With the branding of vulnerability, it becomes possible to claim vulnerability and to be vulnerable without being a victim. And I think that's great, if we're talking about redesigning femininity. For years femininity has been associated with vulnerability, but in a way that described women's weakness and inherent potential to become victims, whereas now, it's giving us a way to talk about strength" suggests Juffer.

Each scholar who commented for this piece expressed both excitement and skepticism about the implications of the vulnerable heroine's rise to grace. "How is the entitlement to vulnerability socially distributed? Who gets to be allowed to be and express vulnerability? Only those who are already rich and powerful?" Gill asks. Zeisler warns: "I don't want to see vulnerability become something else that marginalized groups have to perform to prove that they are human." She queries if we might be looking at a backlash a few years down the line, when culture decides it's heard enough about all this new age vulnerability stuff, and returns to recognizing a woman crying at a business event as hysterical, disgraceful.

In between all these complex, crucial questions, is the thought of a teen girl coming of age in a time when powerful women are praised on magazine covers for being vulnerable and honest about their pain. As such, it's easy to be left with the ambivalent sense that this shift both means something indelibly significant for women, and nothing at all. Just the latest window-dressings on the same flawed model.

Rich and famous women's words, and the headlines written about them are not changing the world. But they do hold up a mirror to our own cultural sensibilities and appetites, and for better or worse, that reflection is transforming.

Photos via Getty