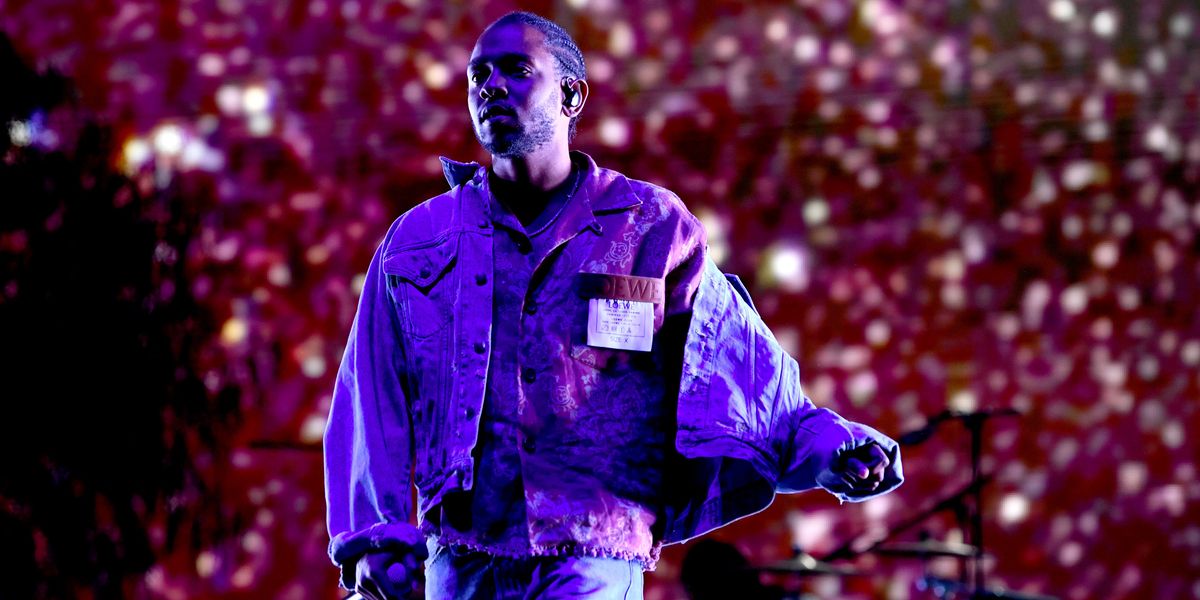

As my friends and I pulled into the venue for Top Dawg Entertainment's Championship Tour, the record's label first co-headlining concert featuring artists such as Kendrick Lamar, SZA, and Schoolboy Q, I thought to myself, "I ain't never seen so many white people in my whole entire life, and I'm from Texas." The masses of young white attendees (and for those underage, their accompanying parents), all in designer gear, illustrated the overall mood and climate for the TDE tour stop.

Although the show was located in Washington, D.C.; also known as "Chocolate City" given that 47 percent of its residents are black, the composition of attendees reflected exactly which communities have access to attend a concert outside of the Metro limits on a weeknight. I was reminded of Beyoncé's headlining performance at this year's Coachella where she invoked the imagery of Southern Blackness in front of an overwhelming white crowd, and my place in this predominantly white space, although I was there to witness Kendrick Lamar and the TDE roster, arguably the most conscious mainstream rapper of this generation.

Throughout the Kendrick concert, I witnessed the disconnection between white attendees and the music, the blatant verbal disrespect when artists performed their deep cuts instead of their Top 40 singles, and the lack of attention for opening artists on the roster like Isaiah Rashad, S.I.R., and Lance Skiiiwalker. Yet, when Kendrick and Schoolboy Q performed any song with 'nigga' in it, white attendees shouted the word as if were their birthright. The amount of privilege to, as a white person, verbalize the n-word at a rap concert in a predominantly black city is a representation of power. A privilege that absolves its users from the responsibility of saying a term, representative of societal hate and violence. As evidenced by the white girl who said the n-word twice on stage with Kendrick Lamar at Hangout Festival in Alabama, white people possess the ability to disrespect black people's humanity in front of their very eyes.

Related | Kendrick Lamar Stops White Fan from Saying the N-Word on Stage

That privilege exists because black attendees cannot hold their n-word rapping white counterparts accountable. Who would believe black attendees over privileged white attendees? What black person would want to be told that their claims emerge from feelings of "sensitivity," "over-exaggeration"or "political correctness?" Followed by the classic response, "I said it with an a, and not the er," as if the removal of two letters erases the historical implications of the word from the American consciousness. The white experience in America is one of acquisition of property, and the latest commodity to go is hip-hop.

Lamar's genius for the ability to describe the complexities of the African American experience in the United States has contributed to historical and cultural shifts throughout the world over the perceptions of blackness. Evidenced by his award winning albums, from his earliest musical projects Section.80, Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City and Grammy winning To Pimp A Butterfly to the Pulitzer Prize awardedDAMN, and the narratives on Lamar's albums uplift the voices of marginalized black youth impacted by the stressors of state violence. Police brutality, mental health, mass incarceration and the impacts of Reagan era legislation that targeted low-income black communities like his hometown of Compton, California are all topics to be found on any Kendrick album, alongside hits like "Humble" that have brought him a level of mainstream success and fame considered rare for a conscious rapper.

These messages validated sections of my experiences, including being raised in a low income household, the continuous hustle to reach financial security for your family, and fighting to not only survive, but be alright. Kendrick's lyrics are also complemented by the artistry of TDE's full roster of entertainers. There's TDE's first lady SZA, whose desire, as a black woman, of wanting to be a 'normal girl,' can at times mean erasing the parts of self that do not align with white standards of beauty, and also Jay Rock, whose constant striving to win is reflective of the community black people share — an unspoken agreement of communal uplifting that originates from relationships built through generations of oppression.

Hip-hop is, after all, the Black American songbook. Woven into its medley of 808s beats and 16 bars are the stories of a people defining their space and place in a nation built off the sociocultural horrors of their enslavement. In the early beginnings of the genre, the music was utilized as an instrument of truth, where young black men like N.W.A. could describe their experiences to the world when the media said otherwise. Contemporary artists like Kendrick Lamar, J.Cole, and Vic Mensa stem from this tradition and incorporate its messaging into their music and create projects that possess the ability to influence generations of communities about what it means to be black.

The black experience in the United States has historically been commodified and sold for profit, at the expense of abandonment and pain. From white entertainers in blackface, to singing the n-word in rap songs, the fetishization of the black experience by white people is reminiscent of the larger social and power dynamics in this nation. That is, structures that give young white people access to the financial means needed to indulge in the pleasure of hearing Kendrick perform his masterpieces live, over their black counterparts who lack the same generational wealth and job opportunities due to the barriers that restrain the low income black youth who supported hip-hop's transition from underground to mainstream in the first place. We live in a reality where the black communities who gave life to a rapper's artistry are then not awarded a seat at the table of prominence.

Related | Kendrick Lamar, King of Our Hearts, Accepts Pulitzer Prize for Music

Moving forward, I'm thankful for the intentionality of black-centered musical spaces such as Broccoli City Festival and AFROPUNK, which celebrate the diversity of black experiences through the inclusion of the communities who built them at an accessible price. I'll always love hip-hop and the magic of a good concert — filled with unreleased freestyles and a fire 16 — but I now have to ask, "What's the cost of me attending this concert?" Is it going to be a continuous struggle of young white boys groping my ass and white girls asking me to twerk while I have to remain calm as white people scream "nigga" for hours, just out of pure privilege?

En route home from the TDE Tour, I thought about the words to describe my feelings of loneliness and rejection from the predominantly white concert space, but then, I turned on track 7 on To Pimp A Butterfly to let Kendrick remind me that black people and hip-hop gon' be alright.

Photo via Getty

From Your Site Articles

- Infinite Coles Breaks Out With "Lightning" - PAPER ›

- Catching Up With Kamaiyah on the Set of Her Next Music Video - PAPER ›

- Watch Lakeyah Rise to Fame in Her "Hit Different" Video - PAPER ›

- Jay-Z Wants Rap Lyrics to No Longer Be Used as Court Evidence - PAPER ›

- Kendrick Lamar Returns With "The Heart Part 5" Deepfake Video ›

- New York State Senate Passes "Rap Music on Trial" Bill ›