It's the age of multihyphenate creatives. New York's next generation of designers are muddling the distinctions between fashion, design, and art as never before. At New York Fashion Week Men's this July, Emily Bode presented furniture made in collaboration with Green River Project alongside her spring 2019 collection. Earlier this month, Mike Eckhaus and Zoe Latta unveiled their shoppable art-meets-fashion exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The latest name to join the chorus is Sam Linder, womenswear designer and co-founder of the namesake brand he helms with men's creative director Kirk Millar.

Related | Eckhaus Latta Makes Shopping an Art

Before the Vermont native was known for his nuanced eponymous label wrought with confident sensual energy, he was an inquisitive teenager with a camera. In his twenties, with no more training than an introductory photo class, Linder unwittingly set out on a lifelong process of examining perception and conception. "I've always been curious about how we receive information, construct our understanding of it internally, and how these two things alter each other," the 44-year-old explains at his debut photography show at The National Arts Club in Manhattan's Gramercy Park neighborhood. Titled Sam Linder Photo Works, the single-night exhibition was the culmination of more than two decades of photography focused on the cognitive process.

Organized in the 120-year-old art institution's expansive Grand Gallery, the show opens with Linder's 2002 book New York For the Aimless (Penny Ante Press). As opposed to fixating on a singular subject like a building, a person, or a car, the hazy images in this series show an entire field of vision, allowing one's eyes to determine what is and isn't noteworthy. Inevitably, these photos nudge preconceived notions and existing attitudes—a near-desolate park enveloped in a chalky light, a tranquil scene for some, may feel more sinister to others. While Linder's initial goal was to photograph without purpose, the human predisposition of ascribing meaning to images prevented him from doing so.

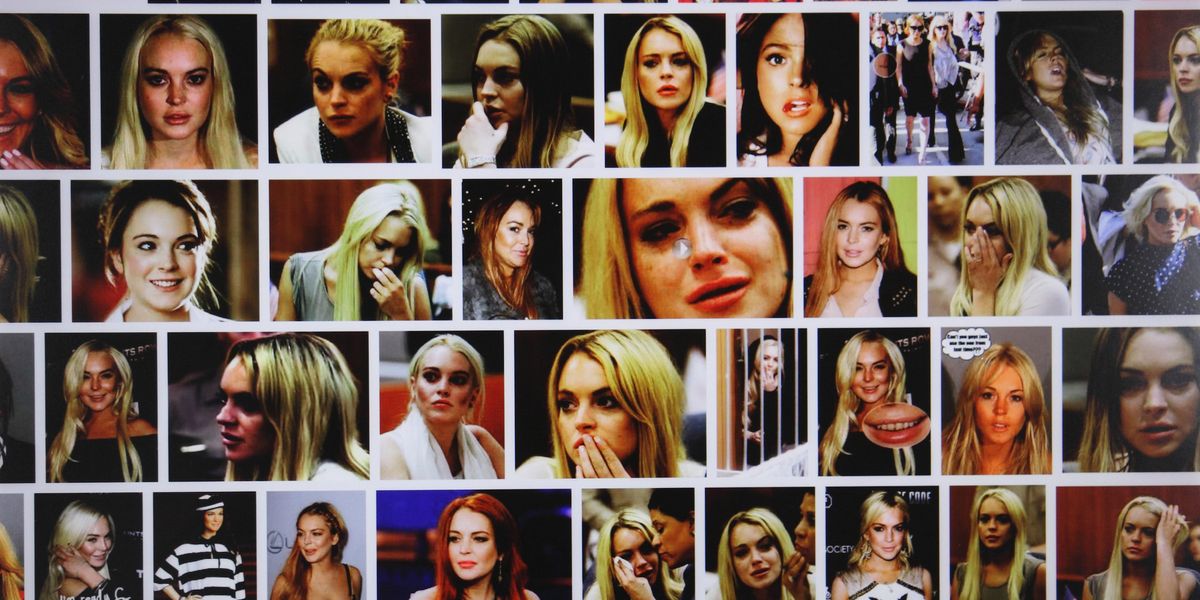

If ever there was a library of such word-picture associations, Google would be it. A series of 34 search engine image grids—focused on a range of topics from history and art to politics and pornography—titled "Search Results," Linder touches on a single word or phrase's ability to have breadth of visual representations. "If you search for melons, you get both honeydew and large breasts," Linder says laughing. Jokes aside, these image banks have the power to tell complex stories. One focused on Lindsay Lohan for example, captures the actor's highs and lows, personal and professional life, and even conveys public opinions of her through memefied pictures.

"Traditional photographs are three-dimensional objects," Linder says. "When they're uploaded to the Internet, they become two-dimensional data points." Although the works in "Search Results" appear to be screen grabs, they're truly photographs of screens translated to into C-prints. As opposed to printing pigments over paper, the colors in these images are the result of chemistry inside the paper that responds to light. Through this process, Linder reverses the digitization of the tangible world and reconstructs the digital realm as a physical one. "I have a hard time figuring out which mode of reality is more authentic," Linder admits. "So, I'm compelled to play with it."

Linder's contemplation on actuality and fantasy continues in a series of photographs of Hollywood actors' names in the opening credits of their films called "Titles." "These people are in the public domain," Linder explains, citing their godlike status in the collective mind. "They're human beings that exist between reality and fairytale." Celebrity names elicit a host of images and information, both biographical and fictional, related to the individual and the characters they've played. When seen in a specific design treatment like a bold sans serif typeface against a black background in the title sequence of Kill Bill, the existing characteristics associated with Uma Thurman's name may suddenly become attached to killer instincts and assassin-like stealth.

"I have a hard time figuring out which mode of reality is more authentic."

These thought-provoking images trigger an endless ping-pong match between digital and analog, reality and fantasy, and one's existing beliefs and methods of understanding the world. "This all took place before there was ever a Linder brand or even a notion of one," Linder says, outlining projects finished before 2013 when he established his eponymous label with Millar. The duo's collections have just hit their stride in the last year. While that may be reason enough to abandon photography, Linder has chosen to continue it. Maintaining the practice allows the designer to ruminate on ideas outside of the fashion sphere, but for Linder his thoughts aren't absolute. "I hope that there's a mystery to these works," he says. "Hopefully, that'll push the individual's perceptions beyond my own."

Photography Courtesy of Sam Linder