It has been three years. And in this last three years, I have looked at my life in Prince years front ways, sideways and a hundred other ways I've yet to comprehend. This year seems more significant than the previous two years with the actual anniversary of his death, April 21, falling on Easter Sunday.

I am a journalist who is often frustrated with the ways people of color are represented in the media. I can see why Prince hated being interviewed, was annoyed by certain questions and didn't bother trying to hide it. This oftentimes left writers equally annoyed with him and the round about way he had of never quite getting to the point — or, I should say, of never quite getting to their point. He always had his own statement to make, which didn't always jive with the editorial process. But, that was Prince being Prince, authentically striving to be himself. It was also some writers being quizzically lazy.

I learned this myself while being interviewed. I was asked who I would like to interview, living or dead, why I wanted to and what I'd ask. I thought about it for a moment, though I already knew the answer: Prince. The laundry list of questions I wouldn't ask is long, filled mostly with personal questions because I am of the belief that not everyone needs to know everything. But, "If you are going to tell it, tell it all or don't tell it at all" — words of wisdom I learned from my friend Regina Jones whose publications, SOUL Newspaper, SOUL Illustrated and writer Steven Ivory were among the first to cover Prince in 1977, just after he signed his first recording contract with Warner Brothers.

What would I ask Prince? "Where is the balance?" Why? Because when it comes to music, there's the profane, there's the profound and then there's Prince.

Musically, Prince found balance in this dichotomy of polarizing forces where profanity and sexuality were "nasty, but not dirty" (his words), and the profound tapped into both your subconsciousness and your spiritual being. In the end, he left you with a positive listening experience where at the end of every song, you found him standing there asking, "Can u relate?" Sometimes you do, other times it's just 5-7 minutes of "I don't get it." But, that's okay, maybe he didn't mean for you to. Not everything is for everyone to know.

More so than any other artist, Prince explored sin and the sacred, oftentimes in the same song, throughout his career. In his last three solo albums, you can see the maturity in his thinking as he developed a more existential self-awareness, where his sexual existence was no longer in conflict with his spiritual reckoning. His sense of spirituality was transitioning and transcending the religiosity that had become the hallmark of his earlier works. And sex, well, that's just something grown folks do and if they do it right, it can be equally uplifting.

It is impossible to come to this nuanced understanding of him as a man and as a musician without understanding something about music, especially without understanding Black music and the Black cultural experience that was the cornerstone of his upbringing.

Black music has three flavors: sexual, social and sacred. If you are of Prince's generation, think Millie Jackson (sexual), Marvin Gaye (social, though an argument can be made for the former, i.e. "Let's Get It On" being used in Reese's Easter commercial), and Mahalia Jackson (sacred). Prince's music was a Neapolitan blend of all three. That's why there are no real subgenres in his catalog. To pick one is to overlook the subtleties of his work where a song can be funk, rock and pop, all at the same time.

This unique blending of the three flavors is why his music, whether you can accept it this way or not, is Black at its roots, and it's all Prince. So understand that when he said, "I am music," he was acknowledging that at his foundation, he was Black music. His way was just to get the world to see how diverse it could be. When it was Purple Rain, it crossed over and served the masses. When it was The Rainbow Children, it didn't. Some will argue that the messenger changed by 2001 as the result of his becoming a Jehovah's Witness. Fans and critics should, however, consider that it wasn't the messenger who changed, nor did the message. Maybe all that changed was the delivery system through which that message was shared.

A perfect example of this type of flexibility in song is "When Doves Cry" and the pleasant or — dreadfully unpleasant —way it has been covered over the years. On its face, it is a song about complicated relationships, opens with a heavily rock-influenced guitar riff and proceeds without bass line. However, the video begins with what looks like the stained glass windows and door of a church opening and doves flying out from a room with scattered flowers, and a naked Prince in the bathtub. The song and the video that came with it demonstrates this seamless vacillation between the sin of seduction and repentance we pay for those sins. Therefore, it should surprise no one that this song was covered twice in 1996 in a way that was profound, using a church choir led by 12-year-old Quindon Tarver for the film, "Romeo + Juliet." Ginuwine, Mr. "If you're horny, let's do it," delivered the profane in a poorly produced cover by Timbaland, who has built a career using the 808 feature on drum machines and his own Teddy Riley, Roger Troutman style autotuned humming in place of traditional bass lines.

I realize some will challenge this notion. No fan base is unified behind one specific idea or outlook, interpretation. I find this especially true when it comes to Prince and his identity as a Black man. But we have to trust the words of people who shared that upbringing with him, like Andre Cymone. In our 2017 HuffPost interview, he acknowledged that when you grow up in Minnesota as a Black person, your experience is undeniably Black because the people living in your same zip code look just like you. As a Black girl who grew up in Connecticut, I concur, that's real. That is the experience. Also, if you casually talk to people who knew him personally, regardless of what was said by him in interviews or who represented his parents on film, Prince was what Jill Jones said in one interview, "a brotha."

Yes, he has played the passing game. We can also judge the hues of the women on his arm, but if we are going to go down the rabbit hole of quantifying one's Blackness, we have to get really honest about the politics of race in the music business and the culture of white supremacy that has been a battering ram against the psyche of Black people since our first ancestors were brought here 400 years ago. But the evidence of his Blackness was laced in his lyrics.

No matter what he had to say publicly, know that finessing the media is a game we all play in this business. Prince's music always spoke the truth, regardless of who delivered that truth for him: Prince, Alexander Nevermind, Camille, Jamie Starr, O(+>, Tora Tora and a dozen or so other personalities he donned over a nearly 40 year career. He was a Gemini to his core, two people, and we are learning there was the Prince we saw and the one no one saw, no matter how close they were. Everyone who knew him knew a different Prince.

In another interview reprinted in Time Magazine's 2016 Prince Tribute, Jill Jones said Prince had a Madonna-whore complex. This can be said for most men — at least in my experience, it has been true. Still, it's a very astute observation from someone who knew him better than most. Society tends to socialize men about femininity as something that exists to serve their needs, teaching us all that men get to define the ways women behave or identify according to personal tastes. Although there were many ways in which he was a free spirit, we have to be realistic and recognize that Prince, too, grew up in the world and could not escape the influences that abound. Nor could he be spared the type of indoctrination we are all subject to when it comes to gender identity and sexuality, especially when the latter two are racialized. These are often distorted when it comes to people of color and just as sexuality can be racialized, race is often sexualized.

Hindsight being wise, this is probably something many others have come to see over the last three years as they reflect on their interactions with him. There is a balance in there, somewhere, most of us just haven't found it yet. Whether or not Prince was able to strike that same balance successfully in his personal life is best left to be said by those who shared a personal life with him. Unfortunately, the desire to rewrite history so that it is flattering to you is not just something journalists want to do, but at times, those whom we've loved and who loved us will be tempted to as well.

As "we march" into this sacred season for those of us who are of faith and whom are also of the faith of Prince, we are also searching for balance and trying to make sense of the (profane) senselessness that is year three of his absence while looking for the (profound) lessons to be learned in how he lived his life and the painful truths there are to be learned about his death. But learn them, no matter how painful. Be cool, be funky, be wild and just celebrate the gift that he was for the time we had him. And when you find yourself in that place where he has you thinking in ways you never imagined, you've arrived at your destination, the place, musically, he always wanted to bring you to.

We celebrate Easter as the third day, when Jesus rose from the grave and ascended into the heavens. This is the third year since we lost Prince. It is hard carrying the pain of losing someone. We fight like hell to hold onto them. You have to ask yourself, "Are you holding onto them or are you holding onto the pain of losing them?"

This season is about letting go and believing that there's someone up above who is watching over our very souls. If you understand that, you know he is one funky little man. Maybe it is time we let the pain of losing him go, just a little. How profound would that be?

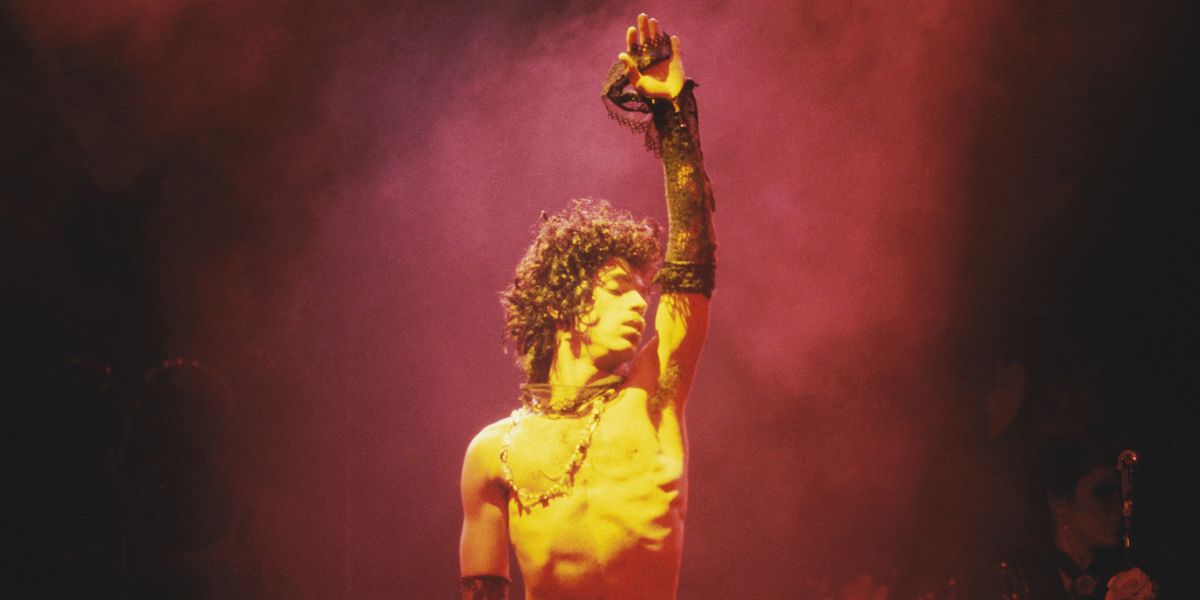

Photo via Getty