Nightlife

Nightlife Legend Jim Fouratt Talks What Really Happened at Stonewall and Birthing Danceteria

07 April 2017

How's this for credits? Jim Fouratt has been a record executive, magazine editor, activist, film critic, and club entrepreneur, and he has even run for office. Acknowledging him as someone who's been a longtime creator, observer, and survivor, I called Jim for a history-drenched chat.

Hello, Jim. Let's start with the famed Stonewall rebellion of 1969, which came to define the modern gay movement. You have said that the presence of people of color at the rebellion is actually overstated.

Yes, I have said that, and there is a reason for me saying it. The way the Mafia, quote unquote, meaning organized crime, operated gay bars in the '60s and '70s was they had gay bars for people of color, mostly black gay people, but they were on 42nd Street and up in Harlem. In the Village--except for Keller's, which was specifically aimed at black gay people and rough trade—most of all the other gay bars in the '60s had very little mix of races. Of course, if you were a great beauty, no matter what color you were, you got in, but people of color weren't catered to. It's called racism. There was systematic racism. The problem I have is people trying to claim to be a part of something which they weren't. The whole question of both drag queens and people of color at Stonewall…

The Stonewall Inn was pretty well known as a place where closeted gay men, usually married men, went to make arrangements with younger gay men, and the younger men, for the most part, were certainly not drag queens. There was drug dealing and prostitution, so all these romantic ideas of what happened did not happen. It was not a bar I liked particularly. It did not have a good dance floor. The jukebox was like every jukebox in every Mafia bar in the city. It was not a specialty jukebox. I know this goes against myth, but putting a straight '60s template on what happened that night robs us of who we are and what actually did happen, which changed how lesbians and gays saw themselves. By no definition can what happened that night be called a riot. I've been in riots. They're very scary events—people out of control, looting and robbing, the breaking of windows and turning over of cars. That did not happen the first night of Stonewall. The Stonewall rebellion actually started out quite small. I happened to be coming home from my job at Columbia Records. I saw a sole police car outside of the Stonewall Inn. I was out in the New Left movement and the anti-war movement and there was an incredible amount of homophobia—in the old and new left. Like a good '60s radical, I went to see why that car was there. There might have been 20 people around—this was 10:30 at night. The door opens and out comes one police officer and a "passing woman"—a biological female dressed in men's clothing. I'm using the language of that day. "Bulldyke" was said if you wanted to put somebody down, while "passing" was a nice term. She had been handcuffed. By now, about 40 or 50 people had gathered. It was a Saturday night, warm, June, summer. Her bulky body started rocking the police car. To the cheers of the crowd gathering, one of the doors had not been locked. She got out, and as bulky as she was and acted, she had small female wrists and was able to get out of her handcuffs. Given the cheering, she stepped up to play her passing woman masculine butch dyke role. She started throwing herself against the police car and it started to tilt almost to turning over, and that was a flashpoint. Something happened in that crowd that I cannot describe verbally. That's why I call it a rebellion--they finally rebelled against their internal and external homophobia and repression and started to cheer. A police officer came out, to look at the crowd and went back inside. From what I understand, he called for reinforcement. Within 10 minutes, a number of police cars arrived. Contrary to what David Carter's Stonewall book describes, there were very few arrests. The only arrest I actually saw was a folk singer, Dave van Ronk. He was drunk and saying "What's going on here?" The cops said, "Get away," but he was persistent.

Thanks for the insight. Let's move on to your achievements in nightlife. You were instrumental in the legendary club Danceteria, which started in 1979, along with your then-business partner Rudolf Pieper. That club is where new music was broken, along with art and videos. It was a veritable culture emporium. Did you realize how magical it was?

You've known me a long time and our paths have crossed many times. My political work I've always seen as cultural work. I've been an actor and appeared in plays and at Caffe Cino. It was around that period of time that was very fertile in terms of alternative culture. I took over the dead disco Hurrah and made it very successful and that became the template I was working on as to how to maximize culture--high art, low art, and politics. When I had the opportunity to take over the space on 37th Street (the first Danceteria), which had been an after-hours gay black bar, where there had been many killings, I wanted to make a club similar to what had happened at Hurrah. I hired people who had worked for me, including security people who looked like the people I wanted to come. People who were incredible but unemployable, I gave them jobs. Keith Haring was a busboy, and so was [artist] David Wojnarowicz. Keith did art on the walls the first three months. It all predates MTV, AIDS, and crack cocaine because what happened to nightlife was MTV changed how people went about seeing live music--they wanted to see the bands they just saw on TV, usually a British band which was incapable of recreating the sound live because they hadn't played that much.

When you opened the second Danceteria (on 21st Street), video became more prevalent.

Yes, video art began to come out of Downtown. I hired Kit Fitzgerald and John Sanborn, who were part of that scene, and I asked them to curate. It became the people who are now at the museum level of collection. The thing about New York that was different from L.A. and San Francisco is we all live for the most part in small apartments, and we all go out for social interaction, hoping to get laid essentially, straight or gay. I wanted to create an environment that was safe—no fights—and that was the purpose of the door policy. I also wanted a mixed club, and anyone was welcome who could behave in that mode. We started branching out in different kinds of programs—Word-Beat (spoken word) with Patti Smith and John Giorno, and Serious Fun (with people like Philip Glass and Diamanda Galas). The first club was three floors, and the second club was three floors and a roof. Once you were in, you had the option to do what you wanted to do. We did a whole lot of benefits--this is where the political stuff came in. With my door people—Haoui Montaug and Aleph Ashline—gay boys and women got in without any hassle. With straight guys, the test was they'd have to wait a few minutes and see if they didn't get hostile. We never had a rape or a fight, or any of those kinds of things that happened in those kinds of clubs. It took a long time for John Argento to destroy that template. Many people went to Danceteria 3 after I'd been locked out by Rudolf and Argento. Those people didn't know about the backroom drama going on, they just wanted to have a good time. I never criticized anyone if they had a good time under those circumstances.

The music at Danceteria was thrillingly good.

The DJs were the heart and soul of the club. The dance music that Mark Kamins and Sean Cassette did at the first Danceteria! I discovered Sean at the Mudd Club; he's the one who introduced me to Rudolf. And Mark was recommended to me by Nancy Jeffries, who did A&R at RCA. Mark played every club I ever had. Sean stopped playing after the first Danceteria. Chi Chi Valenti was a bartender. These people needed jobs, and the bottom line is I was able to give people jobs. I had an open call like a Broadway show, and I was very proud of the staff.

Tell me something really offbeat that happened at the club.

At Danceteria 1, the boys in the backroom found a loophole where people would buy a ticket for liquor, and we'd stay open very late.

The mob guys?

Yes. You couldn't do a club at that time that didn't have organized crime involved. They'd apply for these one-day permits over and over again. It was quasi legal, but it was an abuse of the law. The headliner would play two shows and the opening act would play the middle show and the last show would go on around four in the morning, so people could come from the other clubs and see that artist. If I was the owner of the Underground [a rival club], I'd be pissed that I couldn't do that. At the second Danceteria, the late show would be at three in the morning.

What's your take on then and now?

It's a different time. We don't have those kinds of clubs I'm aware of anymore. It wasn't as hard to survive in New York in the late '70s and '80s as now, though you still had to pay the rents.

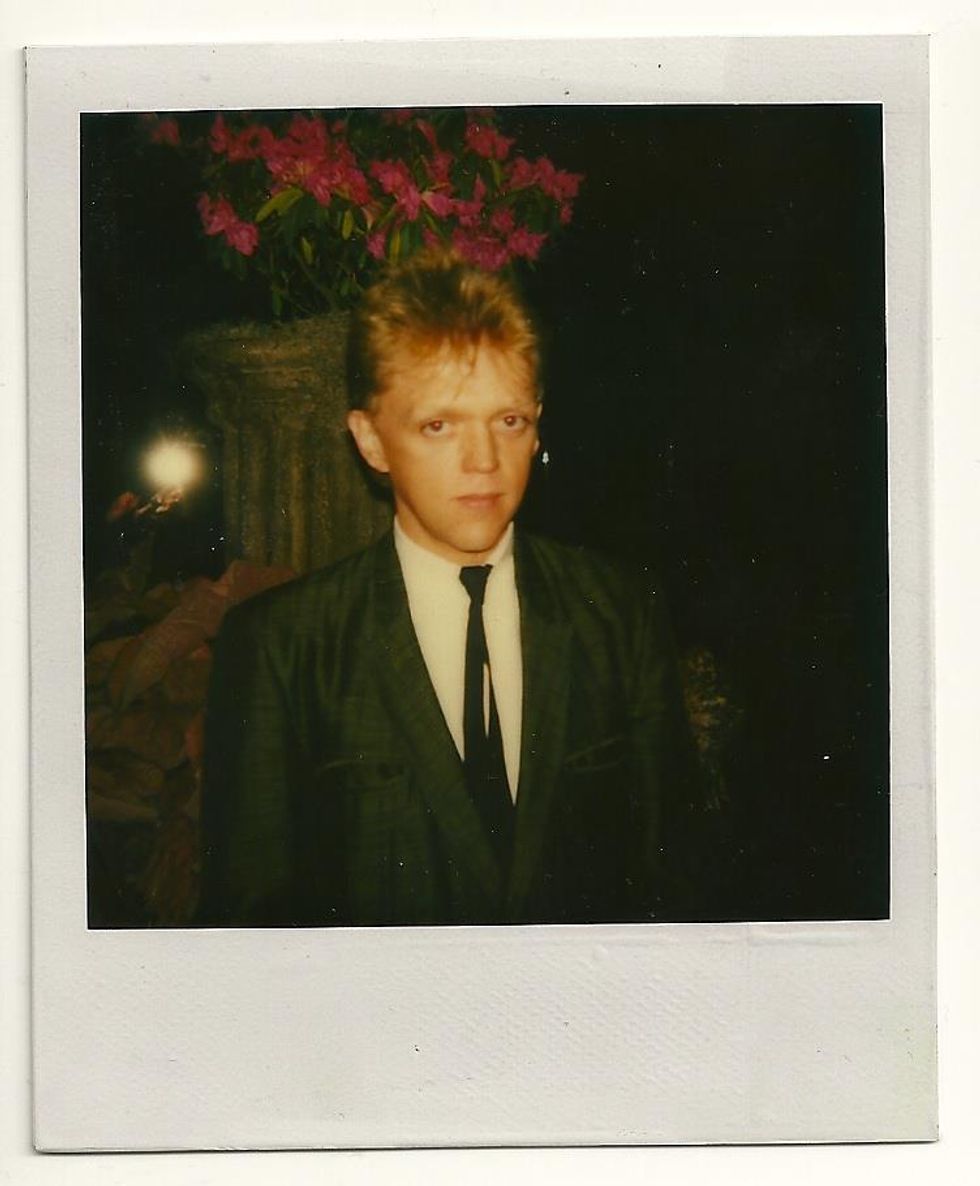

Splash image: Photo by Ebet Roberts/Redferns