This interview originally appeared in a 1997 issue of PAPER Magazine.

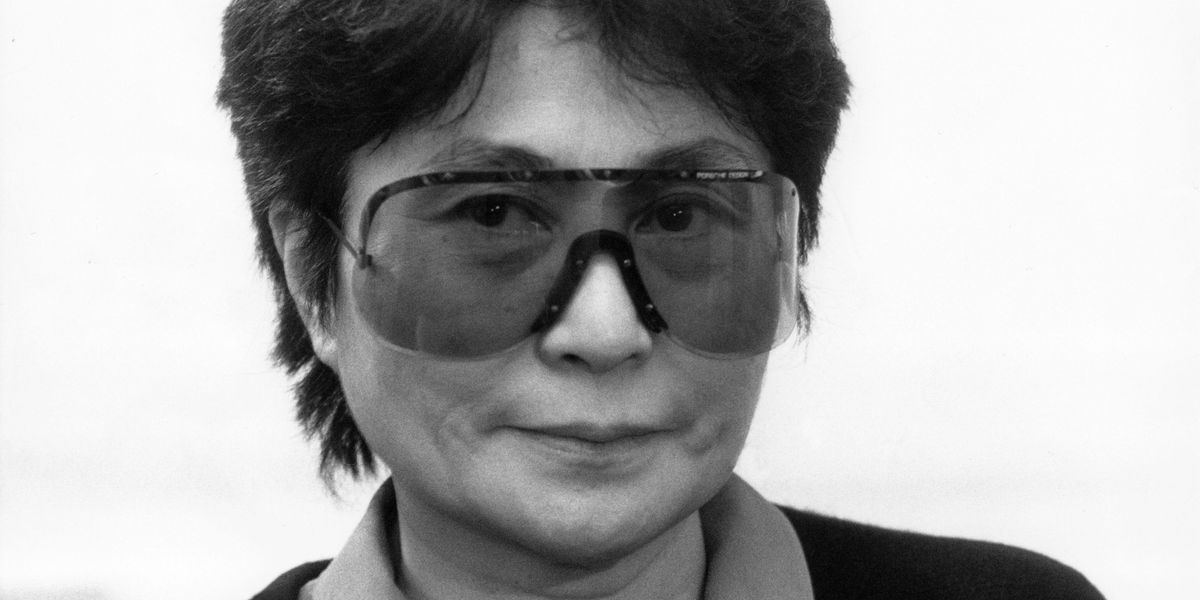

Yoko Ono tells me: "When I sat down and started talking to you, I felt more and more that you were my mirror." As a mirror I may reflect an empathic understanding of Ono's own reality, yet there remains so much that she has seen, known and experienced that I can only imagine.

As a gifted artist — an Asian woman working and producing at a time when there were no cultural studies, no focus on border-crossing, no Benetton ads, no celebration of multiculturalism and definitely no accepted fascination with eating the other — she was on the front lines, a vanguard bohemian diva inventing herself. Although I have followed Ono's career for a long time, I do not recall any reviews written by women of color about her work.

Before seeing Yoko Ono, I do my own walk down memory lane, remembering the first time I saw her face-striking, serene and strong. I listen to songs she has composed from her new 11-CD collection (available on Rykodisc). I listen as intently now as I listened years ago, hearing a continuum connecting this body of work with new music by contemporary younger artists both female and male, from the Cocteau Twins to the artist formerly known as Prince. Ono was so before her time.

Her artistic career has never been fully assessed on its own terms. For way too long it was subsumed by mainstream culture's focus on her husband, John Lennon. It's a positive sign of the times that Yoko Ono can take center stage. The world that was not ready for her years ago is ready to receive her now.

bell hooks: As a young artist trying to find my way, I looked to the work of Yoko Ono as a guiding light. As I thought about you, the first thing I wanted to know was here you were, this beautiful baby in Japan — what led you to experimental work

Yoko Ono: I think there was a rebel in me always, and without that I wouldn't have survived. Without that I would have probably become somebody who may have survived physically, but not spiritually or mentally.

bh: I remember the first picture I saw of you. You had this big-

YO: Face-

"I think there was a rebel in me always, and without that I wouldn't have survived."

bh: This big, broad face. I think part of what made you striking is that you have this very strong look, which I think is against notions of femininity.

YO: Exactly. Even my mother said that when I was younger: "You are a handsome woman, but you're not pretty; pretty girls don't have those big bones" — you know, big cheekbones like I have. And it's much better to be a pretty girl than a handsome person. You could almost pass as a guy. What's wrong with that? Is there something wrong with me? I look at people straight, I talk straight and all that is kind of against the ideals of feminine women, I think.

bh: Absolutely. People used to think of Yoko-Ono-meets-music as screeching, but to me you are the precursor of the kinds of women's groups that people are loving today, from the B-52's to the Cocteau Twins. I hear them and I think, "Yoko Ono."

YO: Well, you see, I'm looking at my life, and there were times when I was really frightened because the whole world was attacking me and throwing hatred at me in writings. It was a bit scary, and also I didn't understand why they were so angry with me for me just being myself. But I went through that, and now when I look back I think it was a kind of lesson that all of us had to learn together. Part of it was very hard for the fans, too — suddenly this woman, who is not even a pretty blonde white woman or something, was sitting next to their hero and occupying a kind of equal space.

"...suddenly this woman, who is not even a pretty blonde white woman or something, was sitting next to their hero and occupying a kind of equal space."

bh: Well, which fans? If I had been writing all the copy, I would have been talking about you and about what this meant to me and to other women of color to see you centralized.

YO: I think some people were annoyed by the fact that a woman of color was sitting next to this white hero, but then they got used to me in a way. And then the next time they saw a woman of color, they would have a different context.

bh: Exactly. Get them off the ground.

YO: I feel like maybe that's what I was used for in a way. In the big picture I feel almost that was my fate.

bh: I want to ask you about the period of silence you went through, because I was very disturbed. From my distance I thought, She's having this long period of silence. She's entered this corporate world. Have we lost her? Can you talk about that?

YO: I was writing, but not as much to think, Well, I have enough to make a record. I think the pain of losing John was catching up. Right after John's passing, it was almost like I was still in this mood-we-have-to-fight- together kind of mood — and there was so much I had to do. And there was a delayed reaction, a very, very deep depression that I was in. And then, well, this is something the world doesn't have to know. I tuned into the pain of widows because it's not just losing your partner and the pain of it, but many people specialize in living off widows and attacking widows and thereby gaining, and it just kind of accumulated. I was at the point where I was really trying to use all my efforts to try to survive, and therefore the silence. And I think I have survived.

"I was at the point where I was really trying to use all my efforts to try to survive, and therefore the silence. And I think I have survived."

bh: You absolutely not only have survived, but triumphantly. So what is it like to be this totally gorgeous woman over 50 playing your music in a nightclub with the latex-wearing 20-year-olds?

YO: [Laughs.] I think the reason why I keep myself healthy is that I keep trying to communicate and express myself. And I think by communicating and expressing myself I'm part of this big thing — a big entity called the human race — and that's what keeps me going.

bh: I feel like you have dealt with so much of the hostility with compassion, and it seems like your vision of love has really come full circle. Could you talk some about that?

YO: Let me tell you about my anger. I mean, when John passed away, there was an incredible sadness and fear and shock and all that, but also I was angry, too, of course — [there was] a big there. And I felt if I drown myself in anger, I'm going to kill myself — the anger is going to kill me — and I can't be in that space. I just had to tell myself how to transform all the energy of anger, of sadness, into something that's more positive. I had to do that for my own good, and that was another kind of insight I had at the time; being angry isn't destroying others, it's destroying yourself. And being sad, too, doesn't destroy others, it destroys you.

"...being angry isn't destroying others, it's destroying yourself. And being sad, too, doesn't destroy others, it destroys you."

bh: What's it like now collaborating with Sean [Lennon] as a musician?

YO: Oh, It's great. That was one of the most beautiful experiences I was given in the past several years.

bh: So let's go back to how you feel when you're at the Knitting Factory and you're in the world of people who are largely under 30 and you are the diva delivering the hip night. What does that make you feel like?

YO: It was great. I think I know the secret to health — I was going to say success, but health is the most important success we can attain: The secret of health is to pick up something that makes your heart dance. You're going to have to physically dance and everything. And I really felt that when I was onstage and doing the thing with Sean — just kind of communicating with a small audience...

"The secret of health is to pick up something that makes your heart dance."

bh: Well, it's interesting, because Sufi mystics talk about dancing in a circle of love, and in so many ways your life has been a circle: you started out in Carnegie Hall recital hall performing for a small audience, and here you are now, back with a small audience being ever creative. I think that's part of the dance. It's a dance of joy. Where are the secrets of joy in Yoko Ono's life now?

YO: It's that little dance of my heart that I listen to.

bh: Well, I am so happy to have had the privilege of dancing here with you today and I thank you. So do you have a last little word you want to say?

YO: Keep dancing.

Photo via Getty

From Your Site Articles