There've been many attempts to peer into the lives of America's self-exiled. Labeled crust or gutter or street punks, or simply travelers (or depending on your politics, hobos), I mean the large network of nomadic Americans who have made the deliberate choice to live without addresses or incomes, outside capitalism, the work force, the nuclear family, and most rules of social conduct.

If you live in a large city — especially Seattle, San Francisco, Chicago, Asheville, San Diego or New Orleans — you've seen them. As the myths go, they panhandle and perform in parks, hitchhike or ride rails with the weather, give themselves new names and histories, live in squats or on the streets, often adjacent to musical scenes and activist communities. These myths are reified and to some extent confirmed by films and documentaries like Crash Where You Land (a look at New Orleans' French quarter's homeless punks), Hunting Pignut (a fictional gutter punk adventure in Canada), and The Decline of Western Civilization III (the third in a trio of punk documentaries, exploring LA's crust scene).

Our fascination feels like a result of the wrench these people throw into the logic of our own lives. Most of us pour endless labor into the task of acquiring a Good, middle class life. The fantasy of skipping out on that project altogether (though these travelers are sometimes those who never had a good shot to begin with) and the equation of the comforts you sacrifice for the freedoms you gain, is equal parts intoxicating and terrifying.

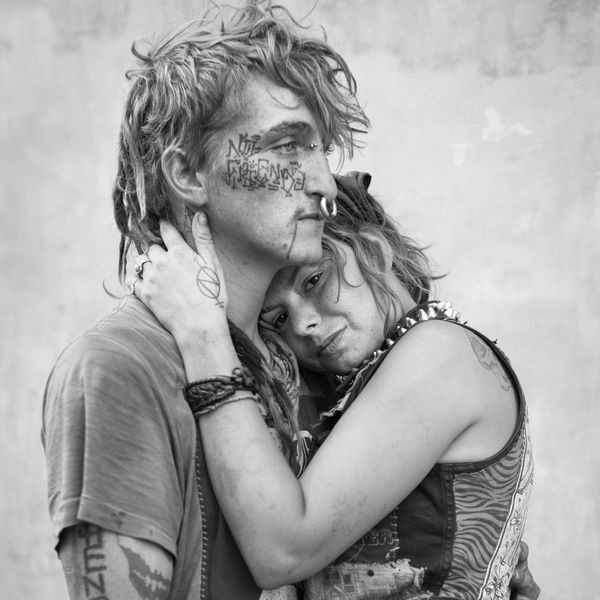

Michael Joseph, a Boston-based photographer, has spent years traveling around America getting to know members of this complex, transient community, learning about its history, language and codes of conduct. In a new exhibition at the Daniel Cooney Fine Art gallery in Chelsea titled "Lost and Found," Joseph explores its reality with a series of black and white portraits: individuals, couples, parents and children.

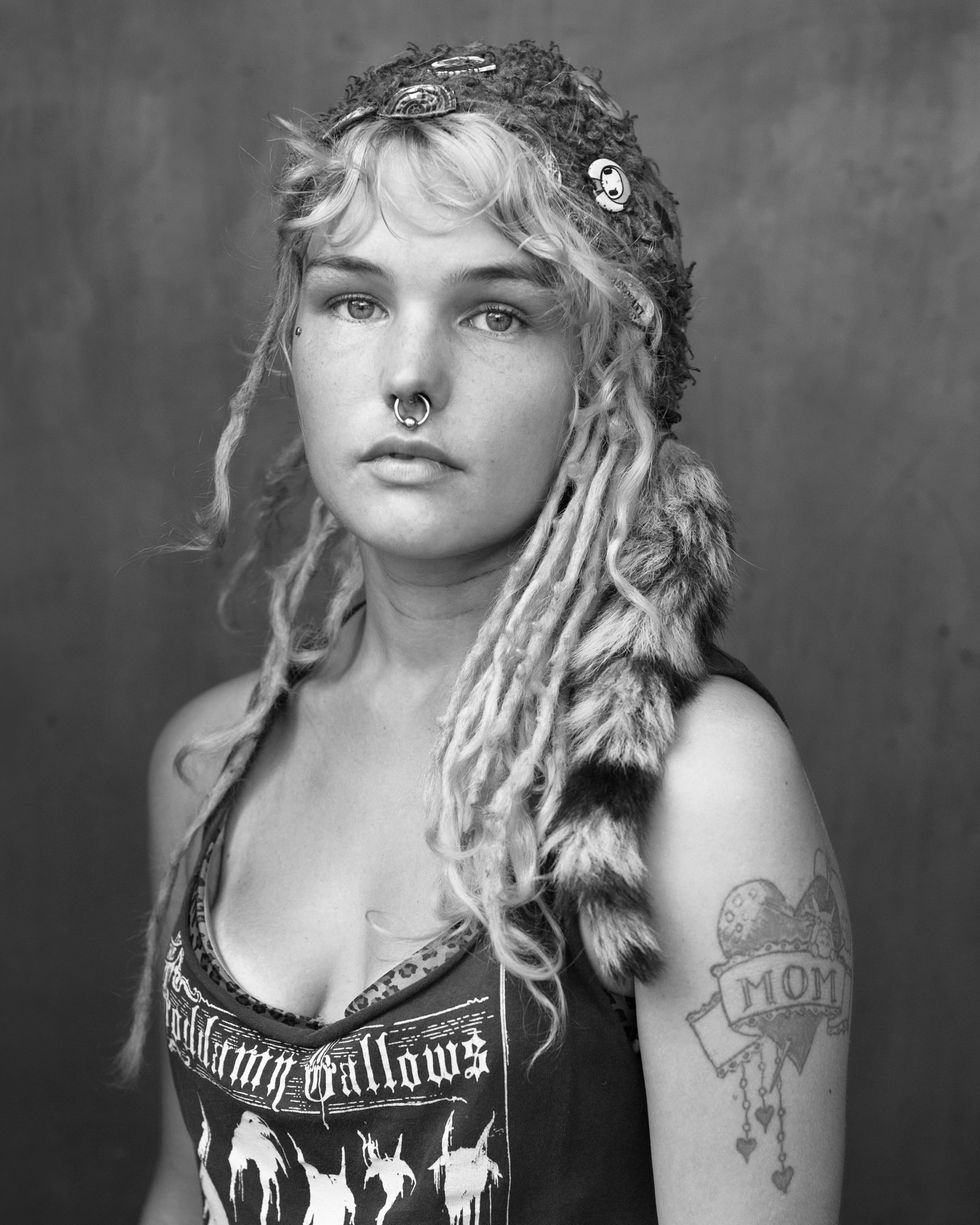

"Trey"

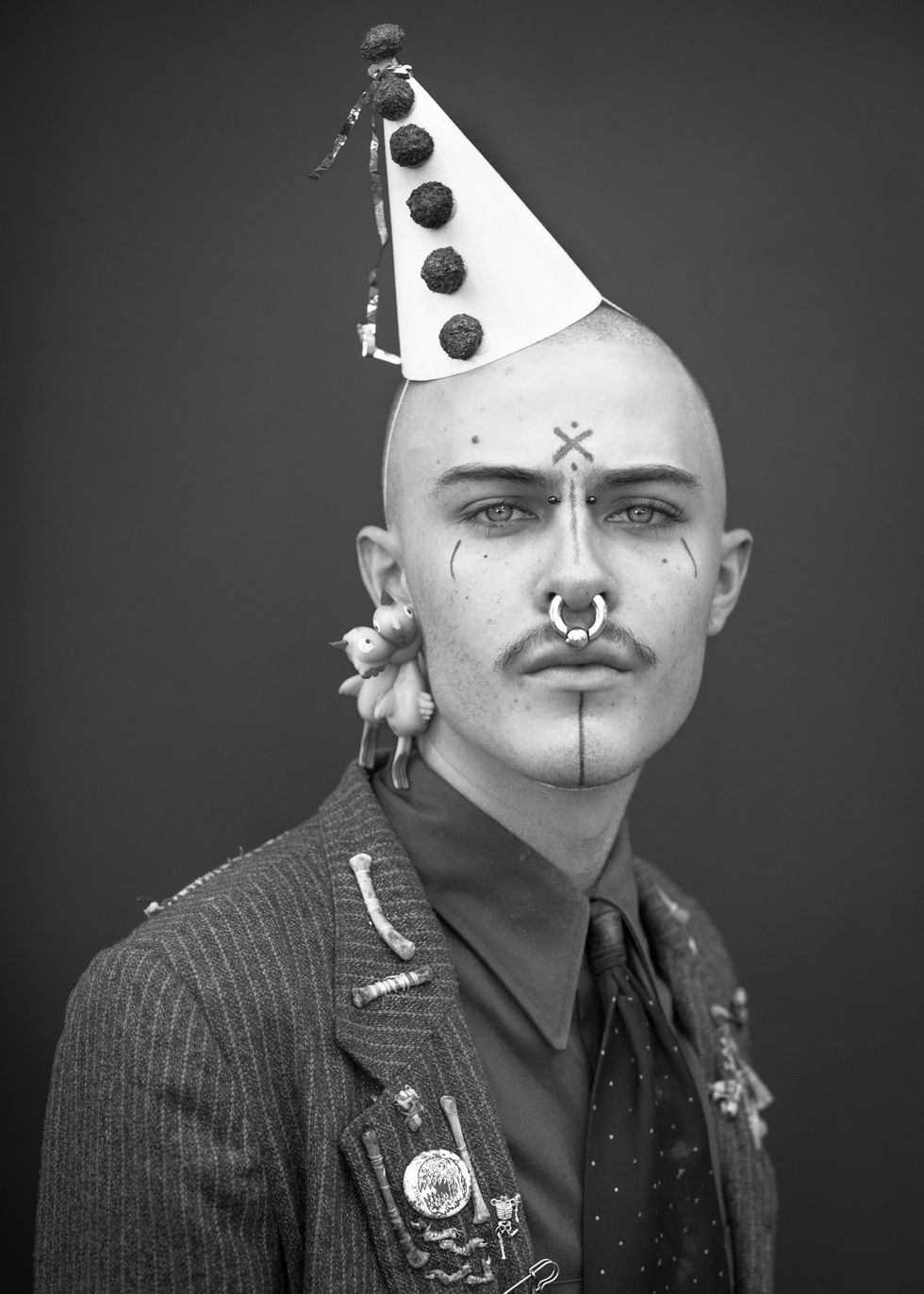

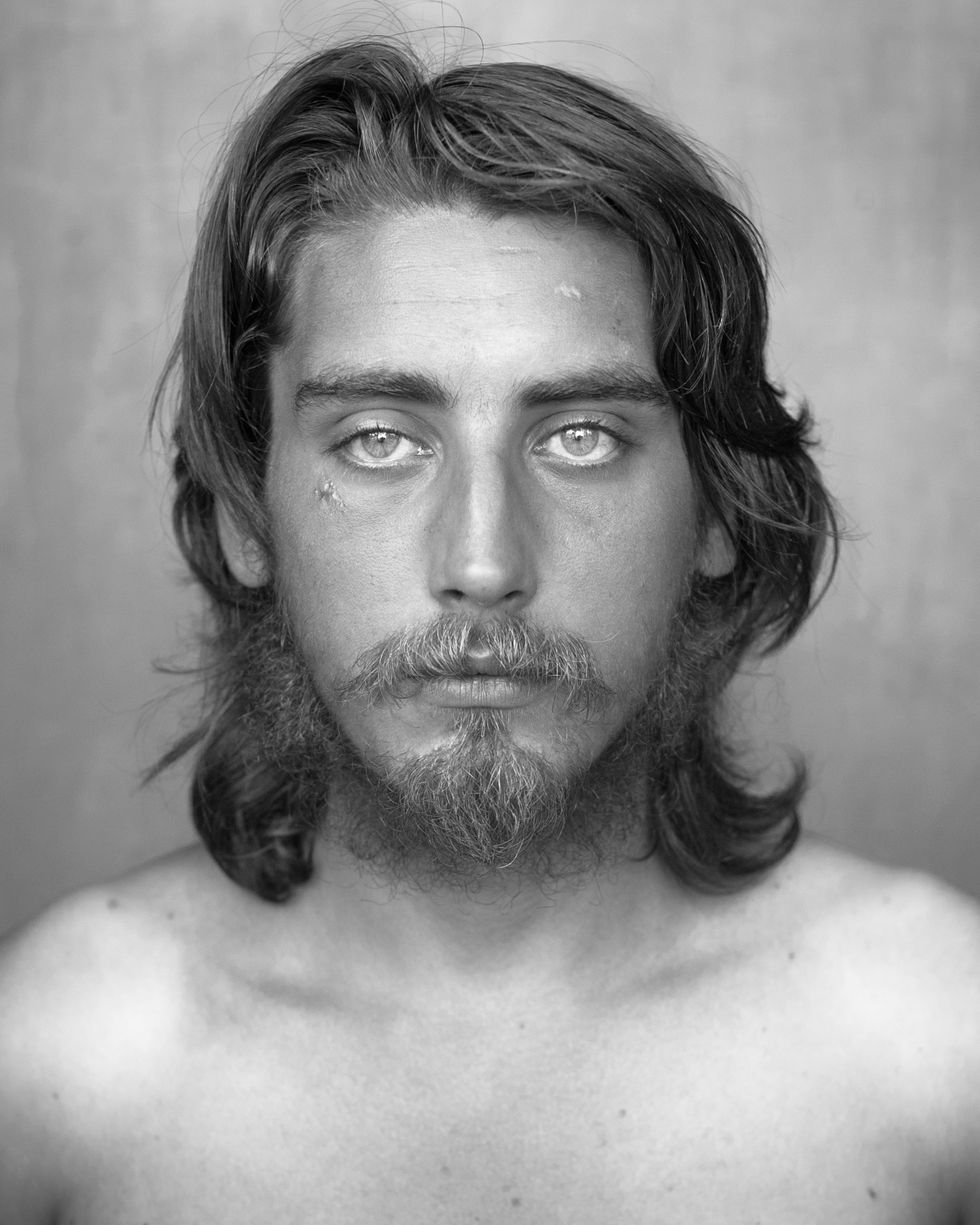

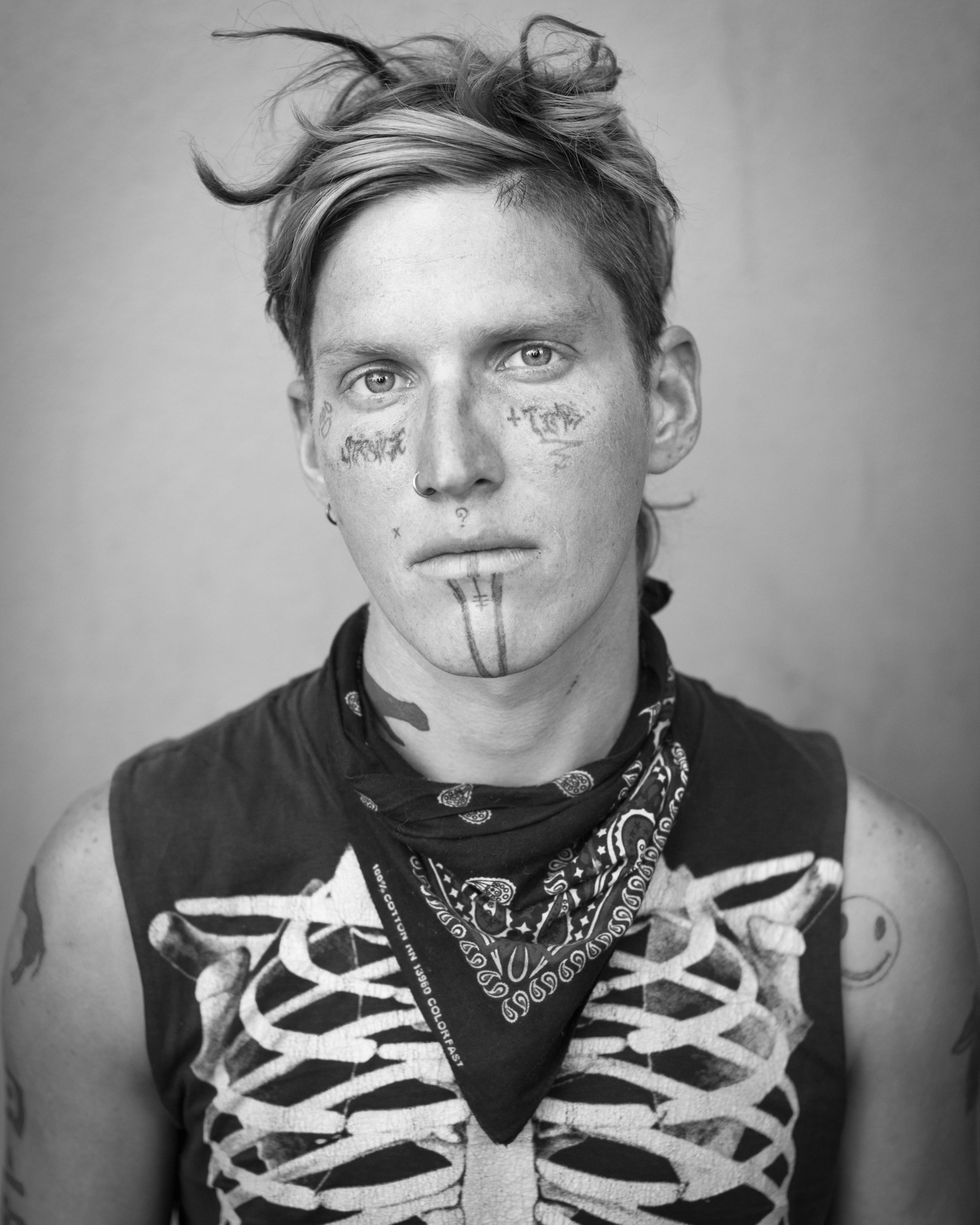

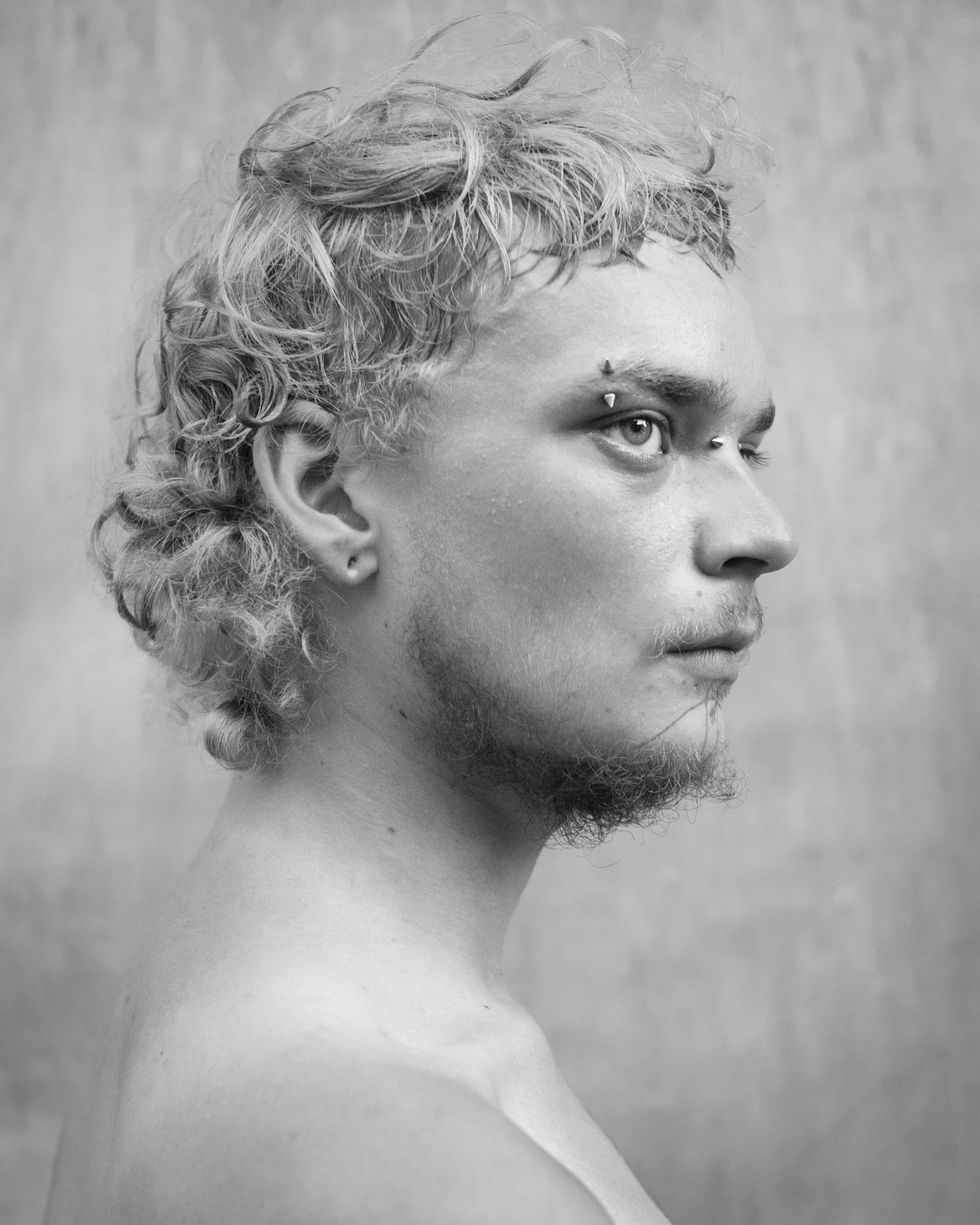

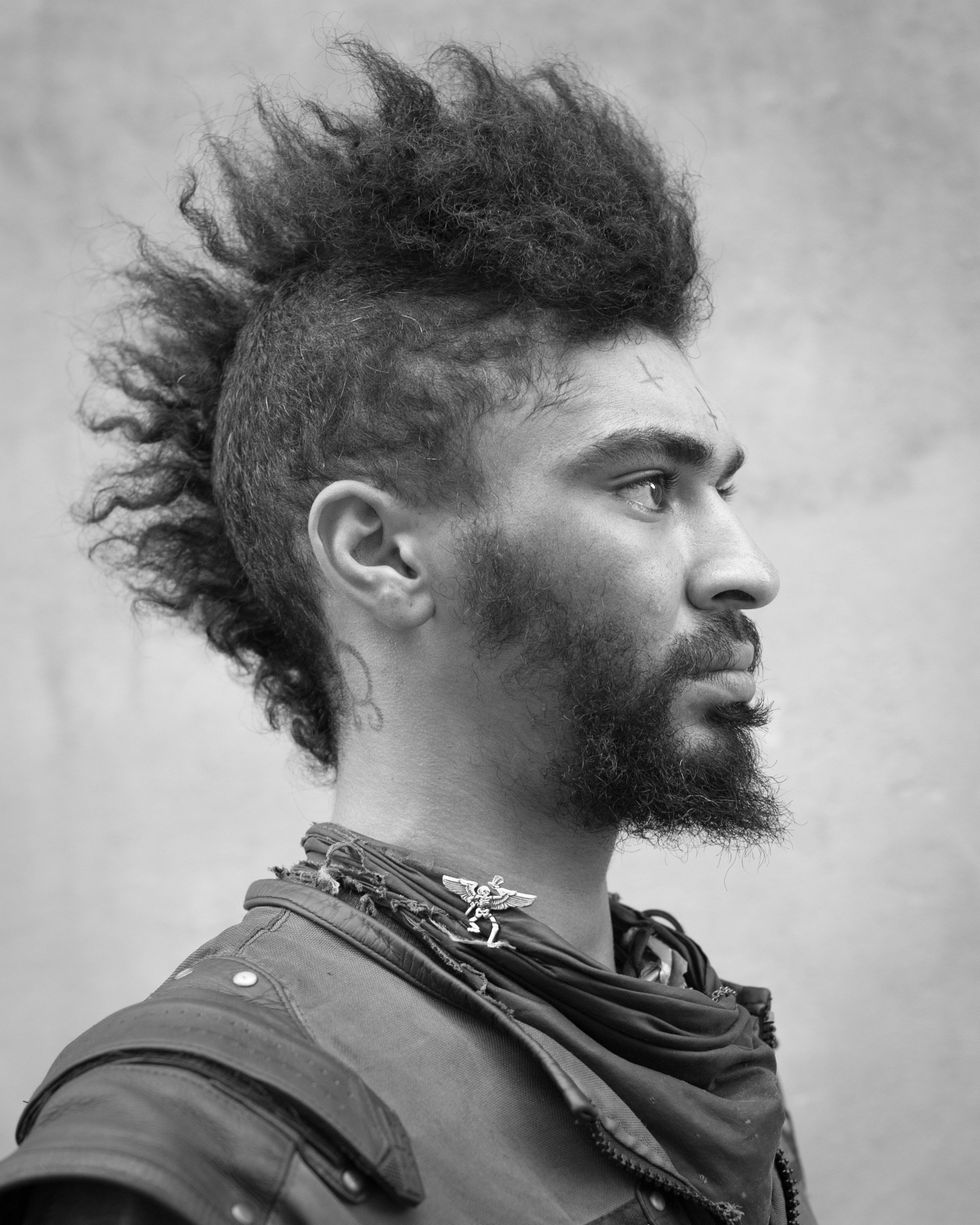

Rather than the blurry YouTube footage or dark polaroids typical of punk memorabilia, the photos are exhilaratingly detailed. The figures are rarely smiling but make unyielding eye contact with the camera. The close-ups allow the viewer to see beyond spectacle or curiosity, and admire the clues the photos offer about the subject's stories and journeys. One man's glasses balance on his nose without arms. Another's jacket is embroidered with what look like bird bones. A woman drapes her arm over her head to reveal a line drawing of New Jersey on her armpit. A tattoo on one subject's stomach reads, "Do not fear death, but the inadequate life." Anarchist and squatters rights motifs are common.

"Raskull"

The series insists upon beauty in the constellations of stick and pokes on arms and faces, and the layers of patchwork handmade clothes and jewelry rooted in "crust punk tradition and hobo history." This warmth of Joseph's shots and the agency in the punks gazes eschews the anthropological distance inherent to a photo series of homeless people hanging in a Chelsea gallery. The people appear neither overly romanticized, nor tragic. In a statement, Joseph points out that without context, they might just look like Bushwick's more rugged crowd, until closer study reveals bruises, dirt and scars, "clues of problems including physical abuse, substance abuse, lack of medical care, loss of friends and family." Although they're beautiful, the photos feel ultimately agnostic when it comes to passing judgement on the subjects' lifestyles. However, Joseph admits that he hopes to celebrate the "courage and freedom of lives spent on their own terms."

"Lost and Found" is on view at Daniel Cooney Fine Art until April 13.

Photos courtesy of Daniel Cooney Fine Art