Our culture's endless fascination with women and ideas surrounding womanhood has become crystal clear.

This largely stems from patriarchal desire to control and police women's narratives and needs. And whether dead or alive, the focus always remains on women's bodies. Society has long relied on "dead girls," from Britney Spears to Jon Benet Ramsey, to reinforce its expectations of women, and how they're supposed to exist among men. It's everywhere else in pop culture too, including on classic and contemporary TV shows, like Law and Order: SVU and How to Get Away With Murder.

Constant reiteration of gender norms for women, especially in the wake of the Trump administration, is nothing new. In fact, it's uniquely American. Who would we be without it? Author and pop culture writer Alice Bolin explores these points at length in her breakout book, Dead Girls: Essays on Surviving an American Obsession.

As scarier times approach for women, the current administration fuels it with greater restriction of women's rights, including the debate about Roe v. Wade rollbacks, and the recent Supreme Court appointment of pro-life Judge Brett Kavanaugh, despite multiple accusations of sexual assault against him. These changes have been alluded to in dystopian shows like Hulu's The Handmaid's Tale, which is perhaps a feminist flip of classic "dead girl" narratives.

Social observers have also noted that the fury of American women has motivated most of the anti-Trump resistance since his 2016 election. We see a fantastical version of said fury in this year's politically charged remake of Dario Argento's 1977 camp horror classic, Suspiria, where Tilda Swinton leads a coven of matriarchal witches masquerading as an all-female dance academy.

"Dead girl" narratives are slowly being reclaimed, as a reflection of America's current political tension. But we couldn't help but wonder: as patriarchy continues to crumble, what might the opposite, a "dead boys" society, look like? We have an idea, based on emblematic pop culture figures, ranging from living (emo rock stars like Gerard Way and Davey Havok) to dead pioneers (from Kurt Cobain to Lil Peep). But how are those men differently valued? In today's culture, where women are shamed until the very end — and even in the end — and men are revered, how would the world look if the focus of our centuries-long obsession was reversed?

PAPER caught up with Bolin to pose these questions, and the answers might surprise you.

As shown in your book, America is largely focused on what a "dead girls" society looks like, but what do you think a "dead boys" society would look like? There are some examples of what that could be: for example, this generation of rappers like Lil Peep — people who die of addiction hard and fast, and it's sort of that rock n' roll idea, like James Dean. There's a reassertion of masculinity that still venerates them, but when a woman dies in a similar way or goes missing, they don't become heroes.

Most murder victims are not women, most of them are men. When we talk about a dead girl culture we're talking about this fixation that's in the media that's not really necessarily reflected in reality. It's a narrative that controls women's behavior and teaches us fear to socialize us, but doesn't necessarily reflect the truth of crime and danger and who's really threatened. A lot of those male victims are from marginalized communities; often they're poor, Black or Latinx, and their deaths are not treated as mysteries, and their bodies are considered disposable. That's one thing I wanted to think about — really, we do live in a dead boy culture as much as we live in a dead girl culture. In unpacking those dead girl narratives, part of it is seeing who are honoring real victims, and looking at the truth of crime extricated from all of these narratives that are so wrapped up in myth.

"A lot of those male victims are from marginalized communities; often they're poor, Black or Latinx, and their deaths are not treated as mysteries, and their bodies are considered disposable."

There's obviously nothing wrong with being interested in mystery, because we have such cultural reverence on an entertainment level for the mystery of murder, as it specifically affects women, for example. The nature of crime itself really centers on male victims more than anyone.

That's part of what the allure of these female victims is. You have this "you're the outlier" attitude; women are protected in this place. It's so interesting to think about these dead boy "heroes," because it wasn't exactly what I was thinking of but it's very true in the ways that men who die of suicide or addiction are treated so differently than women who do. They definitely have an instant, sanctifying [posthumous air]. What I was thinking about was Sylvia Plath, and how her suicide is almost always mentioned when people talk about her, but another poet, John Berryman who also died of suicide and who was writing at the same time, it's always his work. They talk about his suicide very rarely; it's not the center of his story when it's re-told.

We internalize those things too, and that's how these stories get perpetuated, which you definitely touched on in Dead Girls.

There are so many contradictions. There isn't this mass-consciousness of unpacking where it all comes from, when more and more dead girl shows can and do exist. News reports often frame real-life dead girls in this elusive, protected, mysterious light while also teasing out all the details of her personal life.

If we did live in a culture where dead boys was the "thing," how do you think the world would be?

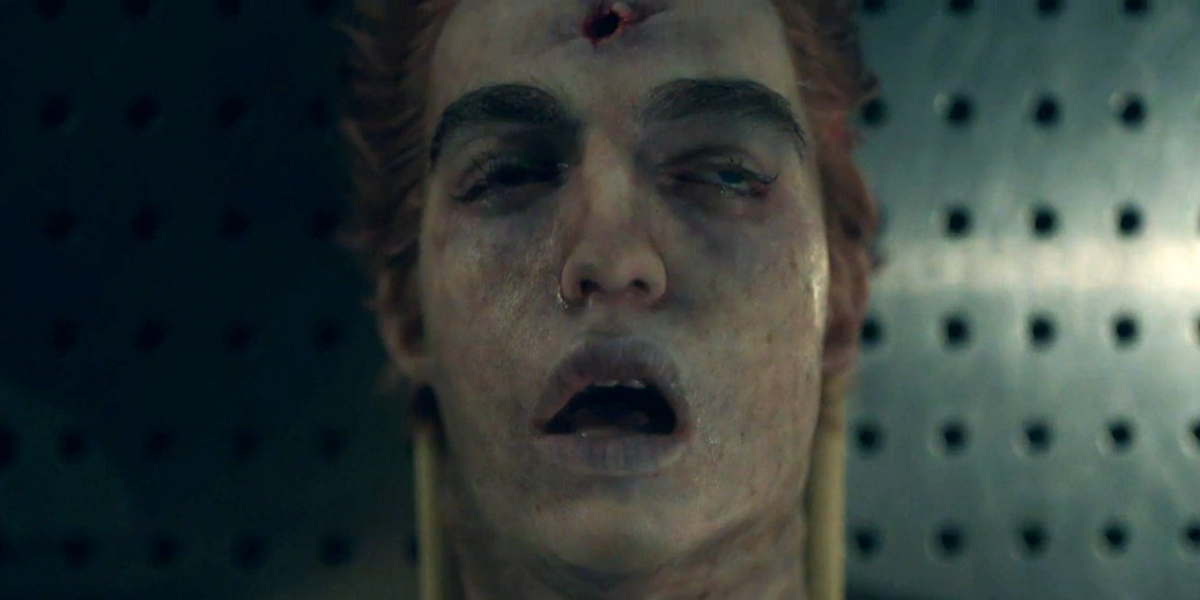

If you look at the examples we have now, it becomes pretty clear that when dead boys are portrayed in the media now, we give a lot more credence to who they were in life — their backstories, where their death isn't the start of the story. Of course there are exceptions; Riverdale is the one everyone points me to as a dead boy story. I don't want to be essentialist, where if the script were flipped, maybe it would be similar. Maybe we would start fetishizing these boys' bodies and taking out this anger and confusion on innocent young victims. I don't think that necessarily has to do with gender, I think that has to do with the narratives we've been given, the stories we've heard over and over again and these patterns we get into.

Related | Sandra Oh Talks Killing Eve

Are there any other examples you can think of?

The other example I was thinking about was Killing Eve — I think as this dead man's show, it's really interesting that almost all of the victims are older men. It is very consciously flipping the script, and I think there's something really disturbing in the way that show is received, where people were finding it really titillating — the fact that this beautiful woman was killing these men. There was even this really overt BDSM theme. When I watched it, I found it really scary and disturbing, and I'm sure a lot of other people did too, but the way it was talked about was horrifying — this person is evil. The fact that it's this female killer gave it an element of fantasy, and really sexual fantasy at that.

I'm a big fan of the Investigation Discovery channel's programming dedicated to murder, and so many shows center on female killers. It has shows like Deadly Women, where some of the scripted language is inherently misogynistic. These women are also framed as antiheroes in some ways, but also in the vein of "they were sex-crazed demons who did what they had to do to get their way."

Exactly, they're like freaks of nature, these black widows. There's something, especially the idea of them being so avaricious and sexually manipulative, that's so classic [misogyny]. I love Snapped too, but at first it was about battered women who freak out, or snap, and kill their husbands. Then it became this misogynistic thing, whatever the dynamics were to begin with. They start as interesting [people], or intelligent, or charismatic, where women's charisma always boils down to sex, quite often.

That's all they can offer, apparently. Except in cases like Aileen Wuornos, because our generation is framing her in a feminist narrative.

Sort of like a folk-hero!

The focus is on her vigilantism, and I wonder how much that has to do with Aileen's appearance — the way the public perceived her.

And even her being queer, to an extent. That to me is so dangerous. I know I'm a prude in certain ways, but it's the danger of that seductive narrative, where it's not good to murder people, ultimately it's very bad. We shouldn't really be glorifying this violence even if we can sympathize with who the murderer was. I feel like it's just a step away from the people who have Jeffrey Dahmer as their profile picture [on social media], where we think of serial killers as these camp figures. That really enables a lot of very banal violence.

What do you think is the difference between dead girl stories and those of dead boys?

[I see it as] the trope of the body in the library — you know, it's in Agatha Christie, Dorothy Phaire, those old golden age of mystery types of things — and it's considered this very pure mystery where you find a man with no identification in a room in some mansion and nobody knows who they are, so you're solving the mystery both of "who killed him?" and also "who is he?" There's no sexual obsession with his body, he's not some haunting figure, he's a purely anonymous mystery. I think it's exactly the opposite of a dead girl, who has all of these feelings wrapped up in her body, it's almost like this purely mathematical problem.

In death, male figures become almost saintly in their silence.

Right, their silence is first pure, and then beautiful. Even with Brandon Teena and Matthew Shepard, these victims of hate-violence because of their queer identities — not to make a one-to-one comparison because those people have been rightfully used to show the pervasiveness of violence against queer people — but that in the way those stories are told, it's very admirable in the ways they are humanized and shown as complicated. Those do seem like dead boys stories to me, though.

Unlike dead girl stories, often tainted by misogyny, with men and boys, I feel like it's treated the same in the sense that when they're alive, they're upheld as either a rebel or a hero, and when they're dead they're a rebel or a hero.

The dead girl story is bad for women, but it's also bad for men and male victims. I think that is the truth, for example, of male victims of sexual assault. In our focus of the ways how women are not believed when they're victims, we don't think about the ways men are also not believed and encouraged to not speak up. I think those tropes and those narratives are very damaging in lots of different ways, for lots of different kinds of people. The ways in which we live in a dead boy story and in which men are expected to accept violence are different than the ways that women are, but they still exist. Our not telling those stories means that we don't see it.

"The dead girl story is bad for women, but it's also bad for men and male victims. I think that is the truth, for example, of male victims of sexual assault [...] we don't think about the ways men are also not believed and encouraged to not speak up."

What do you think of how this crosses over into the horror genre? Horror is often based on the things that are the truest about us as humans, because they are the scariest to reckon with.

Often at the end of a horror movie, the girl is left and the killer is left, where the killer is a man who wears women's clothes, is obsessed with his mom, and has some sort of undecided masculinity. The girl is often the virgin, sort of a tomboy, has an undecided femininity. They collaborate to take down the homecoming king, and the cheerleader — these icons of appropriate masculinity and femininity. Ultimately, that's the enemy in the movies, and those stock characters tell us how we should be. Often, male victims in slashers are the football stars, and are killed really early.

It's almost like horror becomes this fantasy realm in which the patriarchy its removed, or stripped back.

Right, or maybe it's upset.

Or is disrupted.

It is sad that it lives in the fantasy realm because I wish that could be real. The disruption of patriarchy only happens through this more utopian vision — [the patriarchy can only be challenged] in a true horror situation.

"I think women are not interested in dead boy stories in the same way men are interested telling dead girl stories."

And then what's left standing somehow feels like emblems of queerness, which I'm here for, personally.

Me too! It's why I think horror is perennially popular and interesting, because of those [disruptive canons]. It's gender, but it's everything. That feeling of, this suburbia feels totally different, you know?

And in terms of a dead boys society, in order for that to be the supreme point of view for everyone, everything we know would have to be toppled. I think we would probably live in a more matriarchal society, for example.

That's interesting to think about, because I think women are not interested in dead boy stories in the same way men are interested telling dead girl stories. I think women are also interested in telling dead girl stories, because you're thinking, What does this mean for me? What does this say about me? What did it mean to grow up this way? You don't see men being interested in male victims, and you don't see women being interested in male victims, so I think that our whole cultural shift would have to change. You see women writing revenge stories, but never about the suffering of an innocent male victim.

In a matriarchal society, I don't think there would be dead boys or dead girls —this is all patriarchy.

It is! That's what I think too, that obsession of having a perfect victim, or with these murder stories is a reflection of the patriarchy, and really of an unfair society. When people have asked me, "Do you think we could live in a world without dead girl stories?" it's not exactly what I'm arguing for. To me, the only way that could happen is if you had a more fair and less violent society. Although I think it's interesting to flip the story, and to have a Killing Eve, I also think that's not necessarily the silver bullet. The solution isn't to just start telling dead boy stories, because even that, somehow, becomes a reflection of our obsession with dead girls at this point. I think [dead girl stories] are very reflective of the fears we live with as a society. You can't talk about one without talking about the other. That's a symptom of the conditioning we've all had our whole lives.

Photo courtesy of The CW (Riverdale)